Houses of God

At ninety, Bob Robertson, a lifelong resident of Chelsea Heights, remembers Sunday School. “I got a prize for attending forty five times in a row and not missing a bloody day. It didn’t do me language much good but a bite of churchifying didn’t do much harm either." [2]

The pioneering efforts of members of differing denominations to build, maintain and develop their churches is evidence of a hunger for the comfort of religious faith in the face of constant struggle.

The Heatherton Methodist Church celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 1909 by building a new timber church to replace the original stone structure that was no longer big enough to accommodate the growing congregation. The new building cost £199 and was financed by an overdraft at the English, Scottish and Australian Bank (E.S & A). The original building was retained for use by the Sunday School. At the opening of the new church on July 25th the admission to the function was fixed at one shilling for adults and nine pence for children. Sir Thomas Bent was among the dignitaries who were present that day. [3]

In 1905, Catholic services were conducted in the beach home of Joshua McClelland in Chelsea. As more families came to the area, services were held in Hoadley’s Hall, which was know as the Joss House. On Sundays Joss House was the venue for Catholics at 8 am, Methodists at 11 am, members of the Church of England at 3 pm and Spiritualists at 7 pm.

Tower of the Joss House, Chelsea.

In 1891, Father William O’Hagan was appointed to the Catholic Parish of Frankston, which extended from Chelsea to Sorrento and across to Phillip Island. In 1896 he built a little wooden church in Mornington, called St Macartan’s. In 1911, when a more substantial brick church was built, the wooden church was sold to the Church of England for £55. It ultimately became St Barnabas’s Church, Seaford. When loaded on to timber jinkers, drawn by teams of bullocks, it was impossible to negotiate Olivers Hill so it was taken across to Hastings and down the unmade Hastings-Frankston Road to Carrum Downs until it was moved to 100 Nepean Highway, Seaford. A weekly collection was taken among the settlers of Seaford and Carrum downs to pay for the building. [4]

The original Carrum Methodist Church was built in 1900 by J H Searle for £70.11.11. As the builder made only £3 profit for himself and his partner for six weeks work, the Circuit agreed to give £5 to the builder and the Carrum people did the same. [5]

The first quarter of the 20th century was a period of growth for congregations across the denominations. For example, St Columba’s Church of England in Edithvale held its first service in a private home on May 3, 1912. There was an attendance of 60 and the offering was £2.4.3. The church building was completed in 1913, at a cost of £324. It was not until 1920 that the Salvation Army held its first meeting in a tent on the foreshore. The first officers lived in an iron hut, with tent for a bedroom. [6]

The churches were vital elements in the growing community.

When Mary Chapman met her husband to be, her father “was a bit worried because he wasn’t a Catholic." She describes the feeling in those days of “bigotry. Shocking bigotry." At the time Cheltenham area had no Catholic Church. Looking back on her own happy marriage, Mary remembers that “the relations that used to come out from town said, ‘If Mary’s mother was alive she would never had been allowed to marry this chap’. But Dad said, ‘I trust Mary.’ Anyway, we lived very happily. Brought up six kids. He wasn’t a Catholic but he’d often come along with us. He left me with it and we brought the whole damn lot up Catholics … and sent them to Catholic schools and I know that his father and mother probably didn’t want him to marry a Catholic." [7]

Of her childhood, Mary says, “We attended the church in Mentone then. We went in the jinker with my uncle and my father. After Mass it was real fun. There’d be a big circle of us all chatting away and my brother, who was a bit of a wit, would say, ‘Long live the Kellys!’ that was our name. It was a great opportunity to meet with people.

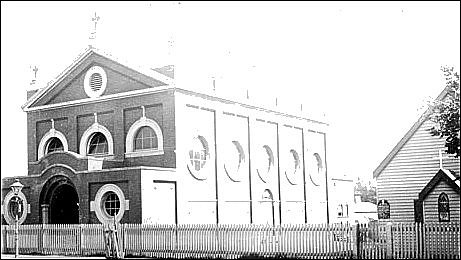

St Patrick’s, Catholic Church, Mentone.

