Blowing a Storm in 1934

Floods cover a road in Mordialloc, 1934.

In November 1934 a devastating storm swept Port Phillip Bay bringing torrential rains, wild seas and, subsequently, massive floods to large sections of what is now the City of Kingston. It created great damage to property; boats were sunk, bathing boxes were swept out to sea, baths were damaged and lives were lost. The Argus reported that thirty four lives were lost statewide and 3000 people were left homeless. [1]

At Cavanagh Street, Cheltenham, in front of the House of Mercy, the flood was the biggest on record. The water was a huge lake reaching to the outbuildings of the home. [2] The iron roof of the Masonic Hall at Cheltenham was blown off, trees up-rooted and fences and hoardings blown down.

Along the foreshore piers, baths and bathing boxes were damaged. The Parkdale concrete bathing boxes were filled with many tons of sand and the doors were forced from their hinges. Between the McBean ramp at Charman Road, and the Mentone Pier more than half of the 146 bathing boxes were washed away, and both the Mordialloc and Mentone baths were seriously damaged. The Mordialloc baths, with the exception of the residential portion were almost totally destroyed.

Young boys quickly carted away the debris that was washed ashore, and adults seized the opportunity to gather the damaged timber from the piers and baths. The Chelsea News reported that people found by the police to be in possession of this timber would be prosecuted. [3]

Debris on the Mentone Beach. Courtesy of the Mordialloc & District Historical Society.

The Mordialloc Council had only recently spent £150 in repairs at the Mordialloc Baths and a new diving platform had been erected with funds from the Mordialloc Carnival Committee. The platform was washed ashore early in the tempest, before it reached its worst level. The Carnival trustees, at least initially, decided not to pay the bill for the construction of the platform, arguing the work was unsatisfactory as it was unable to survive a little pounding by a wild sea.

During the height of the storm Mr Taylor of Chute Street, Mordialloc , with the assistance of his family and the light from a torch, decided to herd his 300 ducks to shelter on Cr Wood’s property. They all arrived safely as the ducks were equally keen to reach safety and shelter from the pouring rain.

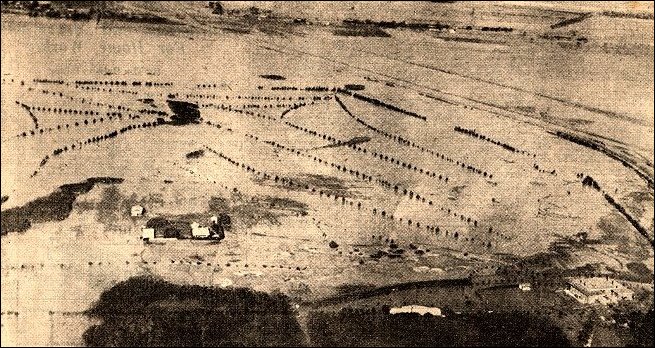

The major damage from the storm was experienced by people in Chelsea and Carrum, especially those living on portions of the Carrum Swamp. Although improvements had been made to the drainage of the swamp it was nowhere near adequate to cope with the massive amount of water pouring in from the Dandenong and Eumemmerring creeks. Early on Saturday morning the fire bell was rung in Chelsea to warn residents that the flood waters were rising. The Patterson River Golf Links were covered to a depth of several feet and at the Aspendale Race Course the water was so high that only the top of the judge’s box could be seen. [4] The Chelsea News reported the situation, “There was an immense sheet of water six miles long and three miles wide, with an average depth of twelve feet, the water rose so quickly that many families were forced to leave everything behind, many being rescued in their night clothes.” Women and children were housed in the Victory Theatre, Chelsea and the men in the tennis pavilion and in the Salvation Army Hall. [5]

Flood water covering the Patterson River Golf Links 1934. The club house bottom right.

The community rallied to help those who were in distress. The police, fire brigade, life saving clubs, and boat owners were involved in rescue work while members of the Ladies Benevolent Society and church groups provided hot soup, scones, tea and dry clothing. One thousand five hundred homeless people in Chelsea were temporally housed in halls until the water receded and repairs to their damaged homes could be effected. [6]

State Relief Committee providing clothing to victims of flood in Chelsea.

Constable Gilding of Chelsea had a remarkable experience, for while effecting the rescue of a householder in Embankment Grove a snake which had taken refuge in the rafters of the house struck at his head, fortunately missing him. When he returned later the snake had disappeared.

With the passing of the rain and the receding of the water the various authorities had to consider repairing the devastation and undertaking measures to minimize damage should such an event occur again. It was estimated that £3000 was required to put the Mordialloc baths into ordinary repair and £1000 for Mentone baths. [7] A major problem faced by the Mordialloc Council was finding the money needed to carry out the repairs. Maintaining the foreshore had become an increasing burden with the program having a huge debit balance in 1934 of £2372/14/-. Providing dressing sheds, showers, and sewered convenieces required substantial sums of money. With storm damage additional money had to be found yet important sources of income had been lost. Revenue from baths rent and bathing box fees over the ten preceding years had averaged £221 and £360, but with the loss of a substantial number of bathing boxes and the inoperative situation of the baths the situation was gloomy. [8] Some years earlier the suggestion was put at Council that a parking fee be imposed on motorists using the foreshore but this was defeated. After the storm a report in the Moorabbin News again raised the possibly of a parking fee of six pence. [9]

Floods at Aspendale in 1934. Street disappears with water coverage.

After the floods of 1934, various public authorities continued to work to inaugurate schemes to protect the residents in the City of Chelsea from inundation from future floods and individual permit holders resolved whether to reconstruct their missing or damaged bathing boxes. Meanwhile the Mordialloc Council decided to repair the Mentone Baths and reopen them to the public but to close the Mordialloc Baths; decisions at the time that caused some anguish because of cost and loss of facilities.

Flash flooding at Centre Dandenong Road, Heatherton, 1998. Leader Collection.

Footnotes

- Argus, December 1, 1934.

- Moorabbin News, December 8, 1934.

- City of Chelsea News, December 8, 1934.

- The Sun, December 4, 1934.

- The Sun, Ibid.

- City of Chelsea News, December 8, 1934.

- Moorabbin News, January 12, 1935.

- Moorabbin News, March 30, 1935.

- Moorabbin News, January 12, 1935.