Nola Barber: Mayor and Councillor

Nola Barber as Mayor of Chelsea. Courtesy of Chelsea and District Historical Society.

Nola Barber is significant historically as the first female councillor (1948) and first female mayor of the City of Chelsea and a foundation member in 1951 of the Australian Local Government Women’s Association, formed by women councillors to encourage women to become involved in municipal government. [1]

I do not know whether Nola would have described herself as a feminist but she was very aware that women’s needs an those of their families would be better met if women were active citizens in the public domain. She worked within the tradition of those feminists and labour movement activities who contributed so much to Australia’s famous post-Federation welfare state by lobbying to achieve, for example, district nurses, pre-natal care, baby health centres, creches, kindergartens, play grounds, the right of widows to have custody of their children, female factory inspectors and police officers and a probation system for juvenile offenders. Nola contributed to the development of Chelsea by working to achieve such amenities as kindergartens (one of which, founded in Aspendale in 1951, was named after her), the first library(the campaign lasted from 1948 to 1972), meals on wheels (which she ran for a period on a completely voluntary basis in order to persuade doubtful fellow councillors that such a service was necessary and viable) and two senior citizen centres. [2] A list of local organisations to which she belonged indicates something of the breadth of her interests. One of her longest associations was with the life saving club where she gave her time voluntarily to teach children how to swim and obtain proficiency certificates.

Martin Shult, Malcolm Rigby and Stephen Lamb at the Nola Barber Kindergarten, in Aspendale, 1963. From the Leader Collection.

Nola was extremely well organised and believed in efficient household management, aiming to get housework ‘out of the way’ early in the day. She welcomed labour saving devices, such as washing machines, which lightened women’s chores and gave them time to be involved in interests outside the home. [3] She was a councillor at a time when women in public life were relatively few. (As late as 1977, only 6 per cent of Australia’s councillors were female). Her presence was bitterly resented by some male councillor. Union of Australian Women member like Eileen Capocchi, secretary of the Library Promotions Committee, who sometimes attended council meetings, were shocked by the lack of civility of men who ridiculed her proposals and passed derogatory asides at meetings. Eileen recalled:

"The councillors were so rude to her. A lesser person would have given it away. She ignored them, just kept going to her meetings. She was so determined. It was almost like a religious zeal with her." [4]

Another reason for male councillors’ hostility may have been that Nola was often working for services, now commonplace, which the municipality at the time did not have. Her persistence may have challenged male councillors who considered that they had done well in life on a personal level and on council. Eileen Capocchi testifies that one made a strong impression on the Library Promotions Committee by stating something like, ‘What do we need a library for? I’ve hardly read a book in my life and look where I am now’ There is evidence that women in government 30 years after Nola Barber retired still face personal abuse from male colleagues. [5]

In some of the causes she espoused Nola Barber was far ahead of much of Australian public opinion. A wish for disarmament and for a foreign policy independent of the great powers were certainly among these. Like most UAW members she was aware that her views were, however, nothing out of the ordinary in Europe or Britain. Thus in 1956 she chaired a UAW sponsored Assembly of Mothers (inspired by a World Congress of Mothers held in Switzerland the previous year for which the Mayor of Lausanne had hosted a formal reception). Attended by 120 women, who listened to academics speak on childhood development, the meeting concluded that war was incompatible with happy childhood and asked for an end to the arms race. [6]

Freedom from Hunger Committee visit Chelsea Council. Cr Barber hands over cheque to Dr Mildren Green. On right of Mayor is Mr Halliday (organiser) and Mrs Dobson From Leader Collection.

Nola was among those in the Australian Labor Party who found it ridiculous that the People’s Republic of China, with a quarter of the world’s population, was not recognised by Australia as the government of China. In 1958 she attended peace conferences in China and Japan. In 1961, when 39 Nobel Prize winner, including Australians Marcus Oliphant, Mcfarlane Burnet and John Eccles, appealed to the USA and USSR to reduce their stockpiles of nuclear weapons, Nola immediately asked her fellow councillors to endorse this appeal. I do not know the result of this move. In the early 1960s, when she was mayor, she welcomed, at a Chelsea hall, those who joined in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament march from Frankston to Melbourne. She would like to have used the town hall but other councillors opposed such an initiative. [7] The Federal government certainly opposed her views. Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation file from the period show that she was under surveillance. [8]

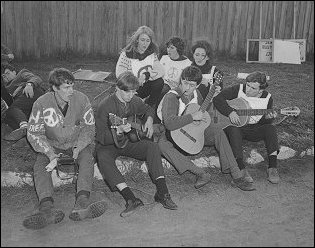

'Ban the Bomb' marchers outside the Elderly Citizens’ Hall in Chelsea 1963. From Leader Collection.

She opposed the war in Vietnam and particularly the conscription of youths not yet old enough to vote. When Save Our Sons was established in Victoria in 1965 to oppose the draft she was unanimously elected president. With a companion, Mrs Ames, she had stood vigil outside the Engineers’ Barracks in Swan Street Richmond, in protest against the draft. [9]

Nola Barber was an ALP candidate for state and Federal parliament at least three times, including in 1961 and 1967 for the Legislative Assembly. [10]

Footnotes

- Fabian S., & Loh M. Left-Wing Ladies: the Union of Australian Women in Victoria, 1950-1998, Hyland House, 2000.

- Discussions with Diana O’Loughlin, December 2000, January 2001.

- Interview with Eileen Cappochi and Molly Hadfield, 1995.

- Fabian & Loh, op cit., pages 106 & 49.

- Interview with Eileen Cappochi and Molly Hadfield, 1995.

- Fabian & Loh, op.cit., page 33.

- Ibid pages 31, 61-2.

- Ibid page 180, Note 26.

- Ibid page 63.

- Smith, Yvonne, Taking Time, UAW, 1988 page 53.