Henry Dendy: The Squire Who Had No Head For Business

Henry Dendy, Pioneer. Courtesy Bayside Historical Society.

The failure of Henry Dendy, founder of Brighton and first pioneer of Moorabbin, was one of the most spectacular and somehow poignant reversals of fortune in the early history of Port Phillip. He should have become one of the colony’s wealthiest men, but in four short years he was reduced almost to ruin because, as it was said, ‘he had no head for business’.

Dendy was aged 40 when he arrived in Melbourne in 1841. Probably through impulse rather than good judgement, he had acquired in England a ‘Special Survey’ from the Commissioners for Land and Emigration – the right to select 5120 acres (or eight square miles) or land, virtually of his choosing in the Colony, about which he appears to have known very little. For this right, he paid £5120 – or an astonishing £1 an acre.

The regulations regarding land settlements of this type had been formulated only in 1840 to attract settlers of financial substance to Port Phillip to develop lands considered to be raw and of marginal value. But the explosive growth of the settlement during the first half dozen years had made the provision wildly anachronistic, even from the moment it was promulgated.

In 1841, land in Melbourne was selling at as much as £15 a foot, and even open spaces around the town were being snapped up at a price per acre ten times or more what Dendy had paid.

Dendy had come from farming stock in England, but seems to have had no great experience in agriculture. He had been a brewer for a time, and then inherited family farms after the death of his father. Dendy had used much of the proceeds to purchase his Special Survey and by doing so had achieved something of a financial coup. He had no real agricultural ambitions, no pronounced speculative impulse, and there was certainly nothing of the hard-headed businessman about him. Weston Bate in his A History of Brighton writes best about Dendy and his motives;

He always bore himself with quiet dignity (and) impressed his contemporaries in Australia as being strangely a dreamer, the kind of idealist who may nourish, quite unsuspected for years, ambitions of the strongest nature. By all accounts, he was consumed by the desire to live the gracious life of the country gentleman. And that may be the vital clue to the understanding of his whole life.

Dendy’s arrival in Melbourne was greeted with something approaching a flourish of trumpets, and much consternation in both official and unofficial circles. The burning question was about how and where he would exercise his right of acquisition, for there was no relationship between the price Dendy had paid per acre and the prevailing value of property in and around Melbourne. Governor Gipps of New South Wales had speculated that Dendy’s survey could have been worth £100,000. Dendy himself, shortly after his arrival, had refused an offer of £15,000, declaring it was worth £50,000, even before his selection had been made.

During his search for a suitable, and officially acceptable acreage, Dendy enlisted the aid of the flourishing businessman Jonathan Binns Were as manager, and later, partner. Were, had arrived in Melbourne in 1839 with a shipload of merchandise for which he had paid £9000 and is reputed to have sold it for £70,000 and had the reputation of an astute businessman, well-versed in the doings of the colony. With his brother George, he had also established the well-regarded business of Were brothers, a firm highly successful in merchandising, and as agents for shipping and land.

Were vigorously advocated for Dendy’s acquisition of a valuable acreage around Williamstown, but Governor Gipps and Superintendent thwarted this. They held that Dendy could only acquire land beyond the five-mile limit of Melbourne, a requirement that forced Dendy to choose an acreage that was to become Brighton in the Parish of Moorabbin.

Dendy’s ambitions to become the squire were implemented almost immediately after taking possession of his Survey in 1842. H. B. Foot, the surveyor, was commissioned to draw up plans for ‘The Brighton Estate’ which, with its elaborate crescent design, great size and lack of water were a grandiose oddity within the Port Phillip Wastelands. Dendy and Were also began selling off allotments on the desirable seafront for the construction of marine villas, one of which was to be occupied by Jonathan Were, and another, the grandest of all, by Dendy. It was a splendid, two storey mansion called ‘Brighton Park’ which significantly became better known to local residents as ‘the manor house’.

