And So Ends the Story of the Caulfield Railway Disaster

Damage carriages involved in the Caulfield Disaster, 1926. Reproduced with the permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Record Office, Victoria.

On Tuesday June 22, 1926 a Coronial Inquest into the Caulfield Railway Disaster was commenced by Coroner Daniel Berriman, before a crowded court. He had the assistance of Dr Ellis. Specifically the court was to inquire as to when, where, how and by what means George Leonard Dudley Beames, William Dobney and Arthur James Beresford Upton met with their deaths on the night of Wednesday 26 May 1926, when an Oakleigh bound train crashed into a stationary Carrum train at the Caulfield station. See Sellers, T., Carnage & Courage at Caulfield, Kingston Historical Website and See Sellers, T., Trauma for Railway Men , Kingston Historical Website.

Mr MacFarlane representing the Victorian Railway Commissioners was instructed by the Crown Solicitor. Mr Edwin Corr of F Brennan & Co appeared on behalf of the Australian Federated Union of Locomotive Engine Drivers representing Mr William Milvain driver of the Oakleigh train. William Slater represented the interests of Signalman George Robert Wright. Mr Foster appeared on behalf of the Oakleigh train guard James Hargreaves. [1]

Coronial inquests were, by law, a necessary function of the justice system. The majority of cases involved routine deaths and were dealt with expediently. But once in a while there came before the Coroner a high profile case that was widely covered by the media.

In the 1920s, coronial inquests were merely required to find the cause of death and whether there was sufficient evidence for charges to be laid. Unlike the role of the Coroner today, the focus was apportioning blame, not on making recommendations for improvements. As a reflection of the era, the Railways department and the presiding government had no reason to fear an adverse finding. They were above the law. But the same could not be said for William Milvain, George Wright and James Hargreaves. Their only hope of escaping an adverse finding and potential criminal charges was that the accident occurred as a result of a fault in the system.

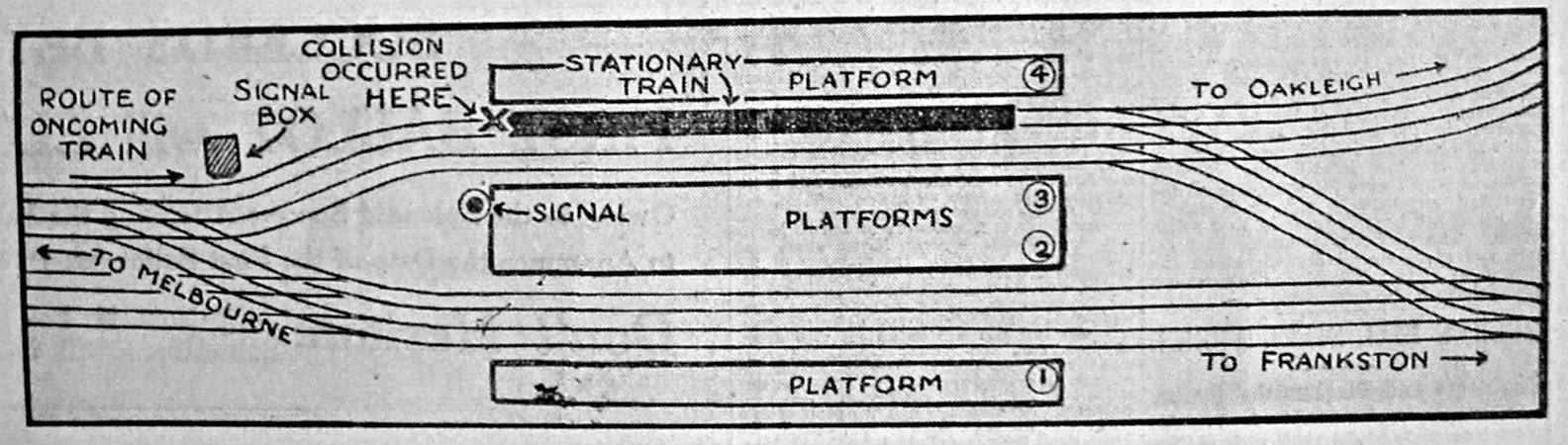

For Coroner Berriman, the Caulfield Railway disaster was one of the most difficult and challenging that had come before him. The evidence was highly technical and occupied his attention over much of the three day inquest as he pored over the technical diagrams of signals and tracks, blue prints and plans, with the help of a powerful magnifying glass. The plans were baffling to all but the experts trying to make sense of the intricate maze of tracks showing the relative position of signalling boxes, apparatus and posts. [2]

Also before the Coroner were a mass of witness statements, reports and results from tests carried out, interviews and enquiries made by the railway experts as well as the police. Of the many reports before Berriman one was of an inquiry conducted by the Railway Department. It reached a number of conclusions;

- The Oakleigh train was examined and no mechanical faults could be found. On the day of the tragedy, both William Milvain, and William Satchwell who had charge of the train before Milvain, found the operation of the brakes to be satisfactory.

