My VP Day In Mentone

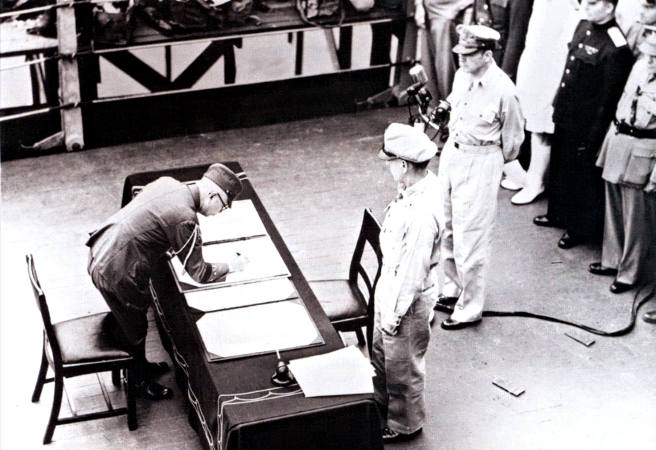

General Yoshijuro Umezu signs the Japanese document of surrender on September 2, 1945.

When the Pacific War ended on August 15, 1945 I was only ten years old but the day stands out in my memory. On that day I had risen early in order to fulfil my duties as an altar boy at St Patrick’s Church, Mentone, where the priest, Father Daly, offered prayers of thanksgiving in anticipation that the end of the war was about to be announced. Prime Minister Chifley’s gravel voice was soon to be heard on the wireless making peace official. Some of the churchgoers that morning stayed behind in excited conversation as the news of the peace sank in. For me, though, as I walked home the realisation of peace provoked a strange element of uncertainty. At that point in my life most of the experiences I could remember were those in a world dominated by war. And most of my experiences had been pleasant.

Growing up in Mentone during the war had been largely an enjoyable, safe and positive experience. As kids at school we knew all about the war; after the Darwin bombings there were trenches in the school playground and much discussion of warplanes and other weapons. The kids who could draw Spitfires, Lancaster bombers or warships in their exercise books were high in the pecking order. The movies that we were allowed to see made the war seem exciting. We saw the Allies winning in many parts of the globe and witnessed the roles played by all of the services. Submarines, tanks, anti-aircraft guns, jeeps, battleships and the full range of combat aircraft became the normal subjects of interest for schoolboys at the time. Models and picture cards of these war weapons were prized and coveted by most boys. So were our sets of toy soldiers. What the girls held dear did not interest us at the time. Weekly comics from England such as Champion gave us stories from the European front where it appeared that Rockfist Rogan, RAF, and his cheery comrades were beating the Germans on their own.

In Mentone there was occasional excitement when troop trains went through the town on their way to Mornington Peninsula camps which housed American soldiers from 1942 on. We were amazed to see the Yanks, as everybody called them, sitting and dangling their legs from the open doors of carriages, seemingly unworried by the station platforms that were encountered at each suburb. My father said that there were no platforms at the American railway stations shown in the movies, implying that in USA legs could be dangled from trains with impunity. The Yanks sometimes threw packets of chewing gum to the kids near the railway, often whistling and yelling in strange accents as they passed the excited railside spectators. Australian men in uniform often appeared in Mentone or nearby suburbs. Many spent their leave visiting home and there were often uniformed visitors to the local beaches or the Mordialloc carnival. To the kids who were growing up during the war none of this was unusual and the servicemen and a few servicewomen always seemed happy and healthy when we saw them. We were protected from the worst of war’s horrors. Adults tended to keep gruesome images away from children’s minds and the media was heavily censored. There was talk about what prisoners of war were suffering and other terrible happenings ‘up north’ but we had little realisation of their shocking nature. One day in 1944 I saw a woman in St Patrick’s Church crying uncontrollably as she knelt to pray. My mother later told me quietly at home that the distraught woman’s son had been killed overseas. I received a faint inkling of what war did to people in the observation of sadness on that woman’s face.

Children’s lives were not harshly affected despite rationing and the withdrawal of some confectionery and toys from sale. At the shops near the State School and St Patrick’s (Blake’s and Roach’s) there were still lollies to be bought and the shopkeepers produced home-made ice blocks of many flavours which helped us through summer days.