Former banker, Phillip Coffey, has lived all his life in Mentone. His family has been associated with St Augustine’s Anglican Church for over one hundred years. In the early part of the last century the clergy, of course, using horse-drawn transport. Phillip also knows that his “father and Uncle Jack, conscientious and decent young men, you know, went and conducted services even in somebody’s garden or front parlour or shed at the back." He also remembers that, in those early days “there wasn’t the social life that there is now. Social activities tended to centre round the church. You’d put candle wax on the wooden floor of the Sunday school hall and have a dance, you know. Then they had card drives. My memory seems to tell me that they had everything that could raise a quid. Well, not a quid. There were great discussions as to whether to charge say a shilling or sixpence. [8]

Mordialloc’s Bob Wright’s memory spans more than eighty years. He thinks of the churches of his childhood primarily as “a meeting place for friends. We were never forced to go to church. There was religious instruction at schools where they taught us the basics but, I for one, didn’t follow through much on church activities. I went to Sunday school but rarely went to church. Anybody to do with church was always well regarded." Bob added the comment, “Sometime we’d change Sunday Schools to get an extra picnic day!" [9]

Members of the Tucker Road, Methodist Church off on a Sunday School picnic.

Asked about the clergy of her early days in Chelsea, Joy Telfer says, “They were a lot more friendly than they are today, believe me." [10] Len Allnutt, thinking of his boyhood and his parents’ experiences, recalls, “The clergy were vastly different from now … vastly different. The first thing was their pay, it was very low. They couldn’t afford to pay them very much. They had their houses provided. But they took three services on Sunday. They officiated at funerals and they used to visit people. Everybody that went to church would get a visit from the minister. Particularly if anyone was sick, they’d go to hospitals and they were available at all times. People in distress would just send for the clergyman. He’d come. [11]

May Keeley, of North Clayton, believes “that the role of the church today has deteriorated compared to what it used to be." She believes that the clergy of those earlier days were better at counselling and being helpful than they are today. The churches were centres of social activity. “They used to have their fetes and their dances and their concerts. I remember my sister being in a concert, I was only about five, and we walked all the way from down Main Road, near Whiteside Road up to Clayton Methodist Church. A repeat of All Saints concert was done up there and we had to walk home in the dark no street lights. And then there were fetes … and people used to run garden parties. I was brought up on fetes and garden parties. I can’t stand them now!" [12]

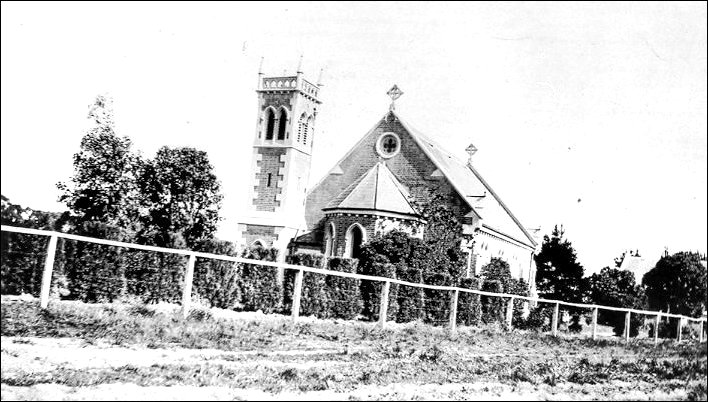

Joyce Peterson has lived a short stone’s throw from Christ Church, Dingley for most of her life. Her father-in-law was Vicar or Christ Church from 1934 to 1945 and her late husband was a Church Warden and Honorary Treasurer. She was a Kindergarten Superintendent and an organist. The picturesque historic church, completed in 1873, was the gift of Miss Mary Attenborough (1819 - 1876) who, with her brother Thomas, came to Australia from Northamptonshire. They bought 170 acres on Centre Dandenong Road for £280 and built ‘Dingley Grange’, named after their English home. [13] During the early part of 1905, a severe bushfire raced through the grounds, burning the ivy covered walls of the Church, including the bell tower, and cracking the bell which was later sent back to England for repair. After much consideration, acetylene gas lighting was installed in 1911 for a total cost of £63, but it was not until 1929 that electric lighting was installed.

