Caulfield Tragedy: Trauma for the Railway Men

Damaged trains from the Caulfield Disaster. Reproduced with the permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Record Office Victoria, Australia.

After the railway accident at Caulfield station in which three men died and many individuals were injured, the Prime Minister of Australia expressed his deep condolences to those affected by the tragedy. In his press statement he said, “I should like to offer my deepest sympathy to the relatives of the deceased. The whole community feels for them in the sudden and painful losses which they have sustained. To all the injured, I extend my warmest wishes for a speedy recovery.” [1] An Oakleigh bound train had crashed into the rear of a stationary Carrum train at the Caulfield station. The three men who died were from the Chelsea district and of the twenty four who were hospitalised, half were from the Chelsea area. [2] [See Sellers, T., Carnage and Courage at Caulfield] A pall was casted over Chelsea district when the news became widely known. However, the tragedy also seriously affected the railway men involved.

Driver Henry Mummery was in charge of the Carrum train from the time it began its journey from Williamstown. It was there that he set the red lights on the rear motorvan for the journey to Flinders Street station. On arrival at Flinders Street station the 5.57 p.m. Carrum train quickly filled. Like everyone on the packed train, Mummery was keen to return home where he lived in Hemming Street, Dandenong. The day had been exceptionally wet with the city experiencing a downpour of torrential rain in the afternoon. [3] And without any windscreen wipers, it had been a rather trying day for the twenty five year old veteran of the Victorian Railways Department, the last two and a half years as a motorman. At the rear of the train standing on the platform beside the guard’s van was Horace Stubbs of 14 Tamar Grove, Oakleigh. He was watching intently on the signal to give Mummery the all clear to depart.

The electrification of the metropolitan railway network between 1919 and 1923 saw the number of passengers carried increase from 97 million in 1918 to 156 million in 1925 when the last of the all steam trains were phased out. The public was delighted with the new Tait cars which were clean, comfortable and convenient. They were a familiar fixture of the network until the early 1980s. The ‘red rattlers’ as they were more affectionately known, while seeped in romance and reminiscences were not renowned for their robustness.

The confidence of the travelling public, which was a factor underpinning the increased patronage, was dependant on the safety of the network. Since electrification, there had not been a single fatality. Indeed, no loss of life had occurred since three tragedies in the space of four years – Sunshine (1908), Richmond (1910) and West Melbourne (1912). But this was in another era of travel, before improvements to the signalling system were implemented. Still, the system in 1926 was far from failsafe with sections of the network still to be upgraded to the automatic ‘trip’ system. The ‘trip’ system virtually removed the occurrence of driver error by cutting power to a train that entered a section against a signal thus avoiding a potential collision.

Trip mechanism to change signal to danger after passing of train. Courtesy Newspaper Collection. State Library of Victoria.

