Cheltenham Railway Station

Station sign recording the historic nature of the buildings 2006. Photographer Joe Astbury. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

The late 1870s saw the beginning of a massive program to construct railway lines throughout Victoria. One of these lines was from Caulfield to Frankston. A survey undertaken by J P Madden, an engineer employed by the railways, established the route, although this was later modified on instructions from some higher authority. The revised line rather than following a direct line from Caulfield to Mordialloc curved westward, crossing the main road on several occasions. This revised route necessitated the construction of more than twenty crossings each associated with accommodation for gate keepers. [1]

Initially, the date of the official opening of the completed single track to Mordialloc was delayed, possibly because of some doubt about the quality of the ballast and some criticism of the sinuous route the line eventually took. The big day when politicians, local councillors and residents gathered at Mordialloc to celebrate the achievement was on 19 December 1881. [2]

At the time of the official opening of the line to Mordialloc no station buildings had been constructed despite the fact that tenders had been called in the Government Gazette of 26 May 1881 and subsequently in the Argus newspaper on 30 August 1881 for what became stations at Glenhuntly, Ormond, Bentleigh, Moorabbin, Highett, Cheltenham, Mentone and Mordialloc. [3] [4] This was due to the intervention of Thomas Bent as Minister of Railways, who was not satisfied with the designs based upon stations already constructed on the Shepparton Line. [5] It is suggested that Bent saw the stations as being too expensive. [6] However platforms and sidings were completed, ready to receive passengers. This situation was not welcomed by local residents who pressed for the provision of suitable accommodation and, in addition, improved approaches to the stations. A public meeting convened by G W Taylor at Cheltenham, held in the Mechanics’ Hall, in June 1882, proposed that a deputation wait upon the Minister of Railways to present their views about these matters as well as the need to increase the number of trains and to decrease the cost of fares.[7]

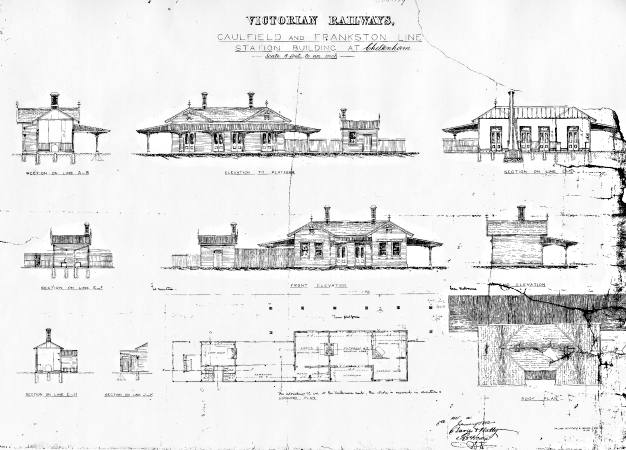

An October 1881 newspaper report suggested that station buildings were to be cheap, but substantial, costing about £370 each. [8] The revised plans demanded by Minister Bent and prepared by S E Bindley, an architect of the Education Department, were said to achieve financial savings. [9] The final design accepted for station buildings along the Caulfield –Mordialloc line was referred to as the ‘Garden Cottage Style’, described as a symmetrical building with two gables either side of a central entry covered by a wide veranda. The gables were surmounted with iron finials and two polychrome brick chimneys. On entry, to the right was the booking office and to the left a ladies’ waiting room from which toilets were accessed across a yard. The male toilets and urinals were accessed from the station platform. A wide veranda decorated with iron lacework and brackets fronted the building to the railway platform. [10]