- The signal system was in perfect working order when tested on the night of the accident; and

- The Oakleigh train had been travelling faster than what Milvain had made out in his statement. [3]

The verdict had already been reached before the coronial inquest had even begun; the report had effectively concluded that the disaster could only have been caused by Milvain passing the signal at ‘danger’.

The first two days were dominated by evidence heard from various railway experts – signalmen, fitters, inspectors and artisans. The focus was the signal on home semaphore (post) 1 and whether the system could be manipulated to change the signal from ‘danger’ to ‘proceed’, either deliberately or accidentally, while the Carrum train was waiting at platform 4. Much of the evidence given at the inquest focussed on the signalling system.

Four witnesses testified they saw the home signal at ‘danger’ immediately after the accident. The guard of the Carrum train, Horace Stubbs, gave evidence on the second day that as the first two cars of his train passed the home signal, he saw the signal go back to ‘danger’. [4] Crucially for the defence team, there were no witnesses who saw the home signal immediately before the Oakleigh train passed semaphore post 1.

The other possible cause of the tragedy was a failure of the signalling system on the night. At 11.00 pm., a goods train was arranged to travel along No 6 road past platform 4. The test showed the signals to be working perfectly. [5]

Diagram showing the position of the stationary train at the time of the accident. Courtesy Newspaper Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Lawyer Edwin Corr ended the second day of the hearing on a positive. His defence of Milvain was that the disaster occurred from a failure of the Railways Department to provide adequate protection. Milvain had made a basic human error, and the lack of safety provisions allowed the tragedy to occur. However, by the end of the second day of the inquest, the evidence was conclusive that the track-lock installation which protected the signalman was working and while a train was at platform 4, there was no way the signal could be changed to ‘proceed’. It was proved beyond reasonable doubt that the home signal was against the Oakleigh train. It was at ‘danger’ the whole time.

On the last day of the inquest, the focus had switched from the signals to the actions of Milvain and Hargreaves. On the advice of their counsel, both elected not to take the stand and their statements were read to the court by Senior Detective Bruce. Both gave corroborative evidence that the home signal was a ‘proceed’. On 9 June, Milvain stated that he closed the controller about 140 yards (128m) before reaching the coasting board and when he passed the signal, the train was travelling at 20 to 25 miles per hour. After seeing a red light which he thought was on the No 5 road, he applied the emergency brakes. [6]

The weight of the evidence was overwhelmingly against Milvain. On 4 and 9 June, Superintendent Albert Stamp conducted a series of three experiments with a test train. The train resembled the Oakleigh train on the night of the tragedy as close to as possible. The conclusion from Stamp’s tests was that Milvain had been travelling faster than the statement given to Senior-Detective Bruce and that the presence of the Carrum train should have been noticed well before he applied the emergency brakes. [7]

Corr in addressing the Coroner urged him ‘not to accept the infallibility of the mechanical signalling system against the evidence of two men whose records are extremely good. [8] Stubbs, the guard of the Carrum train, had sworn that he saw the home signal go back to danger after his train passed it. Yet it was most unusual for a railway guard to have looked back and to have watched the signal change. In some inexplicable way that signal may have changed.’

Foster speaking on behalf of James Hargreaves said, ‘Your Honour, a guard’s duties regarding signals were only part, and a secondary part of many duties. It was not unreasonable to believe that with Milvain driving, and many other duties to attend to, that Hargreaves got down from his guard’s seat and attended to those other duties. In that case, could it be said that Hargreaves was guilty of gross and wilful negligence?’ [9]

The Coroner in his verdict said, ‘The functions of a coroner are, in my opinion, akin to those of a justice acting in a magisterial capacity with regard to a charge that can only be tried by a jury. The weight of evidence is certainly against the driver in a more serious degree, and perhaps to a lesser degree against the guard. I find that deceased died from injuries received in a collision between two electric trains at Caulfield on May 26, and I find William Stevenson Milvain and James Hargreaves guilty of manslaughter in the first degree, and direct that they be tried at the Criminal Court on July 15.’ [10]

After a number of delays that only heightened their worry, the accused faced Justice Frederick Mann and a jury in the Criminal Court on 21 September 1926. [11] Much of the same evidence presented at the inquest was heard. For the charge of gross negligence to be sustained, the jury had to be satisfied that Milvain and Hargreaves had shown such a want of care in critical circumstances as to merit punishment. As Justice Mann told the jury, there was no punishment for having failed to exercise the very highest degree of vigilance. All that was required was for the defendants to show that at the critical time their attention had been distracted which caused either of them to make a real and honest mistake, something that was called an error of judgement. The jury took just seventy minutes to return a verdict of not guilty with the following rider:

‘In the opinion of the jury, from the evidence given regarding the running of electric trains, the precautions taken to safeguard the public at this particular point are inadequate, and should be rectified immediately.’ [12]

