The Battle of Mordialloc

Major Robert Rigg.

Researching the establishment of the Methodist Church in the bayside suburbs of Mordialloc, Aspendale, Edithvale and Chelsea, I was interested in the contribution of R E Rigg. Referred to as Major Rigg in church publications of 1899 and shown in uniform led me to consider in what army he served.

Don Garden in his history of Victoria wrote:

“The increasing overlap between expanding colonial economies; the rising proportion of native born colonists and their nationalistic identity with the land of their birth; the broader consciousness which was reflected in the flourishing Australian literature; and the ‘invasion mentality’ of the colonists all helped to draw the colonists closer together. Victoria led the way in federation. The moves were a product of concern about external security. Since the 50s there was a degree of paranoia about the possibility of invasion; and the 80s with its unstable international situation & the widening interest of France & Germany in the Pacific caused alarm. This led to a rapid defence build-up in Victoria. Large fortified batteries were set up at swan Island, Queenscliff, Point Nepean, and on the shoals at the entrance to the Harbour. Security was there provided the troops didn’t land along the undefended coast. The Victorian Volunteer Artillery was disbanded & replace with the Victorian Artillery Corps & the Victorian Mounted Rifles. Cadet corps were established in state schools and rifle clubs encouraged. More Batteries at Portland Port Fairy & Warrnambool were set up. 1884 saw the Victorian Navy purchase 2 gunboats & 3 torpedo boats. 2 Barges on which gun platforms could be set up were established.

It was all right to be prepared but there was no one to fight. It was hoped that Victoria could help in February 1885 when news came from Sudan that General Gordon had been killed in the Sudan, but the offer was rejected by Britain. By March however, people were talking about, and even hoping for, a defence against a Russian invasion. Victorians believed that if Britain was involved in an European war, Melbourne would be a prime target. When Britain & Russia came close to war over Afghanistan in 1885, fortification works at the Heads were speeded up, the channel at the heads was mined, foreign ships were not allowed to enter at night & a number of old hulks were purchased to be sunk at the Heads if necessary. A new division of the Mounted Rifles was established in the country; people armed themselves, drilled in the city streets & attended patriotic meetings. Terms arranged with Russia in May brought a sense of disappointed anticlimax. This sense of vulnerability lasted for the rest of the 1880s and started a small flood of literature setting out what would be the likely outcome of invasions by the Japanese, Russians, Chinese & others (See Battle of Mordialloc).

This material ensured a build up of land forces. In 1890 2 new infantry battalions were added and the Mounted Rifles expanded; with colours changed from scarlet & blue two khaki A Battery was installed in Hastings to prevent access from Western Port.

Land Forces in 1891 totalled 7,180 military 2,045 rifle club members; 4,425 cadets and 10,000 school children who had been given rifle drill. The last Navy boat which arrived in 1891, was the torpedo boat “Countess of Hopetoun”.

The end of the Victorian Navy was in sight when in 1887 it was agreed that naval security for the colonies would be provided by the Royal Navy for which the colonies paid. [1]

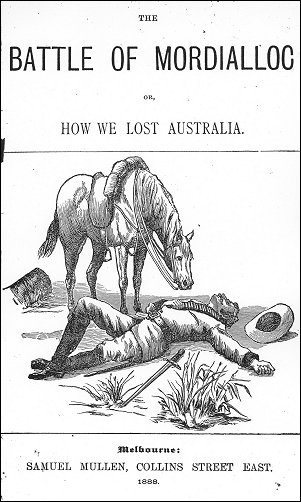

Garden’s reference to the Battle of Mordialloc in early colonial history intrigued me. I found it to be a 64 page book written in the 1880s. The writer in his introduction said he had written the book, a product of his imagination, to awake the readers to the possibility of invasion of Victoria by forces from Japan, China & Russia. This book costing one shilling was one of many books and pamphlets written at this time to stir people to action. [2]

Battle of Mordialloc. Courtesy La Trobe Library Rare Book Collection.

The book sets out how things are in the 1880s. The opening scene is set in the Victorian Parliament, and speaker after speaker stresses the development and the prosperity they enjoy. The theme of “we are big enough to stand on our own two feet” and that “we have to separate from Britain: come to the fore, and any speaker who opposes this view is immediately howled down. Eventually, the States do separate from Britain, and each colony goes on their own way.

The writer is unhappy about this course of action, and he points out the hidden threats within the colony. The Gold Rush allowed a large number of Chinese into the colony, and these were gathered into rather large groups where they worked their market gardens. As well, nearly ¼ of the population, because of their religious affiliation, gave their allegiance to a foreign pontiff in Rome. The loyalty of these people in any future conflict would be under question.

The threat of foreign invasion was intensified when Great Britain declared War on Russia and China joined with Russia in this battle. The Defence Force was very small but they started to prepare themselves for any invasion that took place.

