The Spirit of the Community

One day, about seventy-five years ago, Cuddy Brownfield was working in a back paddock of his dairy farm, which was on land now occupied by the Moorabbin Airport. He could see his wife, Gladdie, near the house but their little boy and girl were not in sight. He concentrated on his work, thinking how fortunate he was. Shortly after, he heard a piercing scream. Gladdie was running towards the house as it burst into flames. Through the billowing smoke he could just see her go in the door where she disappeared. Cuddy raced towards the blazing inferno, too late to save his wife and two children.

Joyce Peterson, of Dingley, vividly remembers this tragedy, although she was only about five years old at the time. Little Bruce Brownfield was her playmate. She knows that all the people spontaneously helped Cuddy in their own unique way because, as she recalls, that is what happened automatically in such terrible circumstances. It was characteristic of the people and the times. She believes that this ethic of mutual help was born of socio-economic factors. “We were all poor,” she explains. [1] Mary Chapman and her family were near neighbours. “It nearly killed us, you know. We used to look after the children when she (the mother) went off to play tennis. The little boy was sent, with the pram and gave us the baby and we didn't mind minding the baby for her. We wanted to help and so did everybody else. My neighbour over the road, Mrs Mills, rushed off to see what she could do. But we were all so desperately sad about it, you know.” [2]

As well, as Cheltenham's Ken Smith recalls, “Everybody knew everybody.” [3] The physical size of the community, may well have been a contributing factor influencing community cohesiveness. But there were others.

Clearly, the family was absolutely central to the whole community. Families were generally larger, with ten or twelve children being not exceptional. Many were born at home, sometimes with the assistance of a midwife or a neighbour. Bob Robertson, of Chelsea Heights, looks back down his ninety years when he remembers life as a member of a family of ten children. His father's income, during much of his childhood, was about “five pound a week” from working on the roads. Nevertheless, by dint of having a vegetable garden, a cow and a few chooks, they managed. When, on Sundays, friends or relatives would come for a meal, his mother would see that they all had a good plateful. If asked when she would join them in the dining area, she would reply, “I’ve had mine in the kitchen.” [4]

The family focus extended to relatives and friends and thence to the community at large. It overcame innate prejudices in the face of need; need for help, for recreation and for entertainment. The few pubs, the various organisations, such as lodges, societies and sporting clubs, together with Mechanics’ Institutes and Temperance Halls provided areas of common interest and cemented the feeling of oneness that permeated the community.

For much of the time, travel for any distance was laborious and uncomfortable. For instance, May Keeley recalls a train fare of one and seven pence ha’penny, second return, for the journey to the City and back. If you had to wait for the hour between trains, the Waiting Room had a cosy fire in Winter. The railway porter provided chopped wood. The trains on the Frankston line were electrified in 1922. [5]

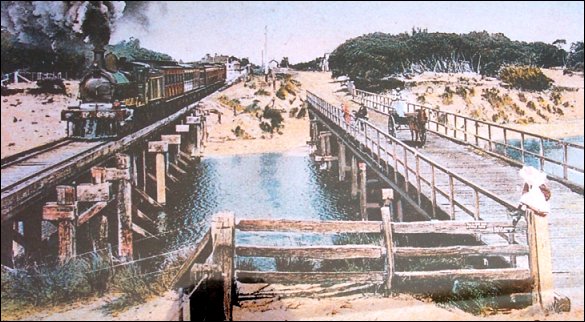

Stream Train crossing Patterson River c1905. Courtesy Chelsea & District Historical Society.

Many who lived through the first quarter of the 20th century had experienced the ‘terror of 1893’ as the financial crash of that time has been described. The memory, and consequences, of many banks and building societies closing their doors was not something to be forgotten. Lifesavings disappeared, in many cases never to be replaced. In the main, for much of the time, the smaller centres did not have local banking facilities.

There was other evidence of the effects of relative isolation. News travelled comparatively slowly when contrasted to the facilities we take for granted today. It is doubtful if the news of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 impacted on this hard working, striving to survive, community. Even the Police Strike in October 1923 (resulting in the dismissal of 627 policemen and the appointment of special constables) would not have had the publicity, or discussion, which would be accorded a similar incident today.

World War I and its consequences necessarily impinged on the nature of the community spirit that characterised this lightly populated district. Curiously, most of the people interviewed did not remember their parents or grandparents discussing those days other than on ceremonial occasions such as Anzac Day. They believed that RSL clubrooms were centres for mateship and reminiscence.

