Australian Boy Magazine

Remembering the Anzacs.

In the post-war boom, and before television arrived in 1956 to doom their ascendancy, Australian children collected, swapped and consumed comics. They chose from a vast range of American all-picture comic books – reprinted in Australia – or imported English comic papers, which carried both strips and text stories.

Possibly inspired by the immense success of Britain’s revolutionary Eagle magazine, launched in 1950, as well as the long tradition of the Boys’ Own Paper and its ilk, several Australian publishers sought to revive the ‘childrens’ magazine’ concept in a contemporary form attuned to local audiences. In New Zealand, Junior Digest – a digest-sized juvenile monthly in the same tradition – had been launched in September 1945 and was already gaining distribution in Australia.

The first entrant, in 1952, was Boy (later The Australian Boy fortnightly). It would soon be joined by The Silver Jacket, Juniors’ Journal, Junior Telegraph, Chucklers’ Weekly, and the Australian edition of Eagle.

Boy was the brainchild of E J Trait, Managing Director and Editor of Standard Newspapers of Cheltenham, Victoria. Trait was a remarkable crusading journalist and political activist, and his desire to exert a moral influence appears to have been the motivation behind the launching of a quality boys’ magazine.

When it began on 17 October 1952, Boy was styled “a thrill-packed comic-magazine every fortnight”. Priced like a comic, its 28 pages represented good value for eight pence. The first issue contained columns on scouting and stamp collecting, articles about Tasmanian war hero Captain Aubrey Koch and the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch miniature public railway in England, features on how to build a model yacht, improve your photography and develop your drawing ability, and sporting notes. These were interspersed with three short stories and five comic strips.

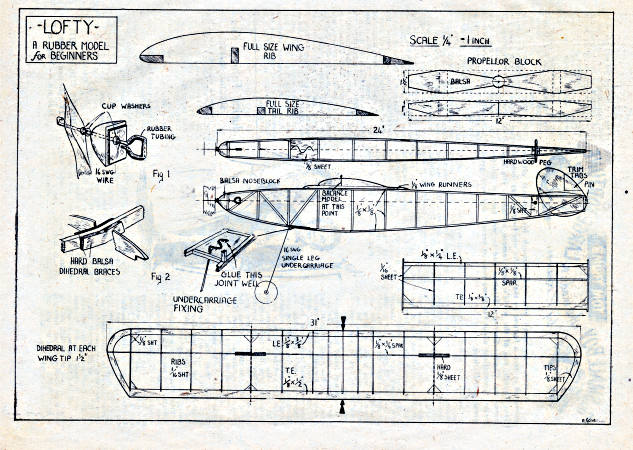

Lofty a Rubber Model for Beginners.

The early, crudely styled covers soon gave way to three-colour illustrations and photographs, depicting boys engaged in hobbies and healthy outdoor activities, such as scouting, cricket, model railways, snorkelling, flying model planes and fishing.

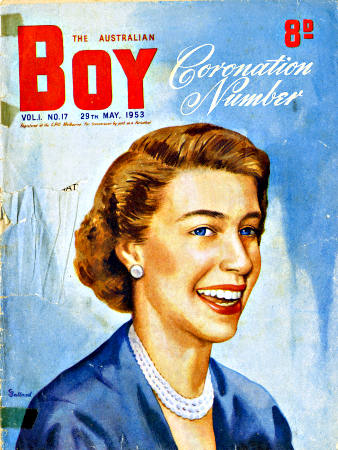

Perhaps the most notable cover, on 29 May 1953, was a specially prepared colour portrait, by Stan Ballard, of the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II - beloved by her antipodean subjects to an extent that today’s young Australians might find hard to imagine. She became one of the few women ever featured in the magazine!

Queen Elizabeth II at the time of her coronation.

David Cooper was a prolific early Boy artist, contributing humour strips starring the tubby seaman, Barney, and a cheeky schoolboy named Bimbo. He also drew serial/adventure strips, including Kilowatt (about an intelligent robot) and Kane of Calder College, about a poor scholarship student, Frank Kane, making his way through an exclusive private school.

He was followed by Dick Davies, whose characters included the cantankerous old Moleskin and Batty & Baloney, eccentric explorers blundering around darkest Africa.

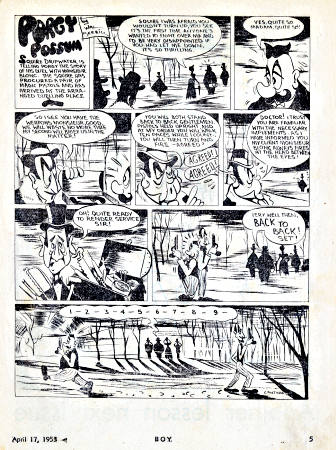

The Adventures of Porgy Possum, by Wal Merrill, was an unusual cliff-hanger serial, with Porgy being summoned by his Uncle Bill to Possum Castle, to retrieve a mysterious and valuable black box from the castle’s secret tower. Disturbingly, Porgy’s intriguing adventures were terminated in mid-air in issue #19, without explanation!

