With the Sisters and the Brothers in the 40's

St. Patrick's School and Church, Mentone.

In the 1940’s most Catholic children in Mentone and its closest suburbs went to St. Patrick’s (St. Pat’s) primary school. At that time the school building had a dual purpose. The hall section at the bottom was used as the church and four upstairs classrooms catered for the whole school enrolment consisting of over two hundred. There were four nuns who ran the school with double and multiple grades in each room.

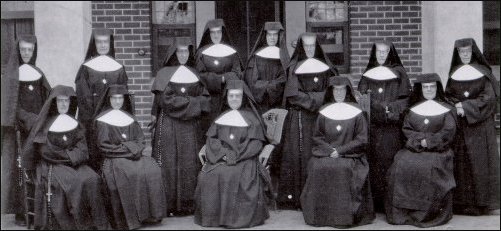

Members of the Brigidine Order photographed at their convent at Horsham in 1930’s.

At that time Catholic primary schools were almost entirely nuns’ schools. The young pupil would become familiar with the black-habited woman whose only visible flesh was on her face and hands. Even her forehead was covered by a stiff white piece attached to her black veil. At St. Pat’s Sister Agatha was the redoubtable doyen of teachers who took preps and the first two grades and had done so for as long as anyone could remember. She typified the stern Irish approach to Catholic education practised then. Religion permeated every part of the school day. She ensured that prayers were recited before class and at the end of the day as well as at times in between, including the Angelus as the school bell rang at noon. Her unmistakable emphasis on religious ritual and beliefs left no doubt in children’s minds that secular subjects were not the main reason for coming to school. She and the other nuns commanded an authority over people which was quite remarkable. Their dress and their air of detachment from ordinary worldly matters made them formidable people. Even out in the streets as they walked in pairs to and from school, or on went on rare shopping excursions, they made many folk uncomfortable enough to give them a wide berth, or even cross to the other footpath. People seemed not to know how to talk to nuns when they appeared in their full regalia half a century ago.

Sister Agatha with her class at St Patrick’s Primary School 1956.

At St. Pat’s the student had to learn to talk to nuns. They were nearly always very strong teachers who demanded hard work from their charges and a respectful discipline as well. Classrooms were well-ordered, inkwells and desks regularly cleaned, homework daily inspected, reading skills heard often, and a general atmosphere of busy-ness promoted. Nothing seemed to escape Sister’s notice. Sister herself was under some pressure too. At that time inspectors came periodically to examine the work of pupils, and at St. Pat’s there were two inspections, one from the Catholic authorities, and one from the State. These kept Sister on her toes so that the class would be well drilled for the inspectors’ visits. Then there were the times when she had to have her class up to scratch for receiving First Communion or Confirmation, occasions of further examinations, in the latter case in preparation for the visit by Archbishop Mannix, at that time a revered and dominating figure. It was little wonder that the nuns were strict and not beyond dealing out whacks with a stick or a strap.

Primary education in the forties was heavily laden with the three R’s and St. Pat’s was typical in its curriculum. Spelling and dictation from the old monthly School Paper, or the Victorian Reader, were daily tasks. Writing was taught by transcribing into a copy book, while arithmetic meant daily sums copied off the blackboard or set from Whitcombe and Tombs text books. The learning of Catholic religious beliefs and practices was a break from the three R’s, while Nature Study, History and Geography seemed to come as a type of ‘treat’ when all the tedious things had occupied most of the day.

Sport in an organised way was not very common at the St Pat’s of the 1940’s. Mostly there were casual pick-up games of cricket and football with a rare match being umpired by a parent. Girls played basketball under the nuns’ coaching and often played other schools. But playground activities were more often the skilful inventions of the pupils. There was the marbles season where ‘ringers’ or ‘trackers’ amused countless yardfuls of schoolboys. There was also a cherry bob season late in the year. Boys saved the pips from the cherries and painted them with ink. They then played gambling games where the cherry bobs were won and lost in different ways. The enterprising lads were the ‘bookies’ who would stand astride a small hole in the ground near the school wall. Other boys would stand some paces back and throw their cherry bobs at the hole. The owner of the hole gave odds for a successful throw which went into the hole. ‘Two and your old girl back’ was a popular call. More often than not a miss would be pocketed by the ‘bookie’. Others had small spinning wheels, hand held, called Toodlem Bucks, which they had marked out in segments representing different race horses of the day with varying odds to be paid if the pointer ended in that segment. After each spin, made by pulling the string wound on a cotton reel attached to the wheel, the ‘bookie’ would pocket the bets on unsuccessful segments of his wheel. Endless arguments over cherry bob and marble losses dominated the playground. Girls played many variations of hopscotch and skippy and both sexes had packs of swap cards of all types. These were won and lost in games where cards were flicked towards a wall, with the winner being the one closest to the edge. It was also the era of comics which were read and swapped by nearly everyone.

