Alexander Vause Macdonald: Mordialloc Pioneer

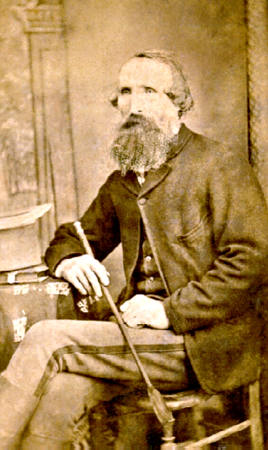

Alexander Vause Macdonald. Courtesy Peter Dack.

Alexander Vause Macdonald’s hat was found floating in the Mordialloc Creek on the morning of 20 December 1881. He had last been seen crossing the bridge the previous evening at ten o’clock. [3] That day had seen the official opening of the Melbourne to Mordialloc railway line with a luncheon at the Bridge Hotel under the management of Richard Goff Bloxsidge. [4] Some people at the function were invited by Mrs Bloxsidge to continue the celebrations into the evening. Alexander Macdonald, being a respected member of the Mordialloc community, was probably amongst that number. It was feared that Macdonald had fallen into the creek and drowned. (A more colourful family story was that a drunk Alexander attempted to jump his horse across the creek, fell in and drowned.) [5] A few days later Mounted Constable Strachan assisted by local residents dragged the creek in an attempt to find the body but they were not successful. The Brighton Southern Cross reported on 24 December 1881 that the body was later found only a few yards from the hotel. A magisterial enquiry conducted by Thomas Attenborough, a Dingley pioneer, concluded that Alexander Macdonald’s death was an accidental drowning. [6] Macdonald was 65 years of age and was buried in the Cheltenham Pioneer Cemetery on 24 December 1881 with the committal being conducted by Robert Rigg, the head teacher of the Mordialloc School and a Wesleyan preacher. [7][8]

Born in 1817 to Murdo Macdonald and Flora Morrision at Bracadale near Sleat on the Isle of Skye in Scotland, Alexander Macdonald sailed on the Earl Durham to Sydney where he arrived on 2 January 1839. [9]. He was 21 years of age. After only a few months in the new country he set out overland for Melbourne where he joined his brother on a sheep run. [10] He also became involved with his brother in conducting the Travellers’ Rest a stopping place for travellers at the Mordialloc Creek [11].

Alexander Macdonald married Isabella Munro at Scots Church, Melbourne on 17 February 1841 [12] He was aged 24 and Isabella was 21. The officiating minister was James Forbes and the witnesses were John McGregor and Rachel McDonald who was a younger sister of Alexander. After his marriage he started the sheep run named Stringy Bark, on the Yarra, near where Kew is today. [13] [14]. It was from there that the family walked to church because ‘They would not put a horse to harness on the Sabbath. Likewise all meals had to be prepared the previous day. There was definitely no work of any kind done on the Sabbath’ according to Ethel Dack. [15]

Isabella, Alexander’s wife, born on the Isle of Skye, had travelled with her mother on the Glen Huntley arriving in the Port Phillip District 17 April 1840. Shipping records described Isabella as a single woman of twenty years, a housemaid who was not engaged for employment. [16] Her mother was travelling under her maiden name, Mary McKenzie, a dairymaid, and gave her age as 38 when in fact she was eight years older. This falsification of her age was necessary to make her eligible for the ‘free’ government emigration scheme which was restricted to persons under 40 years of age.

The Glen Huntley seemed to have been an ill-fated ship. At the beginning of its journey from Scotland in December 1839 several disasters struck. The ship ran on to rocks damaging its hull and later it collided with another vessel. After some delay it arrived at Port Phillip District on 17 April 1840 flying the Yellow Quarantine flag indicating it was carrying passengers with infectious diseases. Of a passenger complement of 170 passengers, during the voyage 105 contacted various diseases including fever, scarlatina, measles, small pox, and chicken pox. The ship was quarantined and accommodation was prepared for those affected in a rough canvas town on the coastal cliffs at St Kilda known as Little Red Bluff. Both Mary and Isabella were held for a period in the camp at Little Red Bluff or Red Cliffs, known today as Point Ormond. [17]