Late in 1842, Dendy received the second of his fine entitlements – the shipment of ‘Dendy’s immigrants’, workers for his estate whose passage from England had been paid by the Crown, one approved emigrant for every £20 spent on land, all part of the splendid package Dendy had obtained with his purchase in England. There were 139 in the contingent, including many children, but also a large number of workers with agricultural skills. But Dendy had virtually no agricultural duties to employ them. The inundation embarrassed him and he was unable to provide work or lodgings for most of them. The calamity faced by the workers, who themselves had gambled their futures on Dendy’s Brighton, represented the first of Dendy’s many failures.

About this time, the soaring fortunes of the colony underwent a catastrophic reversal. The boom became bust when the speculative excesses of the first years rebounded, money dried up, trade withered. The established wealthy and the newly rich were hit, as were the poor, as always. Bills to Dendy were dishonoured and land purchasers were unable to pay what they owed to both Dendy and Were.

In 1844, three years after the great experiment of Dendy’s Brighton, Dendy transferred a half share of his estate to Were for £3000, but this sum, even then, had to be met from the sale of lands which were hardly selling at all. About this time, H. B. Foot went bankrupt. Jonathan Were, the shining star of Melbourne business who had achieved such brilliant successes earlier, was also in trouble. Dendy, who had seemingly retreated from the running of the estate, leaving this to Were, then made his fatal business decision; he lent Were £1500 to secure his colleague’s debts, resulting in his own acute financial embarrassment.

By December 1844 the whirlwind had begun to engulf the dreamer Henry Dendy. His estate was seized under an order of sequestration by the Union Bank. He managed to save ‘Brighton Park’, having previously settled this property on his wife on the basis of her investment of a £400 dowry in the Special Survey order. Everything in Dendy’s name was stripped from him. In 1845, his household and farm furniture, stock and other goods were disposed of at a Sheriff’s sale for £70.

Dendy left Brighton and resumed his life as a brewer in Geelong, then farming properties outside Melbourne and in Gippsland. He died in Walhalla, after a characteristically unsuccessful engagement in a mining venture, in 1881. Dendy never achieved the assured life of the country gentleman which he had aspired to with such longing, and which had so consistently eluded him. His faithful friend and worker, John Booker, one of ‘Dendy’s Immigrants’ who had stayed with Dendy for many years, recorded the most apt epitaph:

‘He was a good , honourable kind master,’ Booker said. ‘But no businessman’.

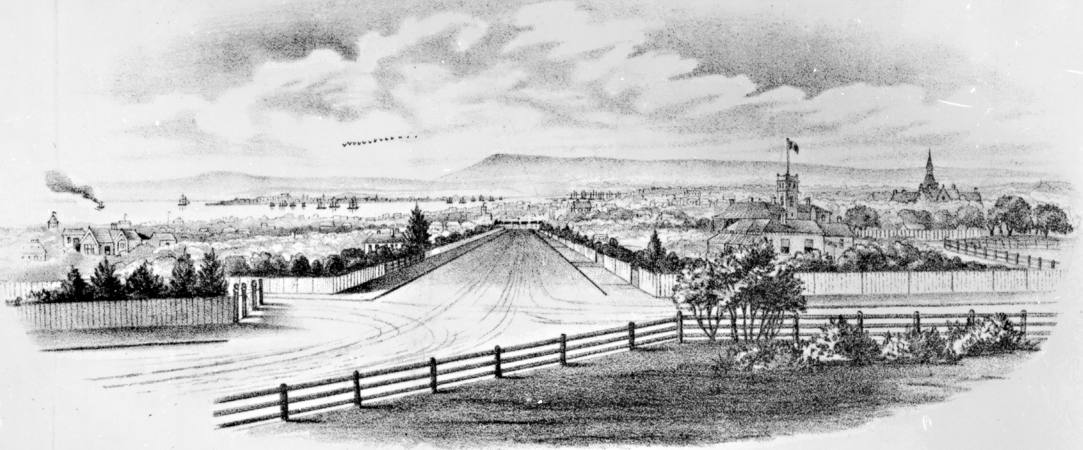

Brighton Landscape. Intersection of New and Were streets, C1860. Courtesy La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.