Homemaker, Helpmate, Social Girl

Whether single, married or widowed, women in the Kingston district in the early twentieth century were courageous in the face of hardship and poverty, and committed to making a better life for themselves and the community. They gave up careers to care for large, extended families. Despite heavy responsibilities, they enjoyed a healthy social life even if it meant more hard work to make it happen.

It was an era when there was welcome and radical change in the role of women in Australia. South Australia had led the way by giving women the right to vote in 1894 and achieved a world first, by permitting women to stand for Parliament. After Federation, the new Federal Government of Australia passed an Act extending those rights to women throughout the nation.

Deputation of leaders from United Council for Women’s Suffrage on way to meet with members of Upper House of the Victorian Parliament, 1899.

The vote was not compulsory at this stage, however, and women in the Kingston area at the turn of the century were far too busy tending to large families and creating a viable community to be involved in politics. "There was too much to do at home to start worrying about politics," says Betty Kuc. "I think they had other things to worry about." [1] Rather than solving their problems at the wider community level, Alf Priestly says the family gravitated towards the kitchen to talk. "This was a big part of why families got on so well," he says. "They thrashed their problems out at the kitchen table. The kitchen was the main room of the house in those days. It was a very big kitchen, with a very big table in the middle," Alf recalls. [2]

As homemakers, they had high standards to maintain, as Phillip Coffey writes in Reminiscences: Spring-cleaning was then the trademark of good housekeeping. That expression has now almost disappeared from our vocabulary. In the days of our grandparents it was a necessary and sensible custom. Lace curtains were washed and dried, ironed and aired. Carpet squares were lifted, and 'beaten' on the external wire clotheslines, which hung between posts. It is difficult to appreciate the disabilities under which women folk operated their households prior to the introduction of refrigerators and access to supermarkets. Combined with Spring Cleaning was the practice of `putting down' namely the preservation of eggs in kerosene tins. An extensive display of variety of bottled jams was a visible sign of competence and 'good housekeeping'. [3]

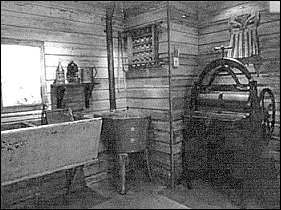

Kath Kirkcaldy says washday did virtually take all day, and as there were no drip-dry things, everything had to be ironed. "If it was wet," she says, "clothes had to be hung wherever you could hang them, in the shed, until they did dry." [4] As there were no take-aways or self-service or anything, women did their own cooking, she says. "With my mother, Saturday was baking day, and she'd be going from morning 'til night. All the cake tins would be full and she'd cook scones, and we never, ever went without a dessert at night; and it was solid, because growing kids needed something solid. Mother made our own (desserts). She'd help dad in the garden with the vegetables and the flowers and of course we grew all our own vegetables, and mum did all our own sewing. She did the mending, because of course, things wore out, and we couldn't afford to buy anything new, so they had to be mended. Socks had to be darned, and by the time your mum had done all that, and made your clothes, and the knitting, there was not a lot of time for getting bored or for socialising," Kath recalls. [5]

The washhouse with mangle and troughs.

In order to care for their families, women stopped working outside the home after marriage. They worked hard at home, however, in family businesses and even in the fields, if necessary. "The woman's place was in the home. And bringing up children," says Jean Martin. "When women married in that era, they simply didn't work." Her brother Len Le Page adds that their mother was a tailoress before her marriage, travelling to the city from Cheltenham by train. After she was married, Len and Jean's mother had five children fairly quickly, and she had a big job looking after them all as well as feeding the men in the paddocks. "She used to make morning and afternoon tea and lunches for them," says Jean. "The men would come in for lunch at mid-day, and then she cooked dinner at night. It was a full time job, just being a housewife," she explains. [6]

Bob Wright remembers that the attitude towards women was one of great respect for their hard work and their ability to lend a hand where necessary. "She was the housewife," he says. "She looked after her children. No matter how many there might be... and in most cases there were quite a few. A woman's life was quite hard. I think that they were all respected. I think that if any boy or girl were disrespectful to a lady his father would give him a fair belting. That happened with us, I know. We were taught to respect women." But they were very hard working, he says, and maintains that his mother was no different from most others in being a true helpmate when necessary. "She looked after a small business while Dad was away, carried out the household chores and brought up seven children at the same time," he cites as an example. [7]

