Moorabbin Civic Centre

City of Moorabbin New Council Office Building, c1990. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

With the population and industrial growth of the City of Moorabbin in the 1950s the number of council officers needed to provide appropriate services also increased. With this increase came the demand for office accommodation where assigned tasks could be completed successfully. The main location of their office activities was a red brick building erected in the 30s. Additions were made on the South Road side in the 1970s but with even these additions the problem of overcrowding persisted. One architect described it as a “veritable rabbit warren” while a councillor suggested too much of officers’ time was devoted to assisting visitors navigate the maze to find the appropriate individual who could answer their concerns. [1]

While tentative efforts were made in the late 50s to acquire land to build a Civic Centre and some money later spent commissioning architects to prepare preliminary plans, it was not until 1976 that a proposal to extend the town hall was revealed to the public. The proposal, first published in the Moorabbin News, was described as a bombshell and generated angry responses from some councillors and ratepayers. Cr Blackburn was adamant in his opposition commenting that he couldn’t see himself committing ratepayers to additional expense “simply to supply offices for semi-government departments.” [2] For him such facilities were a luxury when basic works of drainage and street construction remained to be completed. Blackburn believed the city had passed the peak where its development needed planners and administrators. For him the need for such facilities was diminishing not increasing. [3]

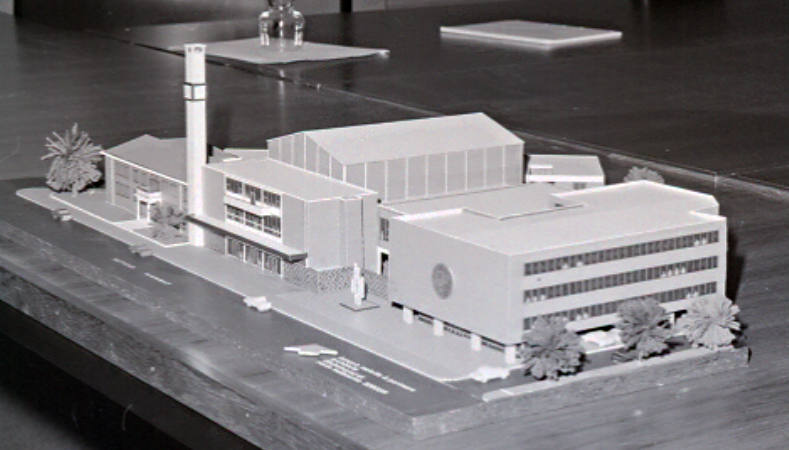

Architectural model of proposed extension to town hall, 1976. Courtesy Leader Collection.

Other councillors expressed surprise at the proposal. Cr Duckmanton was astounded and wondered from where the authorisation originated for the development of such a proposal. Some councillors declared they were uninformed about the existence of the proposal. In response, the town clerk, J Waters, produced a series of minutes which clearly showed the plans were authorised by the full council in January 1976. A fiery debate followed but only two councillors, Blackburn and McHutchison, stood against the proposal and both were facing an election the following Saturday. [4]

The architectural firm, James H Melville & Partners, commissioned to prepare the model for the extension to the town hall, was caught up in the controversy. They complained that their involvement had been publicly presented in an unfavourable and untrue fashion. They pointed to comments of councillors published in the local paper reporting ‘considerable shock’, ‘surprise’ and ‘opposition’. Yet they received a letter from the council officially appointing them as architects on February 3, 1976. “We are alarmed that our firm is presented to the City and ratepayers of Moorabbin as being secretive and conniving in an attempt to force unnecessary expenditure and for decisions for which no authority had been given.” [5] Cr Stevens, a constant supporter of the project, moved a motion in council which acknowledged that the architects had carried out the instructions received from council in a satisfactory manner and that the council had the utmost confidence in the integrity and professional ethics of the architects. In addition, the council regretted any statement made either by an individual or the council as a whole which reflected upon the honesty and professional integrity of Melville and Partners. [6]

