The Art of Politics

Australia became a federated nation on January 1, 1901. The first Federal election followed in March and the first Federal Parliament was opened in May of that year, with Edmund Barton as Prime Minister. There is no evidence that these historic political events caused more than a ripple in the local area now known as Kingston.

Melbourne Exhibition Building.

Of more local interest was the return to the Victorian State Parliament of Thomas Bent, having been rejected by the voters in 1894. Aged 65, and suffering from diabetes he was soon Premier and also in charge of Railways and the Treasury. His government did not survive a no confidence motion in December 1908, but the by then Sir Thomas continued in parliament, as well as on the Moorabbin and Brighton Councils, until his death on September 17, 1909.

Bent was born at Penrith, New South Wales, on December 8, 1838 and moved with his family to Victoria in 1849. John Allnutt, a fellow councillor at Moorabbin, said that “Bent was Rate Collector for Brighton and then Moorabbin before he defeated George Higinbotham, an English gentleman, by fourteen votes for the seat of Brighton in the Legislative Assembly. The people right down the Peninsular had been lobbying for extensions to the railway line. Bent promised them, ‘Elect me and I’ll get the railway’.” [1]

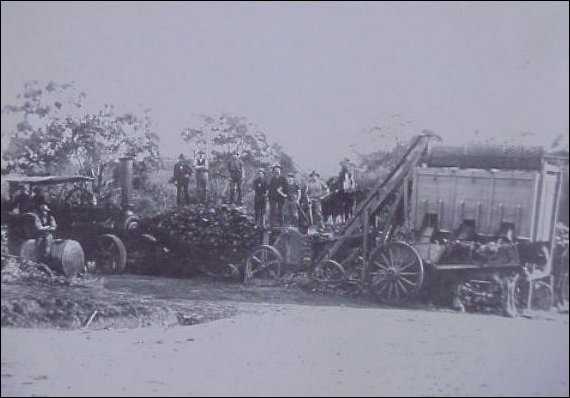

John Allnutt also believed that it was through Bent’s influence and actions that the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum, now called the Kingston centre, came to be in Cheltenham. Len Allnutt, John’s grandson, said “The home in North Melbourne was overflowing with inmates and they had to go somewhere. Tommy Bent represented this area and he obtained some 300 acres or so and the press attacked him. There was a great howl. He ought to be gaoled they said.” Len held that Bent supported the use of the land as the site of an asylum, “because it brought employment in his own constituency.” [2]

Benevolent Asylum, preparing the building site. Courtesy Betty Kuc.

There was also what Len called ‘an episode’ at the Victoria Market involving Tommy Bent. Moorabbin was a vegetable and fruit growing area and it was to the Victoria Market that they conveyed and sold their produce. Trouble erupted at the market about the arrangements for paying for the vegetables. There was no actual connection between the producer and the consumer. The growers had to sell their produce to a powerful group known as the ‘Flinders Street Ring’ of produce merchants who set prices because the stalls at the market were held by them and retail dealers. The growers believed they were crowded out of what they considered their market. As a consequence the prices gained for their vegetables were controlled by the merchants and the growers felt they were too low. [3]

“There were a few blokes amongst the market gardeners who could fight”, Len’s grandfather told him. “And when it looked as though a bit of an argument was brewing the word quickly spread. It became known that if you picked an argument with a grower you were likely to get a hiding. The merchants said they were going to put a stop to this and have a law passed to stop the interference of the growers. At the time the growers were battling and struggling for a living so they had a mass meeting to discuss what they should do. They decided they would go and see the Premier. They would go and see Bent.” [4]

Originally, a deputation of three was proposed but finally Len’s grandfather was the sole representative. He went to Parliament House because he was a close acquaintance of Bent. He told Bent what was afoot. Bent said, “You go back to the market and you tell growers that while I’m Premier of this State I’m not going to bend to any merchants. I don’t care how much pressure they apply. Tell the growers they’ve got nothing to worry about. Bent kept his word.” [5]

Among the many other stories told about Tommy Bent, there is one recorded by Tom Sheehy involving a billiards table. “When in 1901 the Cheltenham Mechanics’ Institute was endowed with a billiards table there was a certain amount of jealousy to be detected in the attitudes of those in political opposition to the benefactor, Thomas Bent. … the rumour was spread that the table had been installed at the cost of the taxpayer … When Tommy Bent’s critics and accusers asked, ‘Who paid for the billiards table installed at the Mechanics’ Institute?’ Bent was in a position to give a simple angelic answer, ‘I did’.” [6]