Frank Baguley's wife was a wonderful help to him in his flower growing business throughout their marriage. "My wife helped me one helluva lot in the early days after we were married," he maintains. She picked flowers... helped me to clear the block and saw up the trees, some of which were five feet across. She helped me do all that," he says with pride. [8]

Even though the mother was a central figure in the family usually looking after the budgeting for the household, she sometimes did not have a penny to herself. Joyce Peterson says that in fact, the little woman had nothing. "She didn't have a penny piece to herself," she says. "Usually you had to account for what you spent your money on." She also recalls that her Aunt Hilda (Gartside) was particularly hostile about the fact that even though the girls in her family had to go out and get a job, they had to bring their money home to support the Gartside boys, who were developing their cannery at the time. [9] “Without Aunt Hilda and the girls' contribution, it may never have happened.”

Grandmothers offered comfort and home cooking. Sylvia Roberts remembers the rewards of the long trek to her Grandma Mills' place in Heatherton. "When we used to go over to grandma's she had a little side bread oven, and we used to walk over from Palm Road in Cheltenham to Heatherton, with Margaret in the pram. It was a long, long, walk, and when we got there she would make us homemade bread. She'd make us little loaves each of this brown bread, and then we'd have homemade apricot jam on it, and clotted cream. We'd scoop it off and put it on the bread. This was our lunch, and we thought it was beautiful! Grandma had made us little fresh loaves each... On our way over, Uncle George lived on Heatherton Road, and we'd call in there for a cool drink and a cuppa, and off we'd go again. I often think the miles we walked to see grandma." [10]

But grandmothers knew where to draw the line. They set their limits. "When we'd get there, Grandma would sit down, and she'd put her feet on a stool, and she never did another thing until we left," says Sylvia. But even though they had walked such a long way, the girls would have to serve and do the dishes while her mother and grandmother chatted, she recalls with a smile. [11]

In the absence of Social Service, women often had to look after the poor and unfortunate in the community. Jean Martin remembers that her mother used to provide sandwiches for the inmates of the Melbourne Home for Men, when they drank so much that they didn't make it back to the Home on time. "The gates were locked, at six o'clock at night, so they'd sleep on the side of the road, and then they'd come and want food at eleven or twelve o'clock at night." [12]

Joe Souter says that his mother also fed the Swaggies and Remittance men who called at their home from time to time. "Because we lived opposite the church property," he says, "Mum was forever baking scones or giving them a bit of beef or meat to eat. If they didn't get it there, they'd go on to the next house to eat. They'd call regularly. They had their own times every year," he recalls. [13]

There was no organised help for the sick and the infirm in those days and women were expected to take on the role of carer. "It was self-help within the family," Tess Bone says of her day. [14] Jean Martin agrees. "As well as raising six of us at home, Mum looked after our Grandmother, her mother-in-law, who was bedridden from 1927 until she died."[15] "Families looked after one another," adds Jean's brother, Len LePage. "And they also looked after a lot of other people. But everyone helped one another in those days. They didn't just look after themselves." [16]

"You would have your grandparents when they could not live alone. Everyone just accepted it", says Len Allnutt. "There was none of this putting them into a home in those days." He concedes that people did not live as long but says that they were still incapacitated, on walking sticks, and could not get around. "There were no hip operations in those days," he says. [17]

Unmarried women, and there were usually more than one in the family, shouldered the responsibility of care for the family in times of emergency. They also worked throughout their lives. "Spinsters," says Len Le Page, "worked on for many, many years." Women of his mother's age, such as the McKnight girls for example, never married, and worked in the newsagency all their lives, he recalls. [18]

"Well, I think the maiden aunt, she was the one who was taken from one place to the other to fill the gap. She didn't have much say in anything but she was always there - to take over the role. Say something happened to the mother, she took over that role," says Joyce Petersen. [19]

"In those days, lots of families had unmarried daughters" says Len. "It would not be uncommon to have two or even (three single girls) in the family. My own grandmother was ill for quite a while before she died. Her youngest daughter was a nurse, and married, with a family, but they just lived with grandmother, and looked after her. Nobody thought anything about it." [20]