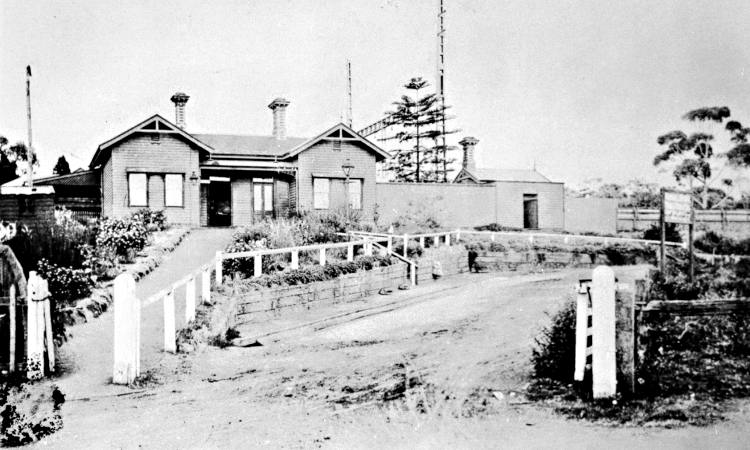

Cheltenham Railway Station c1920. Photographer Percy Fairlam. Courtesy Betty Kuc.

Ward & Donnelly in their survey of Victoria’s railway stations point out that five stations on the Frankston line were built in what they categorize as the Cheltenham Style; Cheltenham, Highett, Glenhuntly, Mordialloc and Frankston. [11] This design was only used for a period of two years. These stations were built in a rush, with four of the five contracts being signed on the same day, on 5 January 1882. The station built at Cheltenham by Davies and Batty varied from the description given above in that the plan was reversed so that on entry the booking office was to the left and the ladies waiting room to the right. [12] The lamp room and toilets were to the Melbourne end of the platform. As Ward & Donnelly point out, the lamp room was built at some distance from the main building as it constituted a danger, while the pan-serviced toilet facilities were separated ‘for good reason’. [13]

Architectural Drawings of Cheltenham Station 1881. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

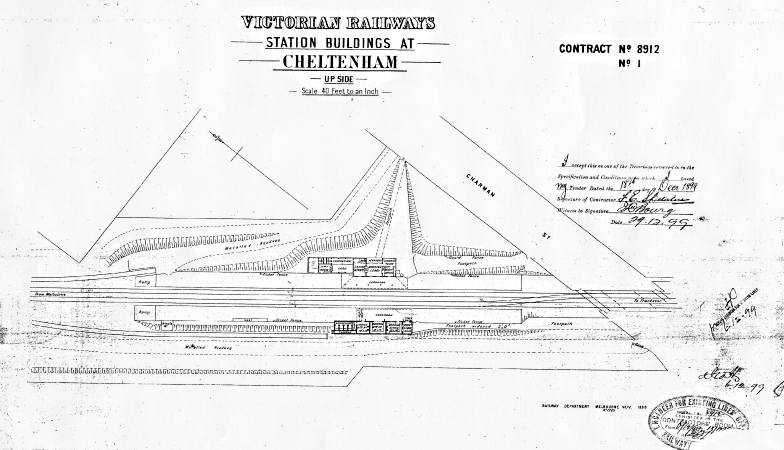

The June 1881 plan of the station grounds at Cheltenham shows a central access pathway from the station building to Charman Road together with a metalled road to the left leading to the carriage dock. There was one branch line or siding leading to the carriage dock, while another travelled to the rear of the up-line platform. In addition to the two platforms there were three railway houses which provided for the gate keepers on Tulip Road (Park Road) and Charman Road and the station master and his family on Tulip Road. Ward & Donnelly suggest the decision not to include a residence on the station, as was the case with some stations, was probably due ‘to the frequent passage of trains in the metropolitan area combined with the resultant heavier passenger traffic to suggest that a more distant place of abode for a station master and his family was preferable.’ [14]

Cheltenham Railway Station c1920. Photographer Percy Fairlam. Courtesy Betty Kuc.