On the last day of the Criminal trail, another case was also reaching its conclusion at the County Court before Judge Williams. Lillian Halfpenny was suing the Railway Commissioners for £499 damages through her father, John Halfpenny. The Commissioners accepted liability but offered only £75 in compensation which was refused and the matter went to trial. The jury heard that when the crash came Halfpenny’s two legs were caught and before she could be released, a great deal of woodwork had to be cut away. She received injuries to both heels and to her knee which the jury was told might always affect her. Halfpenny had also suffered hearing loss in one ear by one third and had never been in good health since the accident. She slept badly and was having nightmares. Halfpenny had also lost her job with Currie and Richards. After paying her half salary for a considerable time, she received a letter signed by Sir William Brunton expressing regret that the company was unable to keep her position open. The jury returned a verdict for Halfpenny and she was awarded £287/13/-. [13]

Back to the aftermath of the Criminal Court trial. If Milvain or Hargreaves had been found guilty, there is no doubt the matter would have ended there. But, the lives of three persons were lost and many more injured and someone had to take the blame. Milvain’s career was over and regardless of the verdict, he would never drive a train again. Hargreaves also resigned. Instead, the jury had given the Railways Department a slap on the face. It was the beginning of a political furore for John Allan, the Premier of Victoria, and his Country-National coalition. John Allan was a man of the land in the conservative mould, described ‘as a hard fighter but a fair opponent, with a genial, imperturbable disposition’. [14]

In September 1925, the Attorney-General, Sir Frederic Eggleston, declared that he would not permit a man charged again for an offence of which he had been proved innocent. So what was the Allan Government to do when the Railways Commissioners issued a summons to Milvain and Hargreaves to appear before a board of discipline arising out of the same incident for which they had been found not guilty? There was no simple solution. The Allan Government decided to uphold the independence of the Commissioners and weather the political storm by arguing that the morale and discipline was paramount to the public confidence in the railways. Milvain and Hargreaves would answer the charges for misconduct before the board. The charges for breach of regulations under the Railways Discipline Act were:

- Permitting in circumstances not included in any of the exemptions of 60B, the train to pass a home signal at danger, contrary to regulation 60B.

- Failure to observe carefully the signal or signals, contrary to regulation 167.

- Failure to keep a good look out when the train was in motion, contrary to regulation 171a; and

- Failure to pay immediate attention to the signal or signals, contrary to 171B. [15]

The decision to charge Mulvain and Hargreaves before the board of discipline roused the ire of both the Labour Party and the Railways Union who argued they were being made scapegoats. It was arguably the biggest political issue of October 1926. In the Legislative assembly, session after session saw Edmond (Ned) Hogan’s Labour opposition maintain their rage towards the Government and were at times supported by members of the Allan coalition. The debate was lively and at times heated.

If found guilty before the Board and dismissed, Milvain and Hargreaves would be deprived of their benefits due under the Railways’ superannuation scheme. While the outcome of the hearing is not known, the Allan Government paid a high price and relinquished power to Hogan’s Labour Government in May 1927. As for Milvain, born in 1867 in Macedon, Victoria, the son of John Milvain and Thomasina nee Wilson, he died at Frankston in 1939 aged 73. [16] One basic error had blighted an otherwise outstanding career with the Railways.

The Caulfield Railway disaster remains to this day a significant event affecting so many lives from Melbourne’s south-east. Three lives were lost and as many as 173 were injured. And it should never have happened. For such a simple error to have caused such widespread carnage shows that the Caulfield signalling system was inadequately protected. Milvain’s error was further compounded by the obscured view of the driver travelling along the local line who could not positively see a train on the No 6 track until he was within 360 (109l.7m) and 470 feet (1243.2m) from the station.

Milvain may have caused the accident, but he wasn’t responsible for creating it. He was no less culpable than a driver who hit a pedestrian at a level crossing without adequate protection. The Railways Department and its officials contended at the inquest and criminal trial that the Caulfield junction was not dangerous. And they didn’t change this position. It was to be another seven years before the ‘trip’ system was installed at Caulfield eliminating the dangerous ‘black spot’.

Interior of damaged carriage involved in the Caulfield disaster. Reproduced with permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Record Office Victoria.

Footnotes

- The Argus 23 June 1926 p19.

- Ibid.

- Report by Albert Stamp, Superintendent of Locomotive Running, VRD. VPRS 30/P/O Unit 2143 File 464.

- The Argus 24 June 1926 p11.

- The Argus 23 June 1926 p19.

- The Argus 25 June 1926 p11.

- Report by Albert Stamp, Superintendent of Locomotive Running, VRD. VPRS 30/P/O Unit 2143 File 464.

- The Argus 25 June 1926 p11.

- The Argus 25 June 1926 p11.

- The Argus 25 June 1926 p11.

- The Argus 22 September 1926 p9.

- The Argus 29 September 1926 p21.

- The Argus 28 September 1926 p13 & 29 September 1926 p21.

- J. B. Paul, 'Allan, John (1866 - 1936)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Online Edition http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A070038b.htm

- The Argus 20 October 1926 p25-26.

- Genealogical research by Jenny Coates, BA(Hons), family historian.