Ernest Stanley Gould: Prisoner of War

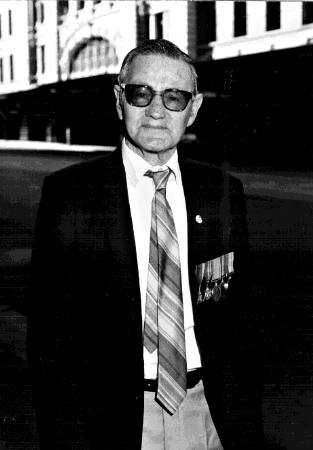

Ernie Gould. Courtesy Ernie Gould.

During the Second World War the local newspapers occasionally reported the death or the capture by the Japanese of men and women servicing in Australian military forces. In June 1943 it was estimated that thirty men from the Mordialloc municipality were prisoners of war. [1] Sometimes they were simply listed as missing and it wasn’t until fighting ceased that the true situation was known. Sapper L Kealy, Sergeant Norm Halliday, Private Herbert Darby, Corporal Harry Mitchell, and Private Leo Martin were amongst this number. There were men from other suburbs in the municipality also involved and Private Ernest Gould was one of those.

Ernest Stanley Gould, a grandson of James Goold, a pioneer of East Brighton, was born in Ormond on 13 May 1917. [2] He was working on a farm in Yarram milking cows until 1939 when he joined the army. Enlisting in Melbourne, he was assigned to the infantry; 2/21 Battalion of the 23 Brigade of the 8th Division. After training with limited and inadequate equipment at Seymour and Bonegilla, he left with his comrades for Darwin on 23 March 1941. On 9 December 1941 the 2/21, known as the Gull Force, embarked on three small Dutch coastal ships, the SS Both, SS Valertyn and the SS Patras, each retaining the stench of recent animal cargo, for transportation to Ambon. They arrived eight days later. The Japanese marines made three major landings on Ambon on 30 and 31 January 1942 and attacked in strength. The Dutch force of 2,600 surrendered on 1 February and the main force of Australians were surrounded and surrendered a few days later. Thus began a captivity that lasted three years and nine months.

Harrison, a medical orderly with the 2/21, wrote in 1988, ‘Who could imagine what sad and bitter reflections were in the minds of these men … their bodies tired, hungry and bruised as they now found themselves being dominated by peculiar looking small individuals, dressed in untidy-looking green uniforms, all excitedly roaring, bellowing and grunting orders at them that they could not understand.’ [3]

Initially the work the Japanese demanded was not arduous and food was available in reasonable quantities; rice supplemented occasionally with small amounts of fish and vegetables. For several months the Battalion’s stockpile of army rations of flour, sugar and tinned food was used together with sugar, sago, fruit, eggs and other food purchased from the local population. Beaumont reported another source was scrounging or stealing from the Japanese. ‘Stealing became such a way of life that some of the Gull Force doubted whether they could ever be trusted to walk through Woolworths again on their return to Australia.’ [4]

The general health of the men for the first two months was reasonable although increasing numbers of them became severely affected by tinea on the feet and around the crotch, causing great agony. Proper medical treatment was not available and the Japanese ignored frequent requests for the most basic items. The only chemicals at the camp R.A.P. for this insidious skin disease were iodine, triple-dye, mercurochrome and formalin, all of which, when applied to the scrotum, caused the patient to fly out the door, and squat on the ground with legs wide apart furiously fanning his burning genitals in a vain attempt to gain some relief from the drastic effect of this dubious treatment. [5]

On 15 October 1942 it was announced that the prisoners on Ambon were to be divided. Two hundred and sixty three Australians and almost all the Dutch prisoners were to be moved to a convalescent camp at an undisclosed destination where medicines and treatment would be available. Ernie Gould was one of the prisoners travelling for eleven days on the Taiko Maru, a dirty little rusty vessel of about 3,000 tons, where they were crowded into holds in distinctly unpleasant conditions. Sea sickness compounded the problems of dysentery, and the latrines were a primitive platform suspended over the stern of the boat. Ernie had swapped the trip with a mate who didn’t want to go. ‘I got the best end of the deal,’ he reflected. Those who went to Hainan Island, the destination of the Taiko Maru, suffered a much lower death rate than those who remained on Ambon. Of the 263 Australians who went to Hainan 181 returned home. Less than a quarter of the men left on Ambon were still alive three years later.

