Murder at Mordialloc: The Case of Patrick Joseph Duff

Scene of the Murder. Reproduced with permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Records Office, Victoria.

It was late one summer evening in December 1920 when Arthur Ernest Dowling (Ernie), unable to sleep, awoke and found his mother locked in the kitchen of the family home alone with his near neighbour. ‘Who is there?’ the man asked as Dowling banged on the door and tried to break it down. Dowling was told by his mother to go back to bed and as he did, he overheard her saying to the man, ‘My God, Ern knows everything.’ It was not the first time the 16 year old had seen them together when Dowling senior was away. The locked door, muffled voices and his absent father that night only confirmed his suspicions that he mother was having an affair. Dowling took it personally and from that night forward, there was a change in the studious, well behaved and loving son.

The sons of the soil who worked the land along the Wells Road corridor in the Mordialloc-Chelsea district were small scale farmers. Ownership was fluid as their success waxed and waned from season to season such were the hardships they faced farming on land which had been wetlands. In the small community, there resided two families, fellow farmers and friends, the Duffs and Dowlings. Patrick Joseph Duff (1867-1921) was a native of Wexford, Ireland born in 1867 who after his marriage to Esther nee Hawkins (1867-1941) in 1890 emigrated to Victoria on the Cuzco arriving in August. [1] The Duffs would become long-time residents of the Mordialloc district when few lived in the area. Jovial and genial, Pat Duff was described as a quiet, unassuming man who never had an enemy. That was until the night of 2 December 1920 when young Ernie Dowling heard his voice in the locked kitchen. From then on, the 53 year old was persona non grata in the eyes of Dowling.

The Dowling family can be traced back to 1807 with the birth of Samuel Dowling (1807-86) in Wilshire, England. In 1839, Samuel married Marianne (Mary) nee Durrant (1814-81) and after the birth of their seventh and last child in 1853, the family emigrated to Victoria on the Queen of the Seas arriving in July 1858. [2] Their third child was Arthur Fritz Dowling (1880-1965) born at Emerald Hill (South Melbourne) on 21 October 1880. He married Grace Roberts nee Symons (1879-1953) on 30 March 1901 at Fitzroy and they were to have five children; Dorothy Symons (1900-71), Arthur Ernest (Ernie) (1903-73), Frederick William (1905-55) Grace Winiberg (1906-75) and Leonard Edward (1910-96).

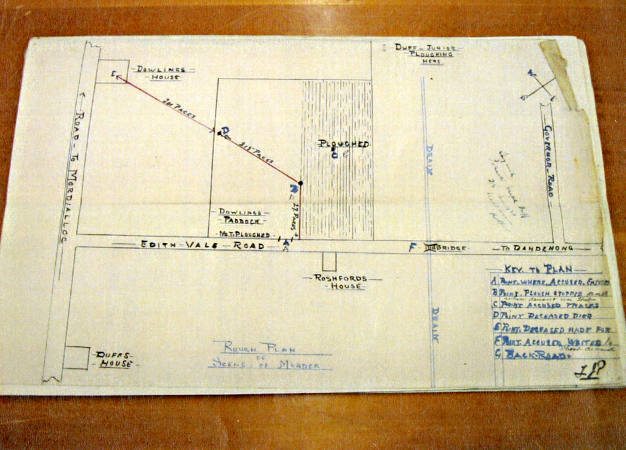

Pat Duff, along with the market and dairy farmers who worked the land along Wells Road, appears to have had mixed success. [3] Between 1903 and 1909, he is listed as a farmer of Wells Road, Carrum. [4] before reappearing in 1914/1915 [5] on the north-west side of Wells and Edithvale roads, on one of eleven farmlets along that narrow strip of land to Governor Road, Mordialloc. Duff was only there for a year before taking up land on the opposite (east) side where there were just three farms: John L Andrews, R Horsley and Pat Duff. There is no record of Pat Duff in the Sands & McDougall directory after 1919. [6] Arthur Dowling is first noted as a dairy farmer occupying Richfield in 1918 after the Duff family moved to the opposite (south) side of Edithvale Road, half a mile from the Dowlings. Further along Edithvale (Springvale) Road to the east was the home of the Rochfords. In the north-west direction could be seen in the distance the Dowling home adjoining Wells Road, while the rear boundary of the property extended just before the main drain not far further east from where the Rochford home was located.