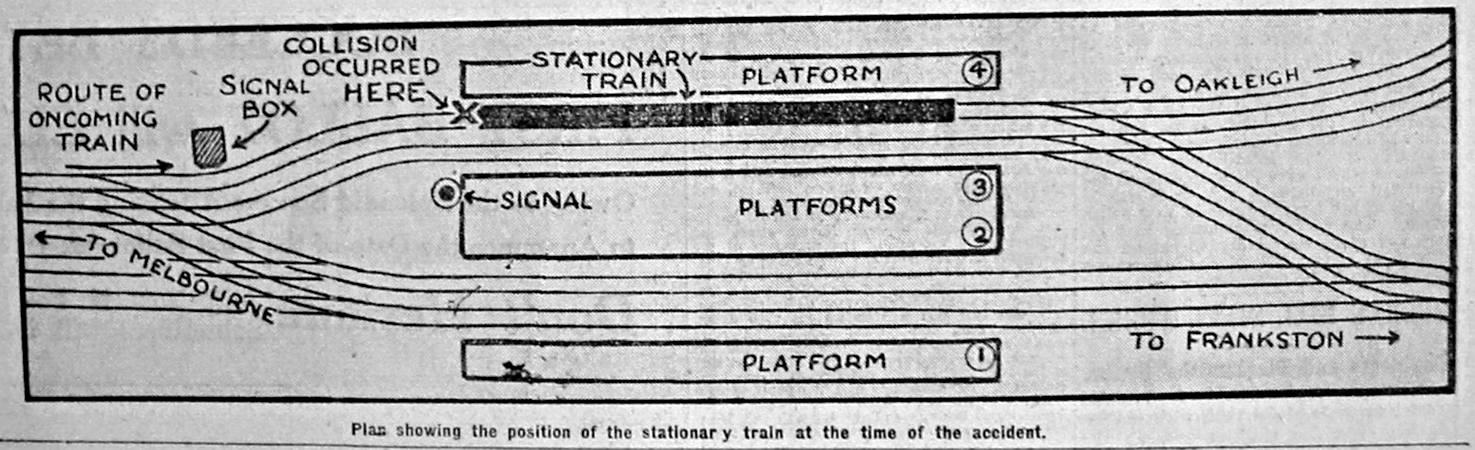

All the automatic signals on the local line were protected by the ‘trip’ system except the last signal before arriving at the Caulfield station from Flinders Street. [4] This particular signal was manually operating from the signal box at the Caulfield Railway station. Signal boxes were an ubiquitous but vital feature of the railway network acting like police directing traffic at a busy city intersection.

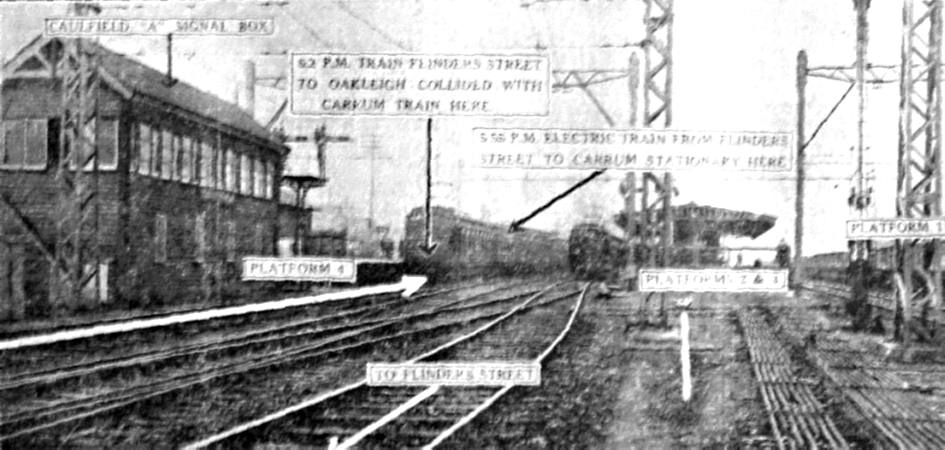

Shortly after commencing duty at 3.00 p.m., Signalman George Wright tested the signals at the Caulfield ‘A’ signal box which was located adjacent to Derby Street, 70 feet (21.3 m) from the Melbourne –up side of platform 4. Wright found the signals to be in proper working order. [5] As the signalman in charge it was his duty to work the multitude of manual levers that controlled the tracks and signals and to synchronise his actions with ‘B’ signal box on the Dandenong downside, south of the central platform. Wright was an experienced and dedicated signalman. He joined the Railways department in 1901 and for the last thirteen years had been stationed at Caulfield. [6] He knew the operation of the Caulfield signals like the back of his hand.

Also on duty on the night of May 26 was John Loftus. Loftus’ role as block recorder was to book the arrival time and destination of each train, leaving the operation of the signals to Wright. [7] For both Wright and Loftus, the afternoon shift was difficult and demanding as it included the busy peak hour service under the fall of darkness. You couldn’t ask for a more experienced and dedicated signalman in charge.

The journey for Driver Mummery and his passengers was like any other, uneventful and unremarkable. After departing Richmond, the signalman at South Yarra directed the Carrum train to the northern local lines. Normally, the train would have travelled along the southern through lines, stopping at platform 2 at Caulfield, but on this day, Mummery’s train was diverted to the local lines to make way for the special race trains from Aspendale. From South Yarra, the train departed at 6.04 p.m. [8] and encountered a slight shower at Armadale that spotted Mummery’s screen though it lasted only a short time. Then it was on to Malvern, the last stop before Caulfield.

Diagram of Caulfield Disaster showing platforms, tracks, signal box and stationary train. Courtesy Newspaper Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Improvement to railway regulations greatly assisted the task of the motorman. Like road speed warning signs, there existed coasting boards, so placed at certain points between each station to assist the train driver with attaining a safe speed thereby avoiding the need to apply the brakes suddenly at the next station. Once a train reached the board, it could safely coast along under its own momentum before the driver gently applied the brakes.

