Richard Edmund Courtney and ANZAC

Anzac Cove, 2008. Courtesy Pam Whitehead.

The Courtney family has a strong connection with Cheltenham. Thomas Wilson Courtney and his wife Mary Jane (Fleming) were residents in Cheltenham in the 1850s. Thomas was the first school master of the Church of England school in Silver Street [1] Thomas and Mary had twelve children, two of whom were born in Cheltenham, Thomas John and Jane. [2] Later as a civil servant, Thomas Wilson Courtney was stationed at Castlemaine but he died in 1906 at Coburg.

The eleventh child, William Wilson Courtney, a pharmacist, conducted the dispensary in Charman Road, Cheltenham, opposite the State School. Three of his brothers held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel during World War One, and one, Richard Edmund, commanded the 14th Battalion during part of the Dardanelles campaign. The position of the battalion was described as a precarious but critical one along the lip of Monash Valley in the heights above ANZAC Cove. [3] There were three posts, Courtney’s, Quinn’s and Steele’s. Courtney’s post named after Richard Edmund, was the scene of particularly ferocious fighting during the Turkish attack of 19 May 1915. The following letter was written by Richard Edmund Courtney while a patient in hospital in Malta to his elder brother Thomas John , also a colonel in the Australian army. Thomas at 58 years of age was in command of troop ships transporting Australian soldiers to the fighting front. [4] The letter describes graphically the grim realities of the battles on Gallipoli peninsula during the early stages of the Allied invasion in 1915. [5]

Landing at Anzac Cove, 1915.

Blue Sisters’ Hospital

St Julian’s

Malta

15/6/15

My dear Tom,

I fancy some of the details from a C.O’s point of view may interest some of you. I preface it with the reminder that the writer is now a sick man, weary and weak A tale of a fight should be written just after it – in the proper atmosphere, but one has other things on hand then and one sees the worst side of the war – the dead and wounded pals. But for the fight. Picture a huge boomerang of defending Australians and two ‘Posts’ right at the bend of it. There was “Quinn’s Post” on the left and “Courtney’s Post” on the right – really one big Post connected by a trench, the limit of each command being marked by our blue and gold flag, so an attack on Quinn’s – and it came every night or morning – is an attack on us all. The nearest Turkish trenches in front of Courtney’s were 25 yards away, in part of Quinn’s only 5 yards. We threw bombs at each other.

Two companies of ours are in the trenches, 175 yards in length, or in the communication trenches and supports. Major Rankine, D.S.O. – none ever earned it more honourably – is in charge of the trenches. 60 or 70 yards down the hill – or rather the precipice (it is 1 in 2’) are two more companies under the C.O. in reserve, sitting, or rather at first sleeping in their dugouts and quite ready to hear “Stand to Arms” at any moment. Yes, for the Turks have been shelling the trenches for an hour or more, the unfailing warning of an attack bigger than usual. They smash our parapet and cause much overtime, for we must repair the parapet before their attack comes. They kill none and wound very few. In my comfortable dugout lay three very weary anxious officers, so tired, so dirty, yet so determined, and above all so confident in the strength of our defence and the perfection of our communications (the great factor in my own scheme of command). Each company has a signal orderly beside the Signallers’ dug-out, just above ours. Right at my feet sits the orderly on duty (only 1 ½ hour tour for its very, very important). 50 or 60 yards below is the Brigade Head Quarters and two more of our orderlies there. Battalion Head Quarters and Pioneers are ten yards below me, and thanks to the eight months’ training we have a solid disciplined fighting machine: and I have said the staff is calmly confident in spite of the G.O.C’s message that “Two more divisions of Turks have reinforced them and are massing on our front.”

Let me gather up the sequence of events, and if this is personal a bit my excuse is that it was written for those of you whose interests are personal rather than general

8.15 p.m. We retire to bed(?) fully clothed as usual – Charley, calm, methodical and, at times, jocular as ever. “Baby” (which is the regimental nickname for one of the reliable and brave ‘boys’), my Signalling Officer, Les, Ball, and myself, we yarn of home, draw mental pictures of our return, interspersed with questions and answers much more pertinent to the job on hand. Every now and then I sit up and light the candle as we hear the Head Quarters’ Orderly come with a message. I receipt it, read it, give it to Charley, and we both say awful swear words for our rest is disturbed by some detail that can easily wait till daylight, so we quietly shut up; and close our eyes and flatter ourselves that we are asleep. But every half hour or less comes an orderly, and so it goes on, the musketry never ceasing for a moment all the time, but one does doze a little now and again, never a solid sleep, we haven’t had such for a month nearly. Do you wonder we are fagged out?