The next year an announcement by the Country Roads Board that they intended to widen Nepean Highway caused a review of the town hall extension plans. The widening of the highway from Elsternwick to South Road was about to commence and road widening was also planned in front of the town hall and along to the railway bridge to facilitate traffic flow. With this development access to the town hall would be impeded. Given this situation the concept of an administration facility attached to the town hall was once again questioned. As an alternative location the deputy engineer, Ian Anderson, suggested that the Grange site, purchased in 1973, be used as there was space there and it was close to public transport. To help resolve the issue the council decided to commission a feasibility study which examined the two sites. Specifically the study aimed to explore the egress problems associated with the current site, and the feasibility of acquiring further adjacent properties for the siting of an administration block, or for reorientation of the block with appropriate entry and car park facilities. In addition it was to examine the use of the land known as the Grange. [7]

In December 1984 the council announced its intention to build a $5 million administration complex on the Grange site. [8] But not all councillors were in agreement with the decision, arguing instead for the construction of the centre on the existing town hall location. Acrimonious debate followed. After Cr Levy informed his colleagues that there was a covenant on the Grange site, which prevented the construction of the administration centre there, some councillors had second thoughts about the Grange decision. Levy stressed that he unequivocally supported the necessity of up-grading the administrative building but only on its present site. By April 1985 concern was being expressed about the lack of progress in resolving the argument about the site of the new building. Staff in the meantime were working in cramped conditions, in small open planned offices. Partitions were erected in some areas but officers still faced problems of noise and lack of privacy. The deputy town clerk, Doug Owens, worked in an open office where he was troubled by interruptions as “it was easy for anyone to walk in,” he said. The city engineer’s department, which employed twenty people facing lack of space, knocked a hole in a back wall to gain access to a newly installed portable office. Cr Le Page said, “It is not good for staff morale to work under these conditions.” [9]

The final design for the new administrative centre was unveiled in April 1986 and Jennings Industries Ltd was directed to commence the preparation of the site. The new three-storey building was to feature a multi coloured, irregular glazed and unusual façade. Internally, large open spaces were to provide for team activities while small meeting rooms provided privacy and individual offices. The basement was to have a two level car park together with storage and records areas. Provision was also made for the mayor’s office, councillor room, two committee rooms, and a council chamber. The old council building was to be refitted as a library, infant welfare centre, hall and meeting rooms for the public. Staff not able to be accommodated in the existing town hall building were to be housed temporarily on the Grange site. [10]

Preparing the foundations for the Administrative Centre, 1986. Courtesy Peter Dack.

After years of haggling over the site and the nature of the building to be constructed, the official ceremony of turning the first sod to start construction was carried out by the mayor, Cr Keith Duckmanton, in April 1986. Demolition of the unwanted buildings on the site began and the excavation of the new car park commenced. [11] The architectural firm of Cocks, Carmichael Whitford prepared the architectural documentation following approval of the concept sketch plans, while consultant engineers, Lobley Treidel Davies, were selected to document and supervise the hydraulic electrical and mechanical services. The structural works were the responsibility of civil engineers, Lovell-Smith Mathieson & Crisp under the supervision of Jennings Project Management. The building was completed within two years at a cost of $10.2 million with internal furnishing being additional costs. Cr Jack Levy officially opened the new building on June 25, 1988 with appropriate ceremony while clad in the mayoral robes of office.

Construction of Administrative Centre in progress, 1986. Courtesy Peter Dack.

Footnotes

- Moorabbin Standard News, March 5, 1959.

- Moorabbin Standard News, July 28, 1976.

- Moorabbin Standard News, August 4, 1976.

- Moorabbin Standard News, August 25, 1976.

- Moorabbin Standard News, September 29, 1976.

- Moorabbin Standard News, November 17, 1976.

- Moorabbin Standard News, April 27, 1977.

- See, The Grange Site, Kingston Historical Website.

- Moorabbin Standard News, April 10, 1985.

- Moorabbin Standard News, April 9, 1986.

- Moorabbin Standard News, May 7, 1986.