Poliomyelitis: Infantile Paralysis

In Victoria in the late 30s and early 40s and 50s a highly infectious disease known as poliomyelitis, polio or infantile paralysis struck down many individuals. These epidemics had an enormous impact on the psyche of society and in particular on our local communities.

The disease is caused by a virus which invades the central nervous system of an individual and multiplies in the intestines resulting in various degrees of paralysis. Nerve cells that control muscular movement are destroyed. In some cases total paralysis can occur within hours. The virus enters the body through the mouth being spread from person to person through infected faeces or by airborne particles. [1]

Poliomyelitis was known as infantile paralysis due to the number of children who were stricken with the illness in the early twentieth century as it mostly occurred in children between the ages of five and ten years. It is not, however, exclusively a children’s disease.

The infection spread rapidly in Australia in the 1900s and was not controlled until the discovery of a vaccine that almost eradicated the disease towards the latter part of the century. However, immunization against the infection is not compulsory and therefore the incidence of the disease remains a threat today. The World Health Organisation reports that while the number of polio cases globally has dramatically reduced through the institution of an immunization program there has been an increase of cases in India and Nigeria. There is no cure for the disease it can only be prevented. [2]

Early symptoms included fatigue, headaches, vomiting, constipation, stiffness of the neck and sometimes diarrhoea and pain in the extremities. The incubation period varies ranging from four to thirty five days.

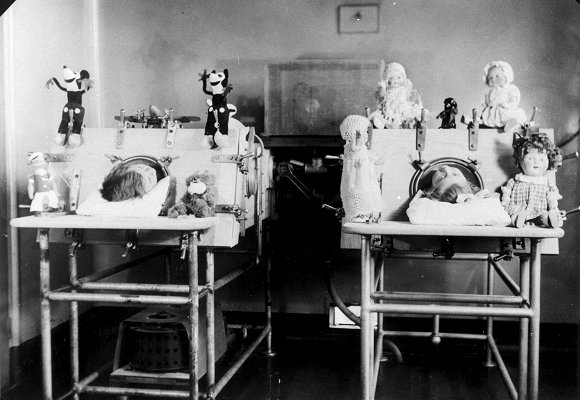

In cases where the nerve cells in the respiratory centres were destroyed leaving the patients incapable of breathing on their own they were placed in iron lungs or artificial respirators. The respirator forced air into and out of the lungs keeping the patient alive. The patient was placed in the iron lung with only their head exposed, an alarming situation for young patients. Former sufferers tell of their fear of the large frightening contraption that occupied space in polio wards of hospitals. Nevertheless it was this mechanical device that was the life support that facilitated the recovery of many polio victims.

Polio patients in iron lungs. Courtesy Royal Children’s Hospital Archives.

To enable patients to leave hospital and move between home and aftercare treatment a large pram bed was constructed to help parents deal with the difficulties of home care.

In became a familiar sight throughout Melbourne suburbs to see patients wheeled around in these large prams, and it was not an easy task for the many mothers who travelled on the train system, which was the only public transport able to accommodate the large pram/beds. Patients returning to the Children’s Hospital would be walked the last mile from the central railway station to the hospital. Patients who were confined to the use of wheelchairs still experienced the exhausting travel and required the constant supervision and help from full time carers.

Over time several theories developed regarding the treatment of the infection. Australian nurse Elizabeth Kenny in Queensland first introduced stimulation of the muscles in 1910 when she treated her first polio patient. It became a notifiable disease in Queensland in 1911. Poliomyelitis was declared a notifiable disease throughout Australia by the 1920s. In the initial stages Sister Kenny’s form of treatment was controversial.

There had been several outbreaks of the disease throughout Australia from the early years of the century but the 1937-1938 epidemic was the most serious in Victoria and caused fear throughout the State. Very little was known on how to combat this disease and as it spread quickly effecting children, panic was inevitable.

Two thousand cases were reported. This placed enormous strain on the Royal Children’s Hospital with the great number of children affected. A government grant was awarded to the hospital for a new building at Hampton where 112 polio patients accommodated there as well as a new ward set up at Frankston Hospital for children in rehabilitation.[3]

The prevalence of the disease in Victoria caused concern in other States, particularly New South Wales. Up to twenty crossings into NSW were patrolled by police. Special police were stationed at railway stations, aerodromes, bridges over the Murray River and at the wharves in Sydney to control the possibility of the infection being spread from Victoria to New South Wales. Vehicles were stopped and checked. Unless those in charge of the vehicle had proof that any child under the age of sixteen years travelling in the vehicle, had not had contact for 21 days previously with known sources of the virus or had been exposed to the virus or had attended a school closed due to the illness then the vehicle was refused permission to cross the boarder into New South Wales. [4]