There were widows who had the task of bringing up a large family of children on their own. They had to do this without the benefit of education and training for work, which means relying on work such as cleaning, washing and ironing. Len Allnutt remembers that his mother and grandmother employed women who needed to support their families, to help with household chores. "There was no social service in those days. Washerwomen were common. A woman would work regularly, for one or two days (a week). My mother always had a washerwoman. She had one for years and years. A washerwoman and a cleaning woman - nearly all the families had one. Some of them would only be young girls, who could not get a job, and they would come in and do the housework. But a lot of the married women with families, if their husbands were ill, or if they were widowed would not work full time. (They) would have maybe two or three places to which they would go each week...that was quite common. That's how they dealt with poverty in those days," he recalls. [21]

The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum, which was moved to Cheltenham from North Melbourne in 1911 at the instigation of Tommy Bent, says Len, provided many employment opportunities for women in nursing and domestic services. [22]

Working in the Laundry at the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum. Courtesy Len and Dorothy Allnutt.

Nursing, teaching and secretarial work were the professions to which young women aspired. Others went into clothing, either in sales, or as dressmakers. After leaving school between the ages of 12 and 14, girls were also expected to help at home, in shops and businesses usually run by their parents. Some had little opportunity to choose to do the work they wanted; others made the most of their lot in life, while others still, managed to do what they really wanted after a while.

"I think they (girls) were very suppressed," says Betty Kuc, "and they didn't have any opportunities. Even when I wanted very much to be a nurse, my father wouldn't allow me because he had worked as a night orderly at the Caulfield Hospital in the early days when he was developing the business. He saw what the nurses had to do, and I don't think he wanted his only daughter to do that," she concludes. Her mother on the other hand, she says, was very popular in her parent's guesthouse business, making constant cups of tea, doing the tables and that sort of thing. [23]

Kath Kirkcaldy would dearly have liked to be a nurse, too. "I was always bandaging up the cat, or chook or something. I didn't mind other people's blood, as long as it wasn't mine. No, I think that probably was my (desire). Most girls would like to have gone into teaching. That was the main thing at the time. If you were good enough you became a teacher. If not, then you worked in a shop, or did a little bit of domestic work. When I was in my final years, there was not a lot of domestic work going. It was factory work, shop work or the academic, but mum and dad couldn't afford to put me through nursing. They were just hardworking people and as such, couldn't accumulate a lot of money," she says. Kath ultimately went to High School where she did very well, and completed a commercial course.[24]

Matron at the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum. Courtesy Len and Dorothy Allnutt.

Myrtle Squire became a teacher, remained unmarried, and worked all her life, committing herself wholeheartedly to teaching school during the week, and taking Sunday school classes in and around the district at the weekends. Myrtle remembers that her younger sister Lillian wanted to become a dressmaker. After she left school, says Myrtle, Lillian helped her mother, and aunts and cousins as the need arose for some twelve months or so. In 1916 she was still keen to do dressmaking and went to a firm in Mentone called Abbott and Mason to work for a lady who had advertised for a girl leaving school to learn dressmaking. "That was just the opportunity mother wanted for Lillian," she says. When Lillian went to Mentone, she soon established herself as a very good seamstress, with very good ideas, despite the fact that she had been unfortunate enough as a child to have a serious eye injury, Myrtle recalls. [25]

Jean Mitchell remembers that for her mother, the ultimate expectation was to be virtually a housewife, and if she could find any- to work- because quite often the men found it difficult to find a job and it needed both parents to pull together, in order to survive. "I remember mum had a very old drop head Singer sewing machine, and if we wanted clothes, she would usually make them at night time," says Jean. But Jean's mother wanted more for her daughter. "When it came to that, mum wanted me to go to high school because she wanted me to be a teacher. Dad didn't want me to go to High School because he wanted me to help him on the poultry farm, and mum put her foot down, so I went to High School," she says.[26]