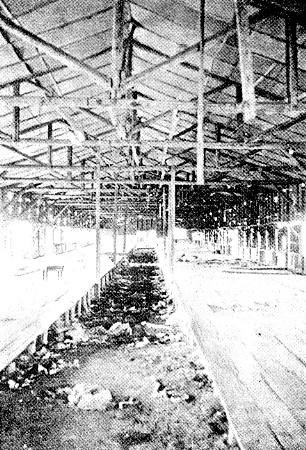

The camp compound at Hashio on Hainan Island covered about ten acres and was surrounded by a low barbed wire fence. The prisoners were accommodated in large huts constructed of walls consisting of wooden shutters acting as windows and roofs of rusted sheets of iron with many holes. The Japanese provided a heavy mosquito net, a thin cotton blanket, a pair of thin cotton socks, a small piece of soap and one issue of very mouldy cigarettes. [6] Ernie recalled the platforms on either side of the hut where they placed their flat straw mats to sleep. Despite continual efforts by the Australians to clean their bedding, Beaumount pointed out, eventually they had to reconcile themselves to sharing their beds with cockroaches, rats, lice, fleas, bed-bugs and the flies with which the district simply swarmed. [7]

Interior of Prisoner of War huts. Courtesy J Beaumount.

Ernie said ‘We were sent to “convalesce” but when there had to work very hard. Building railways, pushing railway trucks full of iron ore on ramps, unloading supply ships, and going on work parties to get wood.’ Prisoners were also made to construct roads, and carry heavy bags of cement through very difficult terrain. The work was made more physically exhausting because of their weakened state caused by the total lack of nourishing food and the harsh treatment by the guards. The men grew weak with malaria, dysentery, tinea and beriberi. The Japanese failed to provide adequate medical supplies or food. ‘We gathered snails, chased lizards and trapped rats to supplement the seven ounces of rice provided for each meal. A large slug was almost like a three course mean,’ said Ernie. [8] John Devenish reported, ‘Early in the piece the place was infested with rats, big water rats. Within twelve months you couldn’t find a rat on the island. I tell you they’re good too! They’re like chicken, taste beautiful once you get the fur off, skin them and gut them. Put them in the pot and they are delicious. But they eventually ran out.’ [9] By 1945 the men were not only suffering from deficiency diseases – they were starving to death. The rice ration was reduced to three ounces of grain twice a day. Ernie recalled, ‘We traded blankets and clothes to get food and tobacco from the local Chinese. We used pieces of cement bag or the leaves of eggplant for cigarette paper. We didn’t get any Red Cross parcels and I got only one letter and that was when I was coming home.’[10]

The atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August and on Nagasaki on 9 August. The cease-fire was announced six days later. It was on August 25 that the prisoners on Hainan were told about the declaration of peace. ‘When we were told it was over there was a lot of cheering and laughter. The boys felt like doing them over.’

‘On return to Melbourne I was admitted to Heidelberg Hospital with several others. I was suffering from beriberi.’ Eventually Ernie left hospital but he took a while to settle down taking various jobs including grape picking in Mildura. [11] After his marriage to Doris Green in 1950, he joined the PMG laying telephone cables and worked there until his retirement fourteen years later. He was in and out of hospitals until his death.

Ernie Gould at a family wedding. Courtesy E Gould, Kingston Collection.

Footnotes

- Mordialloc City News, 15 June 1943.

- Members of the family disagree about the spelling of their surname however official documents and James’s gravestone use the Goold spelling.

- Harrison, C. T., Ambon Island of Mist, 1988.

- Beaumount, J., Gull Force: Survival and Leadership in Captivity 1941 – 1945, Allen and Unwin 1988.

- Harrison, C. T., op. cit. page 100.

- Harrison, C. T., op. cit. page 199.

- Beaumount J., op. cit. page 154.

- Whitehead, G. J., Interview with Ernest Gould 1995.

- Nelson , H., P.O.W. Prisoners of War: Australians Under Nippon, Australian Broadcasting Commission. 1985. page 90.

- Whitehead, G. J., op. cit.

- Whitehead, G. J., op. cit.