About 3 a.m. a sudden burst of heavy rifle fire, quite a common occurrence, not causing more than an awakening, and a wait for a minute or two till the firing line sends its report. The message says whether the attack is on us or elsewhere, for in the valley the echoes make it impossible to say where the firing really is heaviest. But this morning it is “Major Rankine’s compliments, sir, the enemy is attacking us and Quinn’s.” Orderly: Send ‘A’ and ‘D’ Orderlies, order Companies to stand to arms.” Mr Nall reports to Brigade Head Quarters. In less than two minutes the whole Battalion is awake, equipped and quietly sitting in their dugouts. Not any roaring, no rushing about, no shouting (in fact five minutes later someone wants to know why we are not standing to arms.) Some people like a noise!

Charley and I just sit up and wait, calmly getting the necessary flow of messages from the firing line and hearing the ‘high’ shots passing over our heads, the whistling bullets that may be 50 feet over us, or, as too often, land just in our dugouts, ricochets off the top of the hill. So the infernal roar goes on. Mr Groom comes running quietly down, his head tied up. “Things are pretty thick, sir, Major Rankine would like two Platoons” – ‘A’ Company Orderly send to O.C. ‘A’ Company”, etc, etc.

“Where did they get you Teddy?”

“In the cheek, it’s only slight” and back goes a hero, back to the trench and fights for three hours more, for he knows how shorthanded we are (all our Captains gone) till his nerves can stand it no longer and faintness makes him go down.

“They got Mr Rutland, sir.” (an Orderly speaks).

“Bad?”

“Yes, sir, killed. He was working his gun playing Hell with them and they got him right through the heart.”

“Is the machine gun Sergeant there?”

“Yes, sir, he’s all right.

(To Charley) – “Send the Regimental Sergeant Major up to keep his eye on the guns.” (Exit Charles)

A weary subaltern – weary, but working in the same trenches without a break sent down by Bobby – just to steady his nerves – with a faked message. I get the strength of things, give him some tea which my faithful Batman has made. We yearn quietly and he adds to the really awful mental strain I confess to by telling me how poor old Jack Rutland was killed.

“They’ve got Mr Curwen-Walker, sir.”

“Badly?”

“I’m afraid so, sir, the doctor has fixed him up, he’s doing down now.”

It’s broad daylight now, 5 o’clock or later, and one can see the bearers passing, or rather climbing or sliding down the hill to the valley. Such a lot of them.

“Major Rankine’s compliments, sir, can you send up a Company, we are getting it very hot?”

‘D’ Company Orderly go to O.C. ‘D’ Company and tell him, etc., etc.

I have told in a few minutes what took two hours or more to eventuate and a constant stream of Orderlies kept the thing going on quietly (how the men chaff about me and this good word ‘quietly’;) Charley and I and Baby, when he comes up for a change from Brigade headquarters, just smoke a fag or calm some excited orderly or too energetic subaltern – and we wait. Oh, God only knows what strain we bear. The responsibility, the anxiety lest our line be broken, the constant testing of our readiness to meet such an emergency, the terrible effort to lie to one’s pals and oneself by keeping calm and unmoved, to steady ones fingers when lighting the comforting and deceiving fag. A bounding, jumping, excited youth almost knocks us over as he rushes at us all smiles – “I’ve got one, sir the …… got me at last.” (The point is that he never swears usually).

“Well, Harry, old chap, is it bad?”

“Not a bit, only in the shoulder, I’m going up in a minute. Major Rankine sent me down to have a spell ….. I’m off to get even with the brutes.”

His left arm is tied up and he is badly hit, too excited to know it, and I keep him by asking for details of the fight. Then he calms down and drinks tea and ‘thinks he’ll have a rest’. Finally he goes up to the firing line and gets his kit and he too goes ‘down to the beach’:

“Goodbye Colonel, I’ll be back in a few days.”

“He isn’t so bad as we thought and will get over it.”

This is Harry Boyle, a Duntroon youth of whom I could never write enough. The youngest officer who left Australia (now a Captain), struck more fight than any other officer up to the day he was hit, and behaved like a veteran. Had command of his company, too, for some time with only two other boys to help him. Too young at 19? Not by a long chalk.

“Gunner’s done, sir.” (Reg. Cox)

“What, killed?”

“No, but broken down – concussion. He just collapsed, and the doctor says he’ll never fight again.” (He is in Malta, St Andrew’s, mending slowly).