Due to the lack of hospitals and consequent number of home births, midwives were in high demand. Families were large. Women gave birth either at home, or in the home of a midwife. Sylvia Roberts remembers that her grandmother, (Hannah Porter, who married Broderick Mills -known as "Saltbush Bill") had eleven children. She recalls, that generally, a midwife usually a neighbour would attend the birth. "They'd get the doctor sometimes," she says, "but usually they had the birth at home." [27]

"They'd get oodles of brown paper, so that none of it would get on their beds, and they would prepare for it in their own way," she says. Jean, her oldest sister was the only one of her siblings born at home, and all the rest were born in midwives homes. Midwives sometimes worked from their own home, or they stayed with the mother until she was able to look after the child, Sylvia explains. "They would have a room where they delivered babies," she says. "They were just midwives - wives who delivered babies." Her grandmother, Granny Liddell used to ride for miles, she says. She would be taken to the farms, stay there, and be collected four or five days later. In the meantime, she would deliver the baby, care for the family and she stay with that family until the lady was able to feed her baby on the fourth or fifth day, when the milk came. She did that for years and years, old Granny Liddell," Sylvia recalls. [28]

The Liddell Family, 1910. Seated: Emma Liddell- nee Bloomfield (Left to Right). Standing, Tom Liddell, Alice Evelyn (Dolly) and Norman Charles Liddell. Courtesy of Alf Liddell.

Somehow, these busy women still found time to be active in the community. They were on Ladies' Auxiliaries associated with churches; sporting clubs; environmental groups; schools; and in national bodies such as the Red Cross, fundraising for local community needs, the environment and in supporting political causes.

Joy Telfer's mother, Bertha Armstrong not only looked after the family and later her grandchildren, but was involved in the Red Cross and St. John's Brigade, the Mother's Union, and involved with politics possibly up to the time that Mr. Menzies was running for election to the Legislative Council, East Yarra Province, in 1928. His handbills for the election listed twenty-five electoral committees, covering every important suburban centre, which stretched from "Kew and Toorak through Box Hill and Camberwell to Oakleigh."[29] (As the Armstrong's had moved to Camberwell at around this time for her husband's health, Bertha could have been involved with the Camberwell electoral committee). [30] "Oh yes. Mum never sat still if she could move around," says Joy, of Bertha Armstrong. "Lord Bruce, I can remember him coming to speak to the ladies here, and I can still see him putting his hand in his pocket, and pulling out- (well it'd be twenty cents nowadays), a two shilling piece and looking at mum, looking at me, and putting it back in his pocket, saying, 'listen, no, I'd better not do that'," she remembers. She also recalls her mother's devotion to Mr. Menzies, and his ideals. "If Mr. Menzies asked for gold or anything like that, she'd give him the gold out of her teeth!" she says. [31]

Mrs Armstrong (centre) with the Rev C T Holloway, vicar of St Aidan’s Anglican Church, Carrum and Miss Nellie Somerville at the last service in the old building prior to the construction of the new church. From the Leader Collection.

Joy Telfer's grandmother, Mrs. William Black, had a great head for finances, and was treasurer and founder of St Aidan's church. Before it was built, she ran the church from her home. "Mum's first marriage was at St Aidan's at Carrum, which grandma was responsible for being treasurer and prior to that I think Grandma had church in the home next door,” Joy recalls. [32]

Norm Stephens remembers that his mother was a real worker on committees. "Oh mum was involved in the club which ran things for the local hall, to keep it going. She belonged to the bowling club, in the ladies' committee there. Mum, like dad, if they belonged to anything, they would be there working. Out in the kitchen, and doing all the things that women do at these functions," he says. [33]

The Smibert Family. Courtesy of Don Smibert.

There was concern for the environment even in those days, and Don Smibert's grandmother Clara Evans was a Guardian of the Foreshore in Chelsea around 1920. "In those days you had to protect the foreshore. If people did things which might destroy the plant life, there'd be warders who raced down to say 'Hey! Hey! Get away from there, you mustn't do that'. They kept it pretty natural. There was more of that wiry grass that grows on the beach, and honey suckle and tea-tree down there and if people went to cut them down to make fires or things like that she'd say, 'Use what's fallen'. They protected the beach, mainly from any vandalism," Don explains. [34]

The Guardians of the Foreshore Badge. Courtesy of Don Smibert.