In the municipality of Moorabbin, the council took measures to control the spread of the disease, by placing children who were believed to be at risk of spreading the infection or who had come into contact with an infected person, into quarantine. Estate agents were requested not to let houses to people from areas that were known to be affected by the virus ‘unless they produce a certificate from the Metropolitan Health Officer Dr. Merriless’. For local medical practitioners, who were in doubt regarding any suspected case of paralysis, the Health Department arranged for a consultation with specialists. The Town Clerk would supply to any medical practitioner the names of the consulting specialists. There appeared to be willingness throughout the municipality of co-operation from parents because of the seriousness of this disease. [5]

A report in the Moorabbin News in August 1937 the Health Officer for the City of Moorabbin, Dr A Fleming Joyce, went to great lengths to assure the residents that the “measures taken to combat the infantile paralysis epidemic in Ormond, McKinnon and Bentleigh have apparently been successful". Dr Joyce urged residents to take care to guard against the disease. He congratulated the residents for the way in which they had carried out instructions to isolate the epidemic. The instructions were strict; keep away from crowded places, especially protect the children from these areas, make sure that they did not come in to contact with children from infected areas. Visitors from infected areas were not permitted to stay or visit hotels in the area or rent houses in the City of Moorabbin.

Within the Municipality of Mordialloc restrictions were also in place and great care was taken to make the residents aware of the dangers of the spread of the viral infection among the children. The Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Grinrod, advised the council that there were no cases reported in the City of Mordialloc. However, there were still reports from Chelsea, and a number of people coming from infected areas such as Bentleigh and Ormond had to report daily to the Medical Officer of Health. A warning was issued to parents to take care and watch for cases of infection where school children were helping tradesmen on their rounds; for example, the milkman or the baker delivering bread to the residents’ homes. ‘Immediate steps [must] be taken to stop the practice during the epidemic’. [6]

In some instances schools were closed in the winter of 1937. Mentone Grammar School reopened after a three months closure due to the infantile paralysis epidemic. During that period the school experienced considerable financial hardship. [7]

Mentone resident, Leo Gamble, recalls the trauma of being sent to Fairfield Hospital because he suffered from similar symptoms to infantile paralysis. His vivid memory of being placed in an ambulance outside his home in Charman Road when he was just three years old has stayed with him from that time. He was placed in an isolation ward with many other children, away from his family and doubtless was frightened by the experience. He was later returned to his home when it was diagnosed that he was not another victim. Nevertheless, this incident left him with the very vivid memory of frightening times. [8] The medical professionals dealing with this serious outbreak of the infection treated patients very cautiously to avoid neglecting any genuine cases of poliomyelitis. There are many similar stories to be told.

Paralysis after-care was available at many centres throughout the state. A clinic was set up at Mentone in June 1938 at the City Hall, Mentone. The clinic was under the personal supervision of a qualified masseuse, Miss Hopkins. Patients were brought to the centre daily from other districts in the municipality from Cheltenham to Chelsea. One important aspect of the daily routine was that the children’s mothers would assist Miss Hopkins by preparing them for the treatment, removing the splints on their legs and any other necessary assistance they were capable of dealing with at the clinic. When a patient was discharged from hospital they were in need of daily treatment in an after-care facility and this became the responsibility of mothers who had the task of getting the patient to the clinic at Mentone. Initially this treatment was only available in Melbourne and the opening of the clinic at Mentone was a significant help to the local residents. It was expected that there would be an increase in the number of patients that would need after-care treatment.

It was reported in The News, that the clinic was financed by a fund established by the Mayoress of Mordialloc, Mrs F Herbert, and the clinic would be operating as long as was necessary, depending on the circumstances. The use of the meeting room at the City Hall was by permission of the council who also supplied necessary carpets and screens. A plentiful supply of blankets came from the Mayoress’ fund and donations were received from various organizations willing to offer their support. It was stated in the article that none of the cases under treatment at Mentone were of a serious nature and all patients were expected to make a full recovery. The children who attended the clinic were from Aspendale, Chelsea, Mordialloc, Mentone, Cheltenham and one child from Black Rock. [9]

Poliomyelitis control was made possible when in 1949 an American bacteriologist John Franklin Enders and his assistant discovered a method of growing the virus in the laboratory. Following this success the American physician and epidemiologist Jonas Salk developed a vaccine. Since that time some victims of poliomyelitis who originally made good recoveries from the illness have had a recurrence of symptoms of the poliovirus so research into the disease continues.

Footnotes

- World Health Organization, Poliomyelitis, Fact Sheet No 114, 2003.

- World Health Organization, op. cit.

- Yule, P., Royal Children’s Hospital: A History of Faith, Science and Love, 2001, pages 202-3.

- Moorabbin News, September 4, 1937.

- The News, July 30, 1937, page 1.

- The News, August 13, 1937, page 1.

- Rundel, James, Against All Odds: History of Mentone Grammar School, 1920-1988, 1991.

- Hahn, R., Interview with Leo Gamble, 2003.

- The News, June 17, 1938, page 4.