Melbourne Cup Day was always a great celebration with the majority of Melburnians going out to Flemington for the day. Cup Day 1897 was not different – a lovely warm day and everyone enjoying themselves, but no one noticed the sudden departure of the Premier and senior Government Ministers. A great hush came over the crowd, followed by a mild hysteria when a special edition of ‘The Argus’ arrived at the Racecourse with the news that a large Russian Invasion fleet was on its way to Melbourne.

The writer rushes home where Father is preparing next Sunday’s sermon, and daughter is putting finishing touches on things she was needing for her wedding on the following Saturday. Her fiancé comes in to tell her that his company of which he was a captain had been called up and he was off to war. Out of earshot from the family the captain, the brother-in-law-to-be, told him that the situation was extremely bad. The next day, the writer joined the great rush of volunteers prepared to defend their city. Most of them had only the experience of school cadets behind them.

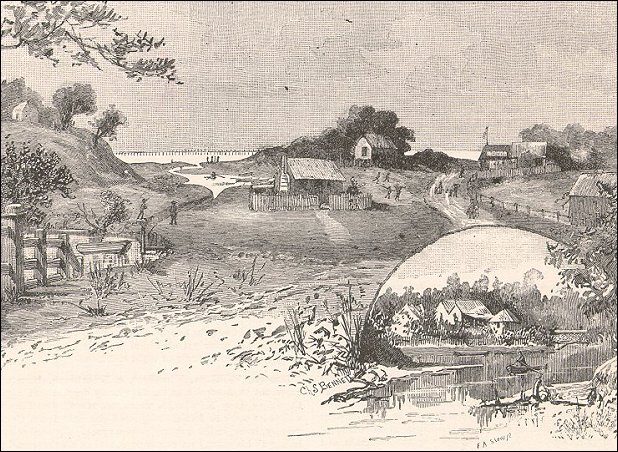

It was Saturday, after a very inadequate period of training, that they were called into action, as the invasion forces were coming. At first they though they were being sent to Frankston, but they were taken off the train at Mordialloc. The men moved off in the rapidly growing dusk to take up positions under the guidance of a staff officer. As they did so the wild fowl were scared from their haunts by the Mordialloc Creek. The tall gum trees loomed large above the surrounding bush and tangled undergrowth.

Mordialloc Creek, 1888.

Patrols were sent out and sentries posted as a precaution against a surprise attack, the remainder of the men were ordered to fall out and pile arms. The writer said the troops were thoroughly fagged out due to the haste and excitement of the last few days. They had eaten nothing since morning and were famished.

The enemy had staged a diversionary attempt at going through the Heads but the main group had landed at Hastings and were heading towards Melbourne. Orderly sergeants warned them to expect an attack from the enemy the next morning. Before lying down each soldier was given a ration of rum was distributed along with a hundred rounds of ammunition and two day’s rations.

The writer described the country to the front of the troop’s position as a flat plain clear of bush and offering no natural barriers to an advancing enemy. Away to the left stretched a long range of the blue Dandenongs. On the right was the magnificent sweep of the Bay with its shingly beach, bordered with forest and dense scrub. Two companies of soldiers lined the mouth of the creek under the cover of ti-trees and other bushes which lined its banks. On a slight rise at the rear of the township was a battery of field guns completely screened from view by a thick hedge of prickly cactus commanding the approach from Frankston

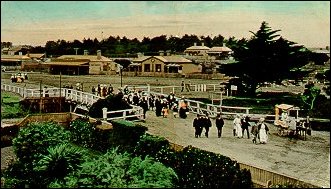

Mordialloc Township and Bridge, c1910.

It was one sided 6000 fighting against 50000 but they inflicted many casualties. After a two hour artillery duel the enemy, “composed in the main of merciless Asiatic,” advanced. The whole plain was strewn with bodies, “friends and foe alike, rigid and silent in death or writhing in agony in the fierce moonday sun gasping out a piteous appeal for water which never came.” The small group of defenders distinguished themselves so much that later the Russian General commended them for their bravery. The wounded were taken back to the City to find that it had been taken over by larrikins who were looting many homes, including the writer’s.

Most of the wounded and others had barricaded themselves in St Patrick’s Cathedral. It was here that the writer found his father and his sister, who were holding her injured dying fiancé in her arms. He died on the day that was to be his wedding day.

All over the city the Chinese soldiers committed many atrocities and order was only restored with the arrival of the Russian General.

The occupation continued for quite some time, but the writer, and his sister managed to escape and the final pages see them on a ship heading to England, where things were much better for all.

Footnotes

- Garden, D., History of Victoria, 1988 page 256.

- Herbert Ainslie, The Battle of Mordialloc or How We Lost Australia, 1888, Samuel Mullen, Collins Street East.