Mornington Versus Mordialloc: The Fateful Football Match of 1892

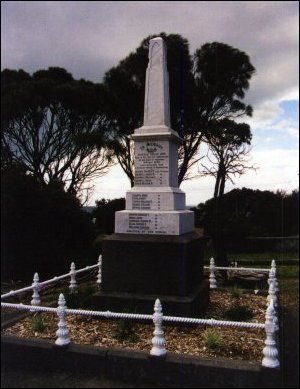

Memorial on the Mornington foreshore to the footballers who lost their lives in a drowning tragedy.

Mordialloc Football Club was formed in 1891 but its second season produced the event which was the club’s most memorable in over a century. In the 1890’s football at the outer suburban level was still largely a social game where teams arranged matches on a casual basis against neighbouring clubs. There was no official competition with a ladder and finals as we have now. So after a successful 1891 inaugural season Mordialloc club members, looking forward to the 1892 season, organised fixtures against Cheltenham and Mornington to begin the year’s football. The Cheltenham game was cancelled because the ground was under water after torrential rain. Mordialloc club selected a team to play Mornington on Saturday 21st May and included some well-known locals including Rennison and Rigg. No one could have known what a fatal fixture this match was to be.

The Mornington team agreed to play an away game and made arrangements to travel up to Mordialloc. The railways had just completed an extension of the line from Frankston to Mornington and this would have been the normal way of travelling to Mordialloc. However, Charles Hooper, a 35 year-old member of the team who was an experienced sailor and fisherman, offered an interesting alternative. He invited the team members to use his boat Process for a sea trip to the Mordialloc game. Hooper skippered the craft, known as a yawl, which was over nine metres long with a main mast of similar length. Hooper told the young men that he would use his racing sails for the trip, the ones which had won him regatta honours off Frankston and Mornington in the recent past. At a meeting prior to the match 12 out of the twenty players voted for the novelty of a boat trip, and so all but one of the team set out after lunch on that May Saturday which was to mark the greatest tragedy in the Peninsula’s sporting history, if not that of Victoria as a whole. Two of the original twenty dropped out so the 17 from the boat were joined at Mordialloc by Charles Allchin who came by train from his work in a city architect’s office. The fifteen mile trip across the bay had been uneventful, though one man who made the return journey by train said that William Coles had played a song "The Ship That Never Returned" among his medley of cornet tunes. His teammates, singing as they sailed, were not to know of the terrible irony that song promised.

The match at Mordialloc began about three in the afternoon and ended in near darkness at 5-30 p.m. The result was a draw, each team having scored two goals. In those days behinds did not count. The game was played on the original Mordialloc ground in the beach park, not far from the pier.

The Mornington team boarded their craft at Mordialloc pier around six o’clock with only a few locals to say farewell. Charles Hooper let it be known that he expected to reach Mornington between 8 and 9 p.m. Later, those who said goodbye at the pier gave evidence that the travellers were sober and in good spirits. Allchin joined the boat travellers but three men who had come by sea returned in the train. They were Coxhell, the baker, a lad called Shultz and Mr Short, the bank manager, who said he boarded the train because he knew his wife would be worried about the sea trip.

Off Frankston Process passed some fishermen who later said the men were singing and appeared to be travelling without any trouble. That was the last time any of them were seen or heard alive. No one knows exactly what happened next but a reconstruction of the tragedy gives this likely sequence of events. There was a stiff NW breeze that night and the boat in full sail had to be ‘ballasted’ by the whole team sitting on the windward side to stop the craft toppling. As the yawl reached Pelican Point, near Mt. Eliza, a sudden squall placed great strain on the wire halyard holding the sail. This snapped and the sail ran down causing the boat to lurch quickly with the weight of the men on one side. It capsized, throwing the occupants into the sea. In the darkness and with waves beating around them the men struggled to right the craft or climb on board. No one succeeded and one man got tangled in the rigging. One can only imagine the sheer terror in the minds of those unlucky footballers as they clawed and fought for a grip on the smooth underside of the vessel only to be washed off by the waves. Exhaustion soon ended their struggle. Any that tried to swim for the shore did not make it. All were drowned.