Painting by Petrie of Macdonald’s homestead at Mordialloc. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

It was in 1842 that the first child of Alexander and Isabella, was born according to his birth certificate, at Plenty Run. In 1844 the family moved to Mordialloc. There, as a squatter, he took over a larger run than the Stringy Bark on the Yarra River. The new squat, stretched from the vicinity of the Mordialloc Creek, north along the foreshore and into the interior. Later, when land was offered for purchase by the government, Alexander Macdonald exercised his ‘pre-emptive right’ to purchase fifty acres. For this he paid seventy five pounds on 25 June 1855. [18] The pre-emptive right system allowed squatters to buy up to 640 acres of their runs before the land was made available for purchase by selectors. A month after the purchase he mortgaged this land for seven hundred pounds with A B Balcombe and on 29 February 1860 he sold the land to Adolphus Fraser. [19] It was on a small portion of this land, on the crest of the hill, he built a hotel that became known as the Mordialloc. Macdonald conducted this hotel from 1853 until April 1859. [20] [21] Over time this small simple wooden structure became much larger and more complex with additions and reconstructions. More than a hundred and fifty years since Macdonald began his occupancy the enterprise was renamed the Kingston Sporting Club.

Mordialloc Hotel, c1918. Courtesy Kevin Wilson.

From 1842 to 1852 Alexander Macdonald had a Run known as Mordiallock No2 which was to the East of the township. This run of five square miles was conducted in conjunction with Hunter from November 1848 to January 1850 and with Ballingall from 1850 to 1851. [22] There, after the creation of the colony of Victoria in 1851 when the government withdrew the leases held by squatters, surveyed the land, divided it into portions and offered it for sale by auction, Alexander Macdonald took the opportunity to purchase 453 acres of the original run. He did this on 24 September 1855. He paid the substantial sum of five hundred and sixty seven pounds six shillings and five pence for this land between Lower Dandenong Road and Governor Road adjoining land purchased by members of the Keys family. It was sold as lot 43. The purchase of this land occurred only three months after purchasing the 50 acre beachside property. To finance the new acquisition a substantial sum of money had to be found and Macdonald probably did this by mortgaging the 50 acres for £700 to A B Balcombe of the Briars, Mount Martha, who owned land that subsequently became the site of Mentone. [23]

District Pastoral Runs, c1860.

For a few years after 1855 Macdonald was purchasing hay and potatoes from James McKnight a pioneer of Cheltenham. In November 55 he purchased 1 ton 14 cwt of hay at £10 per ton , in December 56 the purchase was 3 ton 5 cwt at £9 per ton while in January 1857 he purchased £3 13 1 worth of hay. [24]. These were times when the natural fodder to feed his cattle on his own barely developed property would have been inadequate.

In the 1890s the Macdonald family, some years after Alexander’s death, sold this land to William Harkness McLorinan, a Mordialloc contractor for £100 but with McLorinan taking responsibility for the mortgage held by Balcombe. In 1906 the land was acquired by the Government under the Small Improved Holdings Act for seventeen pounds one shilling and six pence half penny per acre providing a very substantial profit to McLorinan. [25] The Government then subdivided the land into 38 allotments ranging in size from 10 to 12 acres. This was part of the Government’s plan to settle small farmers on land. [26]

For thirty seven years Alexander Vause Macdonald was a resident of Mordialloc. During that time, in addition to his work as a grazier and hotel keeper, he contributed to the community in various ways. In 1861 he made a deposition at the official inquiry into the death of a aboriginal woman known to the European settlers as Betsy. In that statement he pointed out that he distributed rations, flour, sugar, tea, tobacco, and soap together with an annual allocation of blankets, to the aboriginals at the request of Mr Thomas who held the official position of Protector of Aborigines. For this work he was not paid. He did it for the ‘sake of charity’. [27]