Rough plan of scene of murder. Reproduced with permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Records Office, Victoria.

Ernie Dowling was never the same after the December incident. Towards his mother whom he loved dearly he became bad tempered. On one occasion when Grace Dowling tried to speak to her son about the incident Ernie replied, ‘Mum, don’t speak to me. I don’t want to hear anything about it.’ Perhaps in Dowling’s mind his mother had been wronged and his family’s honour had been impinged. In Easter 1921 it became all too much and the lad ran away. His parents advertised in the newspapers, pleading for him to return home. Dowling wrote a letter home to his brother Fred saying he was sorry to have to leave but it was not due to his childishness. Shortly after he was persuaded by his father to return, but the issue still lingered on his mind. [7]

The whole matter was revived on Thursday 2 June 1921, the six month anniversary of the incident in the kitchen. It was also the eve of the day that Arthur and Ernie were due to travel to Wonthaggi for a job involving chaff cutting. (This followed two previous weeks spent at Cranbourne.) The previous night, Wednesday, was the last straw. Dowling senior was again absent and Ernie had noticed Duff and his mother in the front room alone. And it made him wild. [8]

The events of that fateful day began at the Dowling house in the morning. It was a very windy day with a strong southerly blowing. Having breakfast was Joseph Kinniburgh. He was asked by Ernie for a loan of his bicycle to go to Mordialloc to which Kinniburgh obliged. The labourer had no reason to suspect any enmity between Duff and Dowling. The day before, he saw them having breakfast and dinner together and they both ploughed in the field. Kinniburgh observed them as not very friendly and neutral towards one another but he never saw them have a row. [9]

Reginald Richard Nicholson of Barkley Street, Mordialloc was in the office of his estate agent business Phillips and Nicholson in Mordialloc when young Dowling entered. It was approximately 9:30 a.m. Dowling handed Nicholson a letter from the Sun Insurance Office authorising him to collect £6 as compensation for an illness he had suffered. Dowling did not say what he was going to do with the money and soon left. [10]

Leaving the bicycle at the Mordialloc station, Dowling then took the train to the city where he made his way up Elizabeth Street to the Small Arms Company. ‘I wish to purchase a rifle for fox shooting,’ said Dowling to the man at the counter, Francis Henry Perkins. Perkins handed him a .32 Remington single shot rifle and asked, ‘Will that rifle suit you?’ ‘Yes,’ Replied Dowling. ‘What is your age? Are you 18 years of age?’ asked Perkins to which Dowling replied ‘Yes.’ Dowling paid £3:5:0 for the rifle, fifty cartridges and a pocket knife. He made sure the cartridges were the right type. That’s how easy it was in those days to obtain a lethal weapon. [11]

Returning on the 12.05 train to Mordialloc, Dowling arrived back at 1:00 p.m. He rode along Governor Road and stopped to take a few shots of the rifle for practice. It was just after 2:00 p.m. by the time Dowling arrived home to find Duff ploughing in the field opposite the Rochford home. The two antagonists spoke briefly. The following events happened quickly. Dowling fired a couple of shots at some birds and then fired a shot towards Duff to attract his attention. When the two faced each other, Dowling quickly reloaded the rifle. Duff started to run while calling out for help as Dowling chased him for about five paces. Dowling then stopped, took aim with the rifle at his shoulder and shot Duff in the back. So quick was the incident barely a few seconds passed between the first and fatal shots.

Rough plan of scene of murder. Reproduced with permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Records Office, Victoria.

Ploughing in an adjoining field to the north-east of the Dowling home near the main drain was James Duff, who was about 300 yards away from the incident. He heard his father’s cry after the second shot and James saw him running towards the Dowling home. Ernie then got on his bicycle and with rifle in hand rode easterly along Edithvale (Springvale) Road towards Dandenong. In the vicinity others heard the shots. Kinniburgh was working on the back verandah of the Dowling home making rugs and later ran 400 yards and jumped over four fences to reach Duff. George Peter Smyth, 14, witnessed the incident from about 300 yards away while digging potatoes in a field adjoining the Rochford home near the bridge over the main drain. When James Duff caught up, his father fell into his arms.