Back at Mornington, that Saturday night was to become the blackest ever in the town’s history. There was a gradual build-up of concern and then deep worry about the young men from the town. The first to be concerned was Mr Short, the manager of the Commercial Bank, whose train had reached Mornington at about 8 p.m. By about 9-30 p.m. he became worried that his young accountant and team mate, William Grover, had not called in to collect his duplicate set of bank keys as he had promised to do. Short went to Grover’s home where he informed Mr J Grover, the young accountant’s father. Grover senior became so worried that he set out by horse and buggy to reach Mordialloc and find out about the football team’s departure. Mr Short then went with a friend down to the Mornington pier to see if there was any sign of Process returning. The wait was fruitless. When midnight passed with no boat in sight it was clear that something was seriously wrong so Short went to Rev. Caldwell’s home to inform the minister of the concerns he had for the team which included Caldwell’s three sons.

The worry now became panic as Caldwell rushed to awaken Sergeant Murphy of Mornington police. He in turn roused the postmistress so that a telegraph message could be sent to Mordialloc. She could get no reply. Twenty-four-hour electronic communication was in the future. Telephones were not connected to Mornington at that time either. So Mornington people who had relatives and friends in the football team were visited and informed of the non-appearance of the boat. Doubtless, some had already begun to fear the worst. Many made dashes to the pier or the surrounding beaches to no avail. Mr Short and a friend, Mr McLellan, travelled by buggy towards Mordialloc only to meet Mr Grover coming back with the news that the team had left as planned the previous evening. It was now around four in the morning and the town could do little else but wait for the dawn.

Several boats searching the coast early that Sunday found the upturned Process lying in the sea on Pelican reef. There were bags and belongings strewn about the area as well. The upturned boat was towed back to Mornington and, when righted, the naked body of Alfred Lawrence was discovered tangled in the rigging. He had discarded his clothes, probably to make swimming easier. During that Sunday and for days after there were many vessels out searching for the rest of the team but no other bodies were discovered. This was despite the efforts of many sailors and the officers on the Customs launch. The Ports and Harbours Department vessel, Lady Loch, which had dragging equipment aboard was also sent to the area but none of the other men were found.

There was an inquest into the death of Albert Lawrence whose body was taken to his father’s main street shop. The verdict of accidental death shed little further light on what people knew to have happened. The town grieved openly at the funeral of young Lawrence when he was buried at the Mornington cemetery. The wider community was shocked as well, none so much as the people of Mordialloc who were the last to see the men on dry land. Telegrams and messages of condolence came from everywhere, one from the Governor of Victoria, Lord Hopetoun. A public meeting at Mornington established a committee for relief of the victims’ dependants. It included many politicians and professional men. Eventually, over sixteen hundred pounds was raised. Seventy-five pounds was used to erect a memorial at Mornington and the rest went to the families of those who died.

In retrospect it is hard to grasp the enormity of the sadness and hardship this event brought to the little town. The Rev. Caldwell of the Presbyterian Church lost three sons aged from seventeen to twenty one. Charles Hooper’s fourteen-year-old son died with him but he left a wife and three other children. Two other players had wives and children, while Grover lost his brother and son. And then there was the tragedy of Charles Allchin who came from work in the city by train, only to join the fated yawl at Mordialloc for the rest of the trip. Short and the two others who came home by train after spending the outward journey on the boat must have spent the rest of their lives wondering over that twist of fate. Mornington lost a large portion of its young men that night and was a grieving town for years after.

On the foreshore at Mornington a monument stands as a memorial to the fifteen men who died over a century ago. They were:

Charles Ernest Allchin, 19.

James Reid Caldwell, 21.

William Lindsay Caldwell, 19.

Hugh Caldwell,17.

William Coles, 23.

John Comber, 31.

James Firth, 17.

William Grover, 25.

William Grover, 17 (nephew of above).

Charles Hooper, 35.

Charles Hooper, 14 (son of above).

John Kenna, 18.

Albert Lawrence, 19.

George Milne, 38.

Charles Williams, 23.

Carved wreath on the back of the memorial on the foreshore at Mornington.