Alexander Macdonald was a signatory in 1865, along with several other Mordialloc residents, to a petition requesting a government grant to establish a primary school in their town. The petition noted that he had two children as potential students; twelve year old Alexander and six year old Caroline. They were the youngest two children of ten in Alexander and Isabella’s family. The other children were Malcolm James Munro (born1842), Flora (c1844), Charles (1846), Margaret Mary (1848), John (died as an infant), Jessie Ann (1849), Mary (died as an infant), Anna Isabella (1861). All the children except for Malcolm were born in Mordialloc. [28] In the Victorian Government Gazette of 1866 Alexander Macdonald was noted as a member of the school committee. [29] Earlier, in 1853, he was advertising in the Argus newspaper seeking the owners of two boats that had been washed up on the beach at Mordialloc. One was a large damaged ship’s boat painted a lead colour with the name Elizabeth Hughes lettered on the stern; the other boat was painted black with a red streak. Owners were advised to contact ‘A V Macdonald of Mordiallock (sic)’. [30]

The contribution of Alexander Vause Macdonald is acknowledged on a plaque in the Scullin Reserve at Mordialloc. The plaque reads:

This cairn was erected by the citizens of Mordialloc to commemorate the first permanent white settler in the district Alexander Macdonald whose homestead was built near this spot in 1845.

And also to commemorate the Boonurrong Aboriginal Tribe whose camping grounds were along the banks of the Mordialloc Creek.

24th May 1970

Cairn in Scullin Reserve Mordialloc, 2008. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

Footnotes

- Alexander’s surname is inconsistently spelt in official documents. Where he had signed his own name he spells it as Macdonald. This is the spelling used throughout this article in relation to him.

- Several sources indicate that Alexander Macdonald donated two acre allotments to both the Church of Scotland and the Church of England with the one acre between for the establishment of a Common School. Documents from Lands Victoria dispute this. These two churches and the education authorities gained their allotments through Crown Grants. See Government Gazette No

- Brighton Southern Cross 24 December 1881.

- See, Whitehead G. J., Richard Goff Bloxsidge: Publican, Councillor and Sportsman, Kingston Historical Website.

- Recounted by Peter Dack.

- Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages - Death Certificate.

- Cheltenham Pioneers’ Cemetery - Grave 44, Compartment A, Presbyterian Section.

- See, Whitehead G. J., Robert Edward Rigg, Headmaster, Preacher and Soldier, Kingston Historical Website.

- Dack, Graeme – Macdonald, McSween-McSwain, Genealogy c1790-1999. Information from the ‘Colonial Secretary’ Archives Office Mitchell Library, Sydney.

- McGuire, F in Mordialloc- the early days, suggests that this was the Point Nepean Run 1839-1841 at Mordialloc.

- McCrae H. (Ed), Georgiana’s Journal, Melbourne 1841-1844 page 124.

- Marriage Certificate – Registrar General’s Office, Sydney. The entry does not include the name of the church and Graeme Dack believes the church was the Scottish Gaelic Church in Carlton and not Scots Church in Melbourne.

- Sutherland, A., Victoria and its Metropolis, 1888.

- Rachel was born in 1819. Note spelling of her surname. Macdonald is spelt several different ways in official documents but where Alexander signed his name he used the Macdonald spelling.

- Stories told to Graeme Dack and recorded by her.

- Archies Roll No 2743 Glen Huntly p140.

- Dack, Graeme. ibid

- Land Victoria – Land Purchase, Document 33926 - Allotment 22 Section 24.

- Land Victoria – Document 8676a – Rennison.

- Dack, Graeme. ibid

- Billis R & Kenyon A, Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip 1974.

- Billis R & Kenyon A, op.cit.

- Land Victoria – Document 8676a – Rennison.

- Diary of Mary McKnight- Showing family income and expenditure.

- Land Victoria – Document 8676a – Rennison.

- Hibbin, G., A History of the City of Springvale: Constellation of Communities, 1984 p108. Government Legislation.

- Joy, S., The Search for the Beaumaris Cemetery, Victoria, 1855-1865 Page 78. and Public Records Office VPRS 24, Unit 101, File No 788.

- Dack, Graeme. ibid.

- Victorian Government Gazette: 31 August 1866.

- The Argus, 30 August, 1853.