‘I am shot,’ he said to his only son.

‘Who shot you?’

‘Ernie Dowling with a rifle,’ replied Pat Duff who by now was fighting for his life.

‘What for?’ asked James, a question for which Pat Duff gave no answer.

‘I am done. I am shot through the lungs.’ He uttered a prayer and died.

It was 11.30 a.m. on 3 June when a travel stained and weary looking Ernie Dowling knocked on the door of the Ferntree Gully police station. After riding to Dandenong, Dowling left the bicycle there and walked to Belgrave via the main Gippsland Road. He spent the night sleeping rough and in the morning helped himself to some breakfast at a farm. On duty at the police station that morning was Mounted Constable Maurice James William Saker.

‘I am Dowling,’ he said to Saker at the same time producing a copy of The Age newspaper which referred to the shooting. Saker called Constable Thomas and on entering the office, Dowling repeated, ‘I am Dowling. I shot Pat Duff and it was an accident.’

‘Why did you run away?’ Thomas asked.

‘I got a fright,’ was all that Dowling said.

‘Do you wish to make a statement?’

‘Yes,’ replied Dowling.

‘You can make it of your own free will and accord,’ said Constable Thomas.

Dowling made a signed statement in which he affirmed the shooting was an accident and was detained awaiting the arrival of Detectives Piggott and Ashton.

For his statement he said, ‘I showed Duff the rifle and then had a shot at a sparrow which was about 10 feet distant. I killed the bird and left it lying where I shot it. Duff who was ploughing then went around with his team (of horses), the land was about eight chains in length when he came around again with his team he asked me for a loan of the rifle to have a shot at a mud lark. I lent it to him and he had a shot at the lark, he missed it and handed the gun back to me and went on with his team. I then had another shot at a bird and missed it, the shot disturbed five or six other mud larks further down the fence, they flew straight in front of me fairly low. I reloaded the rifle as fast as I could and fired at them. I saw Pat Duff fall, the birds were between him and me. I did not notice him when I fired the shot.’ [12]

While Dowling surrendered, Detectives Piggott and Ashton were at the scene of the shooting where they made a sketch and took three photographs. Piggott noted the point where Duff’s plough had stopped was 27 paces from the Edithvale (Springvale) Road fence while Duff had managed to run 215 paces towards the Dowling home before collapsing within nine feet of the paddock fence. Afterwards, on receiving word that Dowling had surrendered at Ferntree Gully, the detectives made haste to the town at the base of the Dandenong Ranges.

Under heavy questioning of Piggott and Ashton, Ernie Dowling made changes to his earlier statement.

‘Well Dowling, how do you feel today?’ asked Piggott at the Ferntree Gully station.

‘Pretty well under the circumstances thank you,’ replied Dowling.

‘I suppose you know Duff is dead?’

‘Yes,’ answered Dowling.

‘How did it occur?’

‘It was an accident. I was shooting birds,’ maintained Dowling. Dowling’s earlier statement was read in his presence in which he said it was about 1:30 p.m. when he went to Duff, a time that was obviously wrong considering Dowling had earlier travelled to the city.

‘I can’t understand why you were loitering so long at that bridge on the Edithvale Road. Why did you do that?’ asked Piggott.

‘I don’t know.’

‘Do you know that Duff was shot in the chest?’ continued Piggott.

‘Was he, I thought that he was shot in the back,’ answered Dowling. ‘Was there two shots in him?’

‘I don’t know. I haven’t seen the body,’ replied Piggott contradicting his earlier question of Duff being shot in the chest which would later be confirmed in the autopsy. ‘I don’t understand why Duff would be shot in the back if you were firing at a bird,’ continued Piggott. ‘Are you used to using a rifle amongst the horses?’

‘No.’

‘Do you mean to say that Duff would leave his horses in the plough to shoot birds, why they (the horses) would clear out with the plough?’ asked Piggott. ‘Is it not true that you have some grudge against Duff for his behaviour towards your mother?’

‘Yes, that is true and I will tell you the truth about it. I shot Duff and I bought a rifle to shoot him. I went to town and bought a revolver and some cartridges but I found they jammed so I decided to buy a rifle,’ explained Dowling.