My mind rushes through the list of officers who are left, about 12 now out of 33. Then the awful tugging one feels going on in one’s brain and all the time the damned infernal din as the Turks hammer away.

A stroll or two along the terrace just to see that things are O.K. below and I meet another weary subaltern, there are few left now – “Poor old Bill, sir.” He can hardly tell me, for Bill Hamilton was everybody’s favourite. “Don’t know how it happened. We found him in a trench shot through the mouth, three chambers of his revolver empty. Don’t know, sir, don’t know, we found him in the trench shot through the mouth.” I won’t continue this, I dimly remember the awful strain, yes, I remember wondering how long I could keep this up, keeping cool and keeping one’s hand on things and just working the right levers at the right time. One never can know it, never anticipate it or prepare for it, it’s too hard, but one must do it if he is to command. It’s far easier to rush about up in the trenches or in the firing line, giving vent to one’s feelings or letting off steam, or keeping oneself occupied with the rush of a close event, but I’m satisfied it’s not the game for a Commanding Officer.

We try to sleep that day but it’s a poorer effort then usual. Bobby (Rankine) comes down and we talk things over and all the ‘boys’ come along and we hear of incidents of gallantry – how ten Turks actually took a party trench by rushing with bombs and knocked our men out – how poor old Bill Hamilton went to see and …. No one knows, how Keith Crabbe organised a ruse against these brutes while a corporal (Jacka, since awarded V.C.) went single handed to the opposite end and of the seven left he killed five and helped two out of the trench with his bayonet. Total killed by the corporal, seven. Have reported him and hope he gets his reward.

Memorial and Graves of Australian and New Zealand Troops at Gallipoli, 2008. Courtesy Pam Whitehead.

So the quiet day goes on, never much chance for sleep – too tired to sleep anyhow.

We get things in order, relieve the firing line and send the same old subalterns back to the trenches. We have no others to take their places.

About 4 o’clock, while at afternoon tea, I saw General Godley passing along the terrace towards me all smiles and his had stretched out as I went to meet him, and he was so kindly complimentary in his sincere remarks. I merely thanked him and told him ‘we had quietly done our job and would quietly go on doing it.’ Then he told me very nicely what a great fight we had put up, and, what we never knew before, that two divisions had attacked the line, the main attack being against Quinn’s and Courtney’s posts, and he told us of the awful slaughter we had made. Then he spoke kindly again and was more complimentary and I could merely gulp out “thank you” and my heart filled and the tears poured down my cheeks. I was broken by kind words when all the Turks on the Peninsula couldn’t move me, nor all the horrors of war. Such is human frailty. Such is a big fight from the warped memory of a sick C.O.

This fight I have described is only one of many, the biggest certainly, but we had the same thing every night almost for three weeks, once they kept us going for nine hours, but not so hot.

Looking back – Broadmeadows on October 1st – a mob. The work, the worry, then the sea trip and its new problems, all handled by the ship’s staff in such a way as to command success, but, of the worry. Egypt – new ways of worrying a C.O. and his imperturbable staff. Work, work, always but so cheerfully, because from October 1st everyone had tried so hard to do his bit. Then the final move to Gallipoli and another anxious wait for two or three weeks on the boat. “Will the men stick it?” “Have our methods been right after all?” “What will the verdict be?” Calm and confident through it all and never a hint to a soul that I was even troubled with such a thought, but I was much troubled too – I blamed my liver and my neuralgia. Then look at our landing. All that Sunday night we lay off Anzac Cove and the wounded were being brought to our ship, already crowded with the Battalion and over 700 wounded were taken aboard.

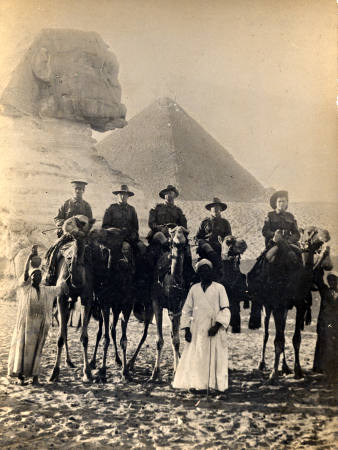

Australian soldiers in Egypt, c1916. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society.