At school the rubber shortage meant that sporting goods such as footballs and basketballs were very scarce but kids made up other energetic games like British Bulldog, played marbles, or used the cherry pips in season to run betting activities where ‘cherry bobs’ could be won by accurately tossing one into a small hole. At St Patrick’s a less reputable game called ‘concentration camps’ involved the imprisonment of junior boys during recess times in a compound surrounded by boxthorn bushes at the bottom end of the school property. The grade eight boys, some of whom amused themselves by mimicking Nazi sadism, would forcibly capture little kids and hold them in the makeshift enclosure while they subjected them to ‘torture’ by sticking prickles into them or tying their hands behind their backs with the tough ‘wire grass’ that grew prolifically in the area. When the bell rang for return to class the prisoners would be tied down and made late for lessons, ensuring the further indignity of unfair punishment from the nuns who ran the school. Despite episodes of bullying like this most school children in Mentone were not affected badly by the war which was having its terrible impact in other parts of the globe.

VP Day arrived with a promise that things were about to change. How those changes would unfold certainly remained a distant mystery to me as I walked home from the church that August morning in 1945. However, I soon became aware of excitement in the air and a mood of happiness mixed with relief. My parents were talking about the coming of peace and the return home of relatives who were in the army, while neighbours called over the fence to chat about the good news. But later that day I had a VP Day experience that remains indelibly marked on my memory.

A schoolboy friend, Neil Pickles, lived near us and he called around to say he was about to sell Heralds at his usual spot in Mentone Parade not far from the railway station. I decided to go with him, having time on my hands on this welcome holiday. The Herald came out early and had several editions on that day with people coming from everywhere to buy it and read about the coming of peace. The front page had a photograph of the American warship, Missouri, where the Japanese leaders were shown signing the surrender documents. That Herald was so popular that Neil could hardly keep up with the demand so he gave me some papers to sell down near the Florence Street corner about fifty metres away. I was nervous about my new role but pleasant surprises began to happen in rapid succession. Buyers appeared frequently and most gave me silver threepences or sixpences, with many refusing to take any change (Heralds cost twopence at the time). Soon I had sold out and Neil gave me more papers which also sold rapidly. He renewed his supply from Bancroft’s newsagency several times as the roaring trade continued. A few men gave one shilling or two-shilling coins for their papers and gave us the change as tips, so the pockets of my khaki shorts began to bulge and jingle. Most of the buyers were men but a few women also bought Heralds and they were equally as generous. The most amazing thing for my young mind to absorb was the change in mood of the people in the main street. Previous to this day adults that I had observed in the town were fairly serious when they went shopping; strangers were not in the habit of greeting you except where necessary and then in a formal way. VP Day was different. Blokes spoke to me with friendly words, some calling me ‘pal’ or ‘mate’ as they parted with their money. As a kid it felt good to be accepted as a member of the celebrating community. People chatted to one another in friendly exchanges and some ran for the train in an excited rush to get into the city.

Around 4 p.m. I witnessed an amazing episode in Mentone’s main street. From the direction of the beach (and the hotel) there appeared a group of people walking about eight or ten abreast in the middle of Mentone Parade. Not only were they walking but they were singing and doing an occasional kick of the legs as they sang ‘Knees Up Mother Brown’ and other ditties. Some appeared a little unsteady but as the group’s members all had arms around one another they made good progress towards the station which seemed to be their objective. To me this interlude was astonishing. Before this I had never seen an informal exhibition of dancing or singing in any public street, let alone a large group like this happily marching in the shopping centre without a care for who might see them. There were a couple of women in the group and one was a lady who never missed Sunday Mass at St Patrick’s and had always seemed most serious and demure in the past. I later realised that she was in that main street celebration because her son would now be coming home from air force duties to the north of Australia.

As the afternoon wore on the sales of newspapers began to slacken off and Neil Pickles eventually returned to the newsagency with the leftovers as I went home. That afternoon had been a happy one for everyone in Mentone and for me it had been of special significance. I had learned that the end of the war had a depth of meaning for some people that I had not appreciated. The public displays of joy and relief were related to the fact that no more lives of loved ones would be lost in combat and the prisoners of war would be returning. I realised that some families were more directly involved in these matters than my own.

VP Day brought great happiness to many people. For me it was a step along the way to self esteem and independence. When I had paid for the papers and counted the money left over I had more than seven shillings in tips, an amount that I had never received in one day to that time. What made it so enjoyable was the fact that I had met adults on an equal footing and had been given an independent recognition backed up with friendly greetings and many tips. For a shy ten-year-old the day had been a marvellous confidence builder. Never mind that my mother made me put most of the money in my money box; I was proud of having earned something from my first venture into the commercial world. Or so I thought at the time.

Of course VP Day in Mentone brought a multitude of other joyous experiences and the celebrations later developed into a free City Hall dance as well as many private parties. Later on all of us at school received silver victory medals with red, white and blue ribbons attached, and life began to change as restrictions were lifted. For one thing you could buy real chewing gum again. A new mood developed as peace-time activities resumed. I have forgotten how most of these affected me but, after nearly sixty years, I have special memories of being in Mentone’s main street on VP Day.