His grandmother Clara Evans, says Don Smibert, was also involved in the Red Cross and other charities. "She was a volunteer, I don't think she actually joined as a member. But mum was with the Spastic Society. She was a life member of that and she worked with a lot of these different organisations at the time." [35]

Len Allnutt mentions that even though his grandmother did not belong to anything, she just worked hard all her life. "She was heavily involved in this poverty business and all that sort of thing. Always tried to help people." His mother, however, was always involved in public life. She was a foundation member of the Moorabbin Blind Institute and the Baby Health Centre, and she had the 70 Year medal for the Red Cross. She was also involved in the local Benevolent Fund or Society, which was part of the State Relief. Len remembers that the family was very worried about the visits she had to undertake to evaluate the recipients of this fund, which often led her into strange territory. The State Relief had branches all over the State, he says. Dame Phyllis Frost was the Chairwoman. [36]

Joe Souter encouraged his wife to take on the responsibility of Secretary on the Dingley Reserve Committee, which was formed to make money for a reserve. "Joe who was the President said to me, 'What about me taking on the secretary's role? I said I've never done a Secretary's job. I'm not doing that!" says Betty. But Joe had faith in her ability. 'You can do it." I'll help you with it,' he said. He said 'It's better to have a woman. You don't want all men on it.' Anyway, under sufferance I took it," she says. And they did a wonderful job together on the committee, establishing a highly successful sporting venue now known as the Souter Oval. [37]

Life at the turn of the century was hardly dull, according to Bertha Armstrong. Even a humble train ride to work yielded new friendships, and Bertha describes that among the very first travellers on the train from Aspendale station to the city in 1907, she met Mr. Thomas Symons, buyer and publisher for Geo. Robertson's Book Store in the city. [38] “The time passed very quickly, as he had more books to read... than he could manage, so he passed some onto me,” she writes. “Also at his home, I met C.L. Dennis and E.J. Brady and some other men well known in the publishing world today, but then at their beginning.” [39] Another passenger on the 7.35 a.m. train was Alderman Burton from the Melbourne City Council, who had a seaside house in Edithvale, and a townhouse in Cardigan Square, Carlton. Of him, Bertha writes, “His drags and beautiful horses were very popular for picnics in the Livery Stables in Latrobe Street. The side of each drag was painted a different tartan." [40]

Everyone made sure that they had time for socialising, with or without their partners, and if it served the community at the same time, so much the better.

Alf Liddell says that his mother just loved Euchre parties, many of which were connected to charitable organisations. "My mother used to try and sneak off to Euchre Parties. Just to stay sane. She often used to win. She was very cluey with her knowing where the Jack and Ace, and where the other cards were," he says. "They (the card parties) would be (held) in a hall or a private home. If it was for a charity, most probably in a private home. Or we had Mechanics Institutes in Cheltenham. She went there, and the rest were run in private homes. They'd have their special charity. Some woman with a bit of money would support a private charity. They had a lot of ladies, about twenty-five or twenty ladies, or so. Mum liked cards. She played 500, and Euchre. That's all. She didn't play the richer ones, like Bridge and that. That was for long cigarette holders," he says. [41]

Concerts and Sing-Songs were all the rage, and Dances were big!

There was a big concert hall at the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum. "All the Domestic staff and the nurses would have a Fancy Dress Ball, or a dance or a card night, or something," says Len Allnutt. "They were more or less isolated, and they had this great big hall, so they could hold the functions in the hall you see, and they would make their own entertainment."[42]

Nurses in Fancy Dress at the Melbourne Benevolent Society Asylum. Courtesy of Dorothy and Len Allnutt.

"Mum and Dad both sang," says Tess Bone. "They were both in the choir in the church. We had a minstrel show, and a big concert down in the old City Hall. And on Sunday nights, we would all go over to my Mother's sisters. Both my aunts played. So, around the piano we would have a sing-song," she recalls. [43]

"Mum and Dad used to love their dancing, "says Norman Stephens. "They raised money to buy a piano at one time. I used to be dragged along there. They used to work and dance, and as a little kid I used to sit on the step and watch them."[44]

Homemaker, Helpmate, Social Girl. That's the way they were, these women of Kingston.

Footnotes