This was our first introduction to real war. There were my pals. Poor old Frank Le Maistre tied up and almost bereft of his senses – never will I forget it all, much less the Monday which followed. We found two destroyers alongside after breakfast and into these we crowded and started for the beach about a mile away. Some silly shrapnel got about us but didn’t touch our boat, had a rotten feeling all the time though. About 600 yards from land we clambered across into lighters and our first casualty occurred, not in my boat, a man was killed by shrapnel which was now welcoming us too closely and we kept ‘ducking’. Out of the lighters and we hope to get right at it and relieve our feelings – but no – we simply assemble and get as many as possible separated from the crowd of all sorts on the beach and then we huddle up against the hill and try to make shelter. Room for about 100 all told out of nearly 800; the rest were exposed and it is one of the mysteries of that day that not a shell landed on the mass of men, where later on hardly a man was safe; but the beastly shrapnel kept bursting over us and landing in the sea not far away, and there we lay all day and all that weary night being ‘blooded’’ to fight in this nerve-racking way and never a chance to fire a shot or relieve our feelings.

Yes, and look at the awful Tuesday. At 10.30 a.m. we move up the valley, a rough track then, can go only in single file, shelled all the way – a few men hit. We reach the top finally in pieces and then began our real meeting of lead and here the story is too complicated to put on paper easily. Sufficient to say I found myself in command of Quinn’s and Courtney’s Posts, as they are now named – the two hottest places in the line, and so my command lasted for four days till I was relieved at Quinn’s. The first day I lost Jack Adams, my second in command, and Captain Hoggarth. Two other Captains had gone sick before we landed. In three days I had lost five Captains, four Subalterns, and myself fell a victim to the flu. It was awfully cold at nights and at times it rained, but harder than all the Turks kept up an incessant attack on these two posts and our losses were naturally heavy. The number I omit at present. But I couldn’t go ‘sick’ not much; the really superhuman bravery and calmness of the officers and men in the three days of awe, of death, and of hardships which never ceased for a moment are quite beyond my expression – beyond what any man could ever expect and far beyond all praise. Only the absolute confidence in the battalion – a confidence begotten by watching the training of all ranks closely for seven months and intimate knowledge of all ranks kept me ‘clothed and in my right mind’. Really I never feared a break, close as we must have been to it at times. Now in calm retreat I almost give way to emotion as I look back on the men who did that job. Yes, and those who gave their lives in doing it.

I didn’t mean to worry you Tom with all this detail, buts I have just wandered on and one and it relieves my feelings, so you must forgive my prolixity, but don’t think I have told you all or half, I have omitted much and a good deal purposely It can keep and will fill in the remaining causes of my banal break-up possibly.

Well, after a few days I get rid of Quinn’s Post and we consolidated Courtney’s Post, and for a fortnight we were at it nightly almost without exception – the same story as I began with but not always so hot.

Let me close with this outline. I can give anyone details by yarning if ever anyone want to hear about what Ian Hamilton described as “The bloodiest fighting I’ve ever known.”

Memorial at Anzac Cove commemorating the loss of thousands of Turkish and Anzac soldiers contains the words of Mustafa Kemal Attaturk, a leader of Turkish troops at Gallipoli and first president of Turkey. Courtesy Pam Whitehead.

Richard Edmond Courtney had graduated with a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor of Laws from Melbourne University and in civilian life was a solicitor. On the 8th of September 1914 when 44 years of age he applied for a commission in the Australian Military Forces and was appointed as the commanding officer of the 14th Battalion. His military service commenced as a bugler in the Castlemaine Victorian Rifles and concluded in April 1916 after 32 years of service. Two years earlier he landed with Australian and New Zealand troops at ANZAC Cove and after a short time of ferocious fighting was conveyed to the hospital of the Blue Sisters at St Julian’s, Malta. It was from there that he wrote the above letter to his elder brother. On 28 June 1916 he was admitted to Lady Meynell’s Hospital in London with heart strain. After eleven days he was discharged and appeared before a medical board where he was classified as unfit for general service but could undertake light duties at home; no route marching or severe exertion they advised. He left England on 17 March 1916. Seven months later he was acting Commandant of the 5th Military District in Perth and three years on he was dead. [6]

Lt Colonel Richard Edmond Courtney was mentioned in dispatches on several occasions and on 6 February 1916 the London Gazette announced that the King had made him a Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath for distinguished service in the field during operations at the Dardenelles

View of Gallipoli from the Australian and New Zealand Memorial, 2008. Courtesy Pam Whitehead.

Footnotes

- This school was subsequently closed but some decades later the Education Department built Cheltenham East Primary School on the site.

- Victorian Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages.

- http://www.awm.gov.au/units/place_66.asp

- Letter courtesy of Richard Mickelburough.

- The letter here is an abridged version of the original letter.

- National Archives of Australia: Personnel Records of Richard Edmond Courtney.