‘You have told the police that you broke the rifle and threw it away. That is all nonsense. I must find the rifle. Where is it?’ continued Piggott.

‘Yes, I planted it in the ranges on the other side of Belgrave,’ Dowling admitted.

Dowling was taken to the spot about a mile and a half from Belgrave where the loaded rifle and revolver were found tied together with a white handkerchief amongst the ferns some 150 yards from the road. Dowling had loaded the weapons to keep the damp out. There were forty nine .44 calibre cartridges and a further thirty seven .32 cartridges for the rifle. That meant as many as thirteen had been used.

‘I am very sorry for you but there is a warrant here which must be executed.’

Detective Ashton then handed Mounted Constable Saker the warrant which was duly executed. Dowling was formally arrested and taken to the Melbourne Gaol. [13]

The post mortem examination of Patrick Joseph Duff was performed by Dr Crawford Henry Mollison the day of Duff’s death. His examination revealed that the bullet had entered Duff’s back between the tenth and eleventh ribs and then struck the side of Duff’s spine before passing through the lower and upper lobes of the right lung in an upward and outward direction leaving the chest between the fourth and fifth ribs, slightly above Duff’s nipple. Mollison confirmed death was due to a bullet wound of the chest.

The machinations of the law moved swiftly and the coronial inquest before Robert Hodgson Cole took place on 22 June, just nineteen days after Duff’s death. Both statements made by Ernie Dowling were read to the court. In his second statement Ernie explained: ‘I have been greatly worried in mind by this man Duff annoying my mother. I must have been mad at the time when I shot him. I told my mother on 3 December that if Duff did not keep away I would go a long way to stop him. I took this step because my mother would be left with two or three of my family who were unsuspecting while we would be out of the district with the chaff cutter and Duff would be at our house and have the run of it while we were away. These thoughts used to drive me nearly crazy.’ [14]

Cole was to find that Duff was ‘wilfully, feloniously and maliciously shot in the body and killed by Arthur Ernest Dowling’ and found him guilty of wilful murder. He was remanded in custody to stand trial in the Supreme Court. The trial took place on 18 July before Justice Mann and a jury. The same evidence as heard at the inquest was presented. Hugh Campbell Gemmell McIndoe (1883-1947) prosecuted for the Crown as Senior Crown Prosecutor (1919-1926), the equivalent of the Director of Public Prosecutions. For the defence, the Dowling’s retained two of the most formidable criminal defence barristers of the era in George Arnot Maxwell (1859-1935), described by Sir Robert Menzies as ‘the greatest criminal advocate I ever heard’ and William Ah Ket (1876-1936) who made up for Maxwell’s deficiencies as a cross examiner.

A visibly pale and distraught Grace Dowling told the Court that her son’s character had been very good up to the December incident and had shown much affection for her

‘Is the statement made by the accused as to your having been in the kitchen with the deceased correct?’ asked McIndoe.

‘Yes; but the occurrence has been explained to my husband to his satisfaction.’

‘Was that incident of such a character as to lead your son to suppose that Duff had misconducted himself with you?’ continued McIndoe.

‘Yes, as a matter of fact, such an attempt really was made by Duff.’

In the dock, Ernie Dowling sat for the greater part of the trial with his head bowed so low that only a crop of thick black hair was visible. But the hard part came when Dowling rose to address the Court. With long pauses and great difficulty, he said:

‘I was crazy; but I had no intention of shooting the man. That is all I have to say.’ His reply was an indication of the stress and the acceptance of what was to come.

In summing up the case for the jury, Justice Mann said, ‘…the jury must be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Dowling not only killed Duff, but that he shot at him. If you come to the conclusion that he intended to kill Duff, then the lad was guilty of murder. But if the jury thought that he killed Duff when firing at him – but not intending to kill – then he was guilty of manslaughter only. In cases of this kind, one naturally looked for some motive, and the story about his mother’s supposed dishonour supplied some explanation of why Dowling had acted as he did. But it was not the duty of the jury to go out of its way to find excuses for what had happened. The circumstances which had been related in explanation of the lad’s conduct might well weigh with those whose duty it was to estimate the moral quality attaching to the crime, and the punishment to be meted out in regard to it. The function of the jury was in another direction – to find whether or not this young man had committed the crime of murder. That he had suffered under a sense of great wrong was conceivable. He might have said that he would be his mother’s avenger; that he would punish the man whom he believed had wronged her with death. But such a punishment as that would be without trial and without warrant. It would, however, be a terrible state of things if a jury, by its verdict, should seem to sanction such a condition of affairs as that, and therefore they should be on their guard in this matter. At the same time, if the jury thought that the circumstances did not support the higher charge of murder, it would be competent for them to return a verdict of manslaughter.’ [15]

