Jack Buntine: Gallipoli Veteran

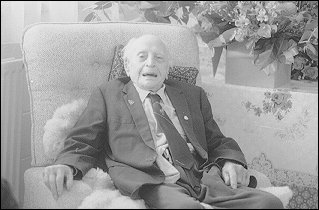

Jack Buntine.

The odds against Anzac Gallipoli veteran Jack Buntine living to a ripe old age were high indeed. A born risk-taker, he always thought he would die young and with his boots on.

But when he died peacefully in December 1998 at the grand old age of 103 he would have been the first to admit that, despite great odds, he had enjoyed “a fortunate life” as fellow Gallipoli Digger Bert Facey described his own charmed existence in the classic autobiography of the same name.

Like many Gallipoli Diggers, Buntine’s hair-raising and accident-prone life would also have made a gripping autobiography. His mother died when he was nine. His drunken father beat him until he was 10 before selling his unwanted son to German market gardeners at Victoria’s Lakes Entrance. When his new foster mother also began to beat him, Buntine escaped to the bush, living “on the run” with Aborigines “huntin’ for tucker” in Gippsland.

He heard about the call-up and enlisted. “I was never one of your ‘king and country’ blokes,” he said in a recent interview. “I only joined up for a bit of fun - and I heard you could get a square meal.”

“I was a good shot too,” he added, “and could knock a jam tin off a fence post at 100 yards, so I reckoned I could help out.”

After training near Melbourne, he sailed to Egypt with the 8th Light Horse. Being a landlubber, he slipped on an oil spill on deck and broke his pelvis in three places, damaging discs in his spine.

Soon after landing he contracted dysentery in Cairo. Dispatched to Anzac Cove he just made it ashore despite enemy fire which killed 8709 Diggers during the nine-month Gallipoli campaign. But no sooner had he started work as a sniper, “taking care of Johnny Turk”, than he contracted enteric fever and was invalided to England.

Assigned to the Middle East Signals as a reluctant batman, the frustrated foot soldier deliberately staged an accident, tipping soup down an officer’s neck, and was promptly banished to the Western Front.

He drove trucks loaded with 4th Division artillery guns and ammunition to the front and backloaded wounded soldiers to hospitals behind the lines. From 1916 to 1918 he served in most of the bloody battles along the Somme River, where another 42,000 Diggers were killed in the stalemated trench warfare.

Then on August 8, 1918, General John Monash launched the first successful assault of the final series of battles for the Somme that finished the war. Monash was knighted by the king and Buntine won the Military Medal as one of thousands who helped turn the tide of the war that day. It was a battle later described by the German army commander, Erich von Ludendorff, as “the blackest day in the history of the German army”.

Buntine won his medal for “conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty at Morcourt delivering stores and rescuing men under continuous fire”.

“I suppose I was pretty lucky,” Buntine mused recently, “but you know, I never worried about getting hit.” It was just as well because by the time peace was declared on November 11, 1918, he had managed to avoid hundreds of bullets. None had his name on them.

Taking risks in life is recommended; after all, you might be killed crossing the road - but the risks that Buntine took demonstrated a devil-may-care attitude. “Oh, we used to go swimming’ at Gallipoli and they would be shootin’ at us. You’d see bullets goin’ in the water around you - but they didn’t worry me. Johnny Turk was not going to stop me swimmin’.

Buntine, a larrikin to the last, loved to boast about daring forays he made against regulations over the top of trenches to rescue wounded mates or to swap cigarettes with the Turks. He never dodged a bullet or shirked a dangerous rescue, he was just incredibly lucky. He was also lucky to survive the post war influenza epidemic that killed 11,000 Australians, including many returned soldiers.

After marrying he survived the Great Depression by going bush again working as a trapper, shooter and gold miner. His first wife died of peritonitis at the age of 31, leaving him to fend for two children.

A risk-taker to the last, he got a steady job with the Post and Telegraph Department, climbing up telegraph poles and driving maintenance trucks on hazardous unsealed bush tracks till he retired. He married Jean Findlay during this period and they had four children.

Decades after most of his mates had died, Buntine lived on in peace, savouring his memories in a Parkdale nursing home where few knew of his heroic background. Here the old larrikin with a twinkle in his eye loved recounting tales, not of his heroic feats, but of tricks he got up to at Gallipoli when the officers were not looking.

Sitting quietly in his room of memories with his wife knitting beside him, Buntine epitomised the traditional saying “old soldiers never die, they just fade away”. Earlier this year he was awarded the Legion of Honour by the French Government. There are now just six Gallipoli veterans remaining: Roy Longmore, 104 and Walter Parker, 104 (Melbourne), Fred Kelly, 101 (Sydney), Frank Isaacs, 102 and Len Hall, 101 (Perth), and Alex Campbell, 99 (Tasmania).

Buntine is survived by his second wife of more than 60 years, Jean, his six children, 19 grandchildren and 22 great-grandchildren.

Footnotes

- Jack Buntine and his family moved from Northcote to Aspendale in 1966. For many years he lived in Station Street, Aspendale. During that time Jack would join other veterans in the Aspendale-Edithvale RSL Anzac march. In his later years he would ride in the fire-truck but earlier he was often the parade leader.