After receiving the starting signal from the guard, Horace Stubbs, for the all-clear to depart from Malvern, Mummery moved his controller to the full parallel position, leaving it in position until the train reached the coasting board some 2,074 feet (632m) from the Malvern platform. Passing an automatic signal a warning bell was sounded in signal box ‘A’ where Signalman Wright gave clearance to Mummery in the Carrum train to travel along Track 6 into Platform 4. After arriving at 6.15 p.m. it waited there for clearance from signal box ‘B’ before proceeding to Glenhuntly.

The delay was caused by a train from Oakleigh which was designated to depart from Platform 3 at 6.20 p.m. As all Frankston bound trains on Track 6 had to cross the path of trains from Dandenong and Oakleigh, delays were inevitable. Up in signal box ‘A’ all eyes were on the lights in the direction of Malvern when the warning bell rang and the dial of enunciator darkened. [9] It was the 6.02 p.m. train to Oakleigh. Moments passed but still the Carrum train was delayed waiting for the up train from Oakleigh to arrive at Platform 3. It wouldn’t be long though before Stubbs, standing on the platform with his light, would give the all-clear, so Mummery released the brakes. It was to be a fatal move.

“The train has passed the stick!”, cried Wright to Loftus. In signal box ‘A’ both Wright and Loftus rushed to the window to alert the driver in the hope of avoiding a collision. As Loftus crossed his arms above his head to denote ‘stop’ he could see the face of the shaken driver applying the emergency brakes as the train continued past the signal box around the curve on to the No 6 Track. Wright ran to the other end of the signal box with the red emergency stop light. But it was all in vain. The red lights of the Carrum train were in full view and a crash was inevitable within seconds. [10]

On Platform 4, Stubbs, the guard of the Carrum train, heard the approaching train braking heavily and turned round to a sight that he never thought possible. [11] It was a sight that caused a rush of adrenalin and he felt helpless to do anything. Somehow, somewhere, he thought a mistake had been made on the supposedly infallible signal system, and as a result he was about to witness the first disaster of Melbourne’s electrified railway system. It was just before 6.20 p.m.

View of Caulfield Railway Station showing platforms and tracks. Courtesy Newspaper Collection, State Library of Victoria.

The luckiest person to escape the impact was the driver of the Oakleigh train, William Stevenson Milvain. Structurally, the cabin of the front motorvan withstood the shock and suffered only minor damage and Milvain was not badly hurt, but he was flung against the side of the cabin, and suffered severely from shock. [12] He may have had a lucky escape, but the worst was yet to come. Life would never be the same for the veteran with an impeccable thirteen year record as an engine driver. Milvain was conscientious with a reputation as an extraordinarily careful driver. [13] He took his responsibilities seriously and often reported defective signals. In the township of Frankston where he lived in Dandenong Road, he was held in the highest esteem. On one occasion at a level crossing a short distance from the township, he brought his train to a dead stop in order to prevent a collision. [14] But Milvain felt the pressure that came with driving electric trains. He suffered from a neuralgic condition and his eyes would often cause him trouble while driving as a result of seeing red below a green signal. To help with his condition, Milvain’s consulting physician, Dr J MacKeddie whom he last saw fourteen months earlier, had prescribed some treatment to relieve the symptoms. [15] And so Milvain soldiered on adding further to his thirty eight years with the Victorian Railways Department.

The Oakleigh Train showing damage to the driver’s compartment. Reproduced with the permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Record Office Victoria, Australia.

The trauma associated with the disaster was to continue for the railway men. Enquiries were to take place in an attempt to establish when, how and by what means the three casualties of the crash met with their death.

Footnotes

- The Age 28 May 1926 p9.

- Friends of Cheltenham and Regional Cemeteries Inc. (comp)., Biographical Register of the Caulfield Railway Disaster 26 May 1926 (2008) p iv.

- The Argus 27 May 1926 p9 and The Age 27 May 1926 p10.

- The Argus 24 June 1926 p12.

- The Argus 25 June 1926 p11.

- The Herald 27 May 1926 p1 and Rutledge, C. L., Caulfield 26 May 1926 printed in Somersault magazine Vol 25 No. 2 page 24.

- The Argus 23 September 1926 p9.

- Rutledge, C. L., Caulfield 26 May 1926 printed in Somersault magazine Vol 25 No. 2 page 24.

- The Argus 25 June 1926 p11.

- The Argus 23 June 1926 p19.

- The Age 27 May 1926 p10 and The Argus 24 June 1926 p11.

- The Sun News-Pictorial 27 May 1926 p3.

- The Argus 28 September 1926 p13.

- The Herald 27 May 1926 p1.

- The Argus 28 September 1926 p13.