Bent’s donation of a billiards table had come about following an appeal to him from his friend, Cr Frank Le Page, who was more concerned at the number of ‘pushes’ roaming the City of Melbourne and its suburbs. Locally there was a push known as the ‘Merry Hawks’ who despite the fact that they were feared by some residents were quite harmless. Le Page had discussed the problem with Bent along with other members of the Mechanics’ Institute. ‘We were very much in need of something like a billiards table to keep these young fellows occupied,’ said Le Page. ‘And you shall have one,’ replied Bent.” [7]

Sir Thomas Bent’s influence continued after his death despite the constant criticism and allegations of serious wrong doing that had persisted throughout his forty six years in politics. Margaret Glass notes that Alfred Deakin described bent as “the most brazen, untrustworthy intriguer the Victorian Assembly had ever known.” She also referred to the masterly piece of ecclesiastical diplomacy used by Archdeacon Hindley during his oration at Bent’s State Funeral. The Archdeacon said, “while we may not praise, we may thank God for whatever good was done by him.” [8]

As to local attitudes to government, Bob Robertson, at ninety, has some strong memories and opinions. “It wasn’t talked about like it is now,” he says. “They were decent bloody blokes in them times, you know. I listen to them on this television and if I was going to school and I carried on like that I’d have been put in the bloody corner. They just go there to argue with each other. I know that’s what they’re there for but they rubbish each other there terrible. [9]

Mary Chapman’s political memories of her youth are not strong but she does remember her father and her Uncle Frank, who lived with them, as “dyed in the wool Labour men.” Her uncle would go off to all the parties and meetings. ‘He even learnt to recite so that when they had those little parties he could recite some verse. It was pretty important to them,” she says but she didn’t know whether this was good or bad. [10]

Another staunch Labor supporter was Tess Bone’s father. She remembers one Friday night, when there were elections coming up, there was a soap box out there with a Labor man giving his little speech. On the opposite corner was Abbott’s the grocers, and there’d be the Liberal man. There’d only be the two. And we’d have a meeting perhaps down at the old City Hall, and we (as children) used to get carted to them all. [11]

Local government in the first quarter of the century attracted leaders from the community well known to their constituents. Len Allnutt, whose father served as a councillor in Moorabbin, comments on changing conditions. ‘It was vastly different to today,” he says. “They were responsible for all the roads and all the footpaths and all the street lighting and all the drainage. People would be knocking on the door at night time and Sunday wanting something done. In those days, the people who were councillors knew the whole municipality. Of course they never had anything like the money and it was all voluntary. They get paid today but the men who were in Council in those days - I’m not casting aspersions on anybody - times change, but those men gave freely of their time and money. They’d (the rate payers) have a go at them at public meetings and that sort of thing and they didn’t mind at all. They considered it an honour to do it.” [12]

Between 1900 and 1925 four men served two consecutive terms as President of the Shire of Moorabbin. They were Thomas Bent, W.G.Burgess, David White and Michael Clements. Nine others served the Shire for ten or more years in the same period. Francis Thomas Le Page, with twenty eight years service, was the first of the long serving Le Page dynasty. [13] Charles Gartside, Joyce Peterson’s uncle, was a councillor in the Shire of Dandenong in 1922 and later entered State Parliament as the community’s representative and Minister of Health in the Holloway government. [14] Bob Wright remembers Roy Beardsworth who was a councillor at Chelsea and later represented his community in the Victorian parliament. Bob says, “He was always spoken of very highly. [15]

Three generations of the Le Page family serve on Moorabbin Council. From the Leader Collection.

Despite Federation, government at a national level was remote from most of the hard working people in the district. Long hours, light purses, the demands of church based activities, the care of large families, limited transport and communication facilities may have been among the contributing factors. There were, however, some issues that generated strong responses from the local community. The issue of conscription was one.

At the outset of the war in August 1914 there was a rush to enlist. In the following years enlistments began to decline although with the news of the Gallipoli campaign there was again an up-surge. After the disastrous Some offensives in France with its high casualty rate and huge losses of life the Australian Government agreed to supply more troops. Pressure was put on men to volunteer. Eloquent and stirring addresses were given at local meetings where speakers maintained Australians were compelled to go to war in view of the German objective of world domination. [16] When recruitment lagged Prime Minister ‘Billie’ Hughes believed conscription was justified and actively canvassed this issue. Referendums held on October 28, 1916 and December 20, 1917 were both lost by relatively small margins.

Records and memories of other government actions of the period and their impact on the local community are relatively scarce. In the late 1920’s the spectre of the approaching financial depression menaced the nation. At State and Federal levels, political leaders with the assistance of economists and bankers canvassed a range of hopeful preventative and remedial measures without effect. There is little evidence that their concerns were seriously considered in our close knit community. The challenge to survive, day by day, took precedence.

Footnotes