The 1881 plan includes the up line platform on which were several small temporary buildings. These relatively simple shelters became the centre of community attention a few years later. In 1889 Cr Vail of the Shire of Moorabbin was urging his colleagues to censure the Railway Commissioners for not providing suitable accommodation at Cheltenham. He said he had witnessed several ladies among thirty people standing in the rain on the platform waiting the arrival of a train where the only shelter was a small box-like office to which passengers were refused admittance by a railway official. (It should be noted that with the exception of Cheltenham, all stations from Glenhuntly to Mordialloc had their major facilities built on the up-platform, whereas with Cheltenham they were constructed on the ‘down-side’ platform.) [15] It was some ten years later that the railway authorities took action with building activity being undertaken by F E Shillabeer after the contract was signed in December 1899. This building was a ‘one-off’ concerning its design. It included a booking lobby with ‘check gate’, booking office, general work area, a ladies’ waiting area and ladies’ closets with rear access for the cleaner or nightman. There were urinals provided for males further down at the Melbourne end of the platform. At the same time as these additions to the buildings were to be made there were modifications to the grounds of the down station. A new footpath was to be constructed to run parallel to the platform from the booking office to Charman Road at the rear of some shops.

Architectural Drawing for Cheltenham Station 1899. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

Writing in 1982 Ward & Donnelly suggested the Cheltenham style stations had suffered over the years with alterations and extensions at one or two ends. Successive bouts of maintenance had resulted in the removal of many decorative elements but their shells largely remained intact. [16] The Cheltenham ‘down’ station in 1982 retained the original yards and lamp room while the toilets remained close to their original condition. Given this situation Ward & Donnelly judged the Cheltenham building to be the most important of its group to survive. The up station at Cheltenham received extensive maintenance, modernisation and extension in 1992 making it an ‘island station building’.

Up Platform renovation at Cheltenham 1992. Courtesy Leader Collection.

Since 1982 further changes have been made to the down side Cheltenham station. Fireplaces have been removed, doors removed and only one polychrome brick chimney remains. The lamp room and toilets no longer exist and a ramp has been constructed on the platform to allow easier access by people with a physical disability. The two pathways from the station to Charman road have been covered with heavy and unattractive roofing to protect passengers from extremes of weather. While the platform has lost much of its original charm, and the smelly pan toilets, some of its original features can still be identified.

Down Platform of Cheltenham Station 1982. Courtesy Leader Collection.

Footnotes

- See, Whitehead, G., Establishing a Railway Line to Mordialloc, Kingston Historical Website.

- See, Whitehead, G., Opening of the Mordialloc Railway Station, Kingston Historical Website.

- The Argus, 20 December 1881.

- The names for some stations have varied. For example Mentone was Beaumaris and later Balcombe while Moorabbin was Brighton South. See article Kingston Historical Website Article 329.

- The Argus, 20 December 1881.

- Bryce Raworth, City of Kingston Heritage Study.

- The Argus, 28 June 1882.

- The Argus, 8 October 1881.

- Ward A & Donnelly A., (in association with the Australian Railway History Society) Victoria’s Railway Stations: An Architectural Survey, Volume 1: Introduction and Summary, March 1982.

- Ward A, & Donnelly A., ibid.

- From early photographs it appears that South Brighton (Moorabbin) had at least some features of the Cheltenham Style

- Davies and Batty’s tender for the Cheltenham Station was £729. 10s.

- Trains had a crew of two, a driver and a guard who travelled in the last carriage. Each station had a team of porters who were responsible for the sale and dating of tickets, as well as signalling the guard with a white lamp to inform him all passengers had either joined the train or alighted safely. When the train was ready to depart the guard signalled the driver with a green lamp authorizing him to proceed with their journey. These lamps were powered by a wick soaked in kerosene and kept and maintained in the lamp room of the station during the day.

- Ward A & Donnelly A., (in association with the Australian Railway History Society) Victoria’s Railway Stations: An Architectural Survey Volume 1: Introduction and Summary, March 1982. page 89.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 4 May, 1889.