Christ Church, Dingley. Courtesy of Mordialloc and District Historical Society.

Mrs Hilda Martin moved to Dingley in 1903 when she was aged 12, and her notes make very interesting reading. For example, she wrote, “If people went out at night they always carried lanterns, and any entertainments planned were ruled by a full moon … On Christmas Eve, Jack Kingston would bring his lorry and horse and, with the organ and the chairs loaded on, the choir would set off and sing a Christmas hymn at the home of very member of the congregation. One house used only candles as they did not trust kerosene!" [14]

Len Allnutt’s family has had a long involvement with the Cheltenham Methodist Church. He recalls, “After my grandfather came to Cheltenham, he married eighteen months later and he and my grandmother went to the church in Balcombe Road. It was a small church known as Zion’s Chapel. It had a burial ground in the yard. Then there was a split in Zion Chapel and the Church of Christ started and then the Methodists started up on their own. The church was on the corner of Weatherall Road and Charman Road (it’s a house now) and then they had a church near the station. That was burnt down one Sunday morning after church. They suspected a spark from a railway engine, but it was never proved. And the, they built where the Charman Uniting Church is now. The building they built is used as a hall now, but that was the church in my time." [15]

“What happened, they had the land there and they were going to build a church onto the weatherboard building, and when the Secretary came up to my grandfather he said to him, ‘Why are you building in weatherboard?’ He said, ‘It’s hard enough to scrape up the money. We can’t afford that,’ he said. My grandfather said, ‘I think you’ve got to look a bit further than that. You build a weatherboard, it’s not going to last long. If you build a brick one,’ he said, ‘It’ll be there when you and I are gone up over the railway line.’ That’s where the cemetery was."

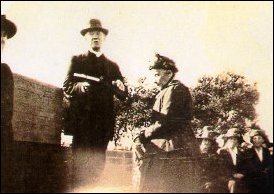

“So grandfather said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. If you’re prepared to build in brick, I’ll double my donation.’ So they had another meeting and it was built of brick. It was opened in 1922, and by 1924 all interest bearing loans were paid with a dear old lady called Grandma Woff meeting the final £100. The Church celebrated its centenary in 1954. The collective effort that has characterised almost 150 years of this church’s existence defies description, but illustrates the value of a church to its members and the community generally." [16]

Mrs Woff lays the foundation stone of the Methodist Church in Charman Road, 1921.

Ken Smith, looking back, says “I have been in very church in Cheltenham now. I started off in the Methodist Church and my daughters got married in the Church of England and my wife was a Presbyterian so I got married there, and I’ve been a couple of times in the Catholic Church." Ruefully, he remembers, “My mother always liked to go to church in the evening, and I was forced to go to Christian Endeavour on a Thursday night after school and that taken by Mrs Boston, and I hated it. I didn’t go one night, and I came home when I should have come home from Christian Endeavour, and Mum asked, ‘Did you go to Christian Endeavour?’ And I said yes. ‘Oh’, she said, ‘Mrs Boston just rang, wanted to know how you were because they said you were sick and couldn’t go to Christian Endeavour’. So I got belted." [17]

It is apparent that the Church, was a source of family consolidation, of social opportunity and doubtless, a comforting belief in a hereafter. These people who needed relief from the mundane, often harsh, reality of poverty, primitive working conditions and limited facilities. The contribution of the Houses of God was an invaluable element in the collective growth of an emerging community.

Footnotes