In the forties St.Patrick’s had no regular tuck shop. Over the road were two milk bars. One, Roach’s, was patronised by the Catholic pupils while on the other corner Blake’s shop was used by the State School students. No-one knew of any rule about this division of custom. It was a type of tribal territory thing, born of tradition and some bigotry, like the name-calling and stone fights across Rogers Street after school.

At St. Patrick’s excursions were rare and the main extra-curricular event was the annual school ball, or concert, where the classes all did an act, whether it be a stage item, or a dance set where boys were made to dance the Pride of Erin, or suchlike, with an allotted partner.

In the forties most pupils still left after Merit Certificate in Year 8. A minority of Catholics went on to a secondary college which usually meant another nuns’ school for the girls or a Brothers’ college for the boys. Co-education was a State High School thing at that time. Mentone had become a centre for schools. The Catholics had St. Bede’s for their boys and Kilbreda for the girls at secondary level, although both took primary students as well in a sort of elitist competition with the parish school.

Tower of Kilbreda College 1996. Photograph by John Madge.

Catholic Secondary schools in the forties had even stricter discipline than the primary ones and Mentone’s colleges were no exception. Here the student met a variety of teachers as subjects changed each forty-minute period. There was the need to confront the mysteries of algebra, geometry, Latin and French as well as the Brothers and Sisters who had made specialties of these courses so that they taught them with ferocious zeal. In boys’ schools there was a lot of corporal punishment, some of it fairly brutal. The cane and a variety of straps and rulers were used on hands, legs and buttocks, while the occasional whack over the face with the teacher’s hand was well-known. Much of this punishment was dealt out as a matter of course to students who had not learned their work, or who could not learn their work. Many students of that era remember the atmosphere of fear that the classroom was known for.

Despite this, a small group succeeded in the Matriculation and Leaving exams and passed on to university or other professional careers. Kilbreda and St Bede’s were proud of their roles in getting Catholics into these higher social places because at that time the Church felt isolated and intimidated by what was seen as an Anglican and Protestant Establishment. However, the majority of students left after year 8 or 9 and went to an apprenticeship or one of the plentiful jobs available at that time.

Leo and Mary Gamble in school uniform of St Bede’s and St Patrick’s schools 1947. Note school bags.

Uniforms were strictly policed with boys forced to wear school suits and caps, while the girls had even more restrictive garb with hats and gloves mandatory. The girls endured a disciplinary approach that was not so physical as that in Brothers’ schools, but just as intense. The nuns tended to be puritanical and emphasised a rigorous sexual morality. This was all right in intent, but it often went to extremes and invited scruples to take the place of a healthy growing up. For example, Kilbreda girls were punished for even talking to boys in the street after school! And to be seen in short dresses at tennis, or shorts at the running track, was unladylike and bordering on the immoral! The annual College Balls run by St. Bede’s and Kilbreda in these years were vastly different to today’s youth functions. At the City Hall in Mentone the students would line up with boys in school uniform and girls in very modest ball dresses. The nuns were not permitted to attend the balls in the public hall but Brothers and parents would be there to ensure circumspect behaviour, while the band played much the same dance music as would be heard for an adult function. Fox trots, modern waltzes and the barn dance brought the sexes together, many in the shyest possible manner. Smoking and drinking were practically unheard of among those at these dances, and most of the girls would go home with their parents at the end of the night. Any slight misdemeanour or over-familiarity was subjected to discipline back at school and the most that students did after the ball was dream!

At secondary level religious education and ritual occupied as much time as in the primary school because the Brothers and Sisters prepared students to face what many considered to be a hostile secular world. Students were taught gospel values but they were also taught to defend the Catholic religion against atheism and what some saw as the errors of other beliefs.

Sport was pushed relentlessly in Catholic Colleges, especially for the boys. Catholics had generally grown up with the inherited Irish complex that they had been treated as inferiors by the perceived ‘establishment’. Whatever the truth of this, it meant that the Catholic was out to show the world that he or she was not second-class and could match it with anyone. Sport provided a way of doing this. Fierce competition both within the school and against other colleges produced some excellent teams and individuals. Success against High Schools or other private schools was particularly satisfying for Catholics, especially the various Brothers’ Orders. But there were also some bitter rivalries among the Catholic schools from different suburbs and the contests were not always sportsmanlike. Some country colleges, especially at Kilmore and Ballarat, guarded their sporting records with unmistakable Irish vigour. St. Bede’s was a willing participator in all this tribal rivalry despite being a small school and usually on the receiving end of some heavy defeats in the forties. It put up some notable good fights, though, and the successes were occasions of great jubilation and a night at the Mentone Picture Theatre for the boarders. Kilbreda was also very competitive at tennis and netball, though one suspects the competition was carried on in a more civilised manner among the girls.

In amongst all this maelstrom of competitive spirit and religious fervour could be found a core of educated and sensitive people who made it possible for the schools to produce some fine results. Many Catholics made a mark in university and professional life after the grounding received at this time, and many others moved into the world to become the parents of a new generation which has adopted a less rigid view of how to live as a Christian.