The jury retired and after two hours returned with the verdict of manslaughter. As Justice Mann summed up at Dowling’s sentencing, the jury believed that at the last moment, Dowling did not intend to kill Duff. He was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment with hard labour and at the completion, for detention in a reformatory.

Little is known what happened to Ernie Dowling after his prison term. He eventually settled in Victoria Point, Queensland and enlisted for active overseas service in World War II with the 1st Anti-Artillery Regiment (September 1942 – December 1943) [16] His marriage to Alma Dowling around 1930 produced four children who all died young; George Ernest (1931-40), Norman Leslie (1934-35), Leonard William (1938-68) and Ann (1948-50). He died on 12 September 1973 at Victoria Point aged 69. [17]

As for Patrick Joseph Duff, his remains were buried in the Cheltenham Pioneer Cemetery (RC ‘27’ 16) and lies in an unadorned grave together with his wife Essie.

Inspecting the scene of the murder. Reproduced with permission of the Keeper of Public Records, Public Records Office, Victoria.

Footnotes

- Index to Unassisted Inward Passenger Lists to Victoria (1852-1923): Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 7666 Fiche 533.

- Index to Unassisted Inward Passenger Lists to Victoria (1852-1923) Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 7666 Fiche 148.

- Between 1915 and 1921, those who are not listed for the entire period are: Frederick Alvin (1920-21) Frank Andrews (1915-16), Walter Andrews (1915-18), Robert Carr (1915-17), John Chapman (1919-1921), Charles Cummings (1915-17), Arthur Dowling (1918-21), R Horsley (1915-16), Sidney Knight (1919), William Lyndon (1915-16), John McDonald (1917), J Mazey (1915), R Parson (1921), William Pentland (1917), Michael Ryan (1915), Percy Skelton (1917-21), Charles Smith (1919), James Wade (1919), F A Walker (1918-20), F G Wall (1920-21), J Watson (1921). Only John Carroll, John and Mrs E Anderson and E Phillips and H E Phillips are listed for the entire period.

- Sands & McDougall Directory for 1903 & 1905; Electoral roll for the Division of Dandenong in 1909.

- Electoral Roll for the Division of Dandenong in 1914.

- This is also confirmed by the Electoral Roll for the Division of Flinders in 1919 which lists Esther and Patrick Duff of Wells Road, Chelsea.

- The Truth, 23 July 1921, page 3.

- Evidence of Arthur Ernest Dowling, Inquest of Patrick Joseph Duff 22 June 1921; Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 30/p/000 Unit 001932371.

- Evidence of Joseph Kinniburgh, Inquest of Patrick Joseph Duff 22 June 1921, Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 30/p/000 Unit 001932371.

- Evidence of Reginald Richard Nicholson, Inquest of Patrick Joseph Duff 22 June 1921, Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 30/p/000 Unit 001932371.

- Evidence of Francis Henry Perkins, Inquest of Patrick Joseph Duff 22 June 1921, Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 30/p/000 Unit 001932371.…..

- Evidence of Arthur Ernest Dowling, Inquest of Patrick Joseph Duff 22 June 1921, Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 30/p/000 Unit 001932371.…..

- Evidence of Frederick John Piggott, Inquest of Patrick Joseph Duff 22 June 1921, Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 30/p/000 Unit 001932371.….

- Evidence of Arthur Ernest Dowling, Inquest of Patrick Joseph Duff 22 June 1921, Public Records Office of Victoria VPRS 30/p/000 Unit 001932371.…..

- The Truth 23 July 1921 page 3.

- WW2 Nominal Roll for Arthur Ernest Dowling – http://ww2roll.gov.au/script/veteran.asp

- Dowling Family tree, Grawrock-Parker Genealogy – http://dwgslpfamily.com/genpages/p122.htm