Porgy Possum a cartoon character.

Stan Ballard drew Shorty Long - Deputy Sheriff, an American Western strip, which ran throughout the magazine’s first year. Later, Phyl Dyson illustrated Jackey Jackey, which told the true-life story of William Westwood, known as ‘The Gentleman Bushranger’.

Comics were supplemented by fiction stories, serials and series. Of the latter, the motor cycle racing drama of Des Duckett – The Dirt Track Demon (written by Eric Gunton) and the adventure-seeking sports journalist, McGowan (written by Allan Aldous), were regular features. Hobbies were well catered for, including the long running “Plane Talk”, by Tony Farnan, which explored the building and flying of model aeroplanes.

Among the relatively few regular advertisers were Egginton’s Toy shop, Will Andrade’s Magic Shop, C.O.R Petrol, Paddle shoes and Robilt model railways.

By the time Boy celebrated its first birthday, the Boy Club had been launched. Ultimately its membership would exceed 20,000, and readers were encouraged to wear their club badges proudly. Boy also had its own weekly radio program, Boy Time, on 3AW and 3CV. Readers’ letters and jokes arrived in their hundreds, and a selection was printed in every issue. There was an active pen friend column.

Despite these successes, it had become necessary to introduce serious production economies. The price went up to nine pence, and although the page count was increased to 32, the 3-colour cover was dropped, and other signs of cost-cutting soon became obvious. Poorer photographic reproduction and one-colour covers began to give Boy a faded, dour look which made it less appealing against the brightly coloured comic covers jostling it on the newsagents’ shelves. Nevertheless, the quality of its content and its ideals remained high and resolutely all-Australian.

A cost cutting cover.

Yet the relentless slide continued. With issue #46 the page count shrunk to 24. By issue #65, when it published a 6-page comic strip by “13-year-old Max Gillies, of Caulfield” [was it the Max Gillies, I wonder?], the publisher had resorted to the cheapest means of reproducing comics and graphics - with half-tone photographic blocks instead of normal line blocks. And the editor’s gentle appeals to his young readers to swell the magazine’s circulation had become more insistent:

You will be glad to know that there are over 19,000 members in Boy. Nineteen thousand is a lot of boys and girls, you will agree….now if every one of those nineteen thousand made a point this week of introducing only one new regular reader to Boy, what a boost it would give our circulation! Will you try? As good club members, I know you will.

By the third birthday issue, #79, the page count was back to 32 but the price had risen to one shilling. And the editor was now asking his readers to give Boy a birthday present by tripling the circulation. Perhaps as a symptom of editorial exhaustion, there were strange oversights – like the inclusion in this issue of a purportedly original My Pop comic page which was the virtual equivalent of a photocopy (had such technology then existed) of a particular American Blondie strip, with faces changed.

In any case, this last appeal was too late. A fortnight later, in an “Important Announcement” in #80 (31 October 1955) he broke the news:

It is with very deep regret that we are forced to announce that publication of BOY is being suspended from this issue.

We have had many problems. Our sales were never high enough to meet the high cost of producing a comic of this type. Alterations were made in methods of production – cheaper paper was used, our covers changed from three-colour jobs to one colour – not because we liked these changes, but simply because we were fighting to keep BOY going…

We have made friends with boys in many places – here and abroad. We hope to retain their friendship. But at least for the present we must say goodbye to them and thank them for their loyalty to BOY for more than three years.

Again, thanks, boys (and girls too). We leave you in an unhappy frame of mind.

I can remember how devastating such farewell news was when, one after another, these magazines closed. It left a palpable void in the world of schoolchildren for whom each weekly, fortnightly or monthly issue was anticipated and savoured. And it was to the credit of editors like E J Trait that they were honest with their readers about the economic realities of producing their favourite magazine.

At their best, these were innovative, high-minded and earnest attempts to provide Australian children with a national forum for their own expression, and with quality reading matter: original articles, comic strips, stories, competitions and other features that would stand in stark contrast to the sometimes lurid array which dominated the comic book market, and frequently attracted the concern of educators and parents’ groups.

The production costs of these childrens’ magazines were far higher than for the comics with which they competed, since Australian artists and writers had to be paid to produce original work, and editorial staff had to manage and respond to the flow of readers’ letters and contributions. Yet they had to be sold for the same cover price as comics, in order to attract a viable part of their young readers’ carefully guarded pocket money.

They deserved to succeed. Sadly, their share of the small Australian market place was never large enough to cover productions costs, so most of them had short lives. Yet, even today, those who grew up with them remember Boy and its companions fondly as a strong, shaping influence in their childhood. It was not only the quality and appeal of their contents: for many (including this author) it was also the thrill of seeing your name, and your letter or contribution, in print for the very first time.