Frank McGuire has recorded a specific, but characteristic, instance of the spirit of the times. Dudley Tregent had been blinded by a mortar shell near the end of the War, and the people of Carrum rallied around to collect the large sum of money needed to enable him to further his studies, using the braille method. He became one of Melbourne’s most respected barristers and for many years was Honorary Legal Adviser to Legacy. [6]

Six O'Clock Closing, introduced in 1916, would have had a variety of consequences, including the development of sly-grog and licence difficulties for publicans. A certain hotel, in Carrum, came close to losing its licence, but overcame the problem by changing the name on the licence! Alf Priestly learnt that his father chose to leave the Mallee for Carrum at least in part because Alf's grandfather, who owned the Riviera Hotel, “had been a naughty boy with the licence a couple of times and there was only one more strike and he would lose it.” Alf notes that, earlier, “Pubs were controlled by 21 miles from Melbourne. That’s why the Riviera became able to be opened on Sundays, because you were outside the inner-Melbourne zone.” [7] The introduction of the controversial six o'clock closing legislation may well have been a factor in the District's community spirit, because the public and private bars were centres of social exchange.

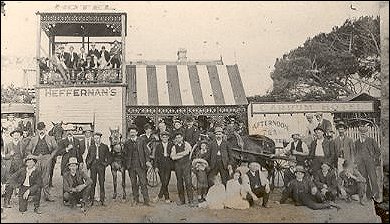

The Carrum Hotel and the site of the Riviera Hotel. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society.

Bob Robertson recalled that, “for most, it was a developmental or subsistence era. There were many instances of people who, for varying periods, actually had no money at all. There arose, in consequence of the absence of cash, various forms of barter. My eggs for your cauliflowers, your maize for my milk, for instance.” The product of necessity, the solution by ingenuity, these transactions were best arranged by equals among equals. There was no embarrassment, it was simply commonsense. There existed a special camaraderie, born of multiple contributing influences, that is characterised by the essentially Australian word, mateship.[8]

The emphasis must necessarily have been on the local and the immediate. Most of those living in the District derived a hard-earned pittance from the labour of their hands. Dairy farmers “sat under the cows” as Bob Robertson remembers very well, “twice a day and seven days a week.” [9] Market gardeners, in the process of developing their holdings, continued working outdoors while there was light. Transport was laborious and difficult. At times the markets were precarious and impossible to predict. It is not surprising that, through a period which saw the end of Queen Victoria’s 64 year reign, the reactionary period from 1901 to 1910 when Edward VII held sway and the time of the sailor King, George V, extending, as it did from 1910 to 1936, royalty was given little time or thought. No doubt, the schools paid attention to the niceties of ritualistically saluting the flag but as Bob Robertson remembers, “At school you were looking forward to milking cows. There were smart kids among them, you know. But the majority of them were dying to get home on the land ... everybody was milking cows. They were dying to be fourteen. Turn fourteen you were right.” [10]

For the people who were literally slaving, the men on the land and the women in the kitchen, devoting their lives to their families, incidents like Federation, celebrated on 1st January 1901, must have seemed far off and of little immediate significance. Similarly, the introduction of the Basic Wage, largely in consequence of the famous Harvester Judgement of Mr Justice Higgins in 1907, may not have seemed of great importance to those whose growing sons provided substantial parts of their labour requirements. The team spirit, the emphasis on the local, flourished because of the immediacy of wresting a living, in what were frequently most unfavourable conditions.

Self reliance and a sense of responsibility were major components of the community spirit of those days. For much of the time, for example, medical services were limited and hospital facilities were slow to improve. Some of the procedures were primitive. Bob Wright, born in 1917, remembers very clearly, long before the Chelsea Hospital, when he was a young lad, having his tonsils out on the kitchen table. “One of the doctors held the chloroform bottle over the head and the other one pulled the tonsils out. Just on the kitchen table.” [11]

He also believes there was a lot more excitement in those days than there is today. “Only because small achievements were great events. And I feel that even to be able to buy a new machine one year was a great achievement whereas today they put it on Bankcard. But, in those days, it was buying what you could pay for and, also, being paid for what you did.” There was also a growing pride in being Australian. Perhaps a bias. Bob remembers reading a book by an English migrant who came to Australia soon after World War I and was met on the wharf by the same prejudice that Unionists displayed, say, in the 1960’s. “Yes,” Bob says, “It did exist. He was a Pom! Considered to be worse than the Asians.” [12]

A major ingredient in the development of a vibrant spirit in the community was the individual, often scarcely publicised, contributions in cash, kind and services by some residents of the District. Speaking of his grandmother, Don Smibert recalls something of her activities in Mordialloc. “She was into a lot of things in the community. For instance, she was a ‘Guardian of the Foreshore’. I don’t know when she began, but the badge I have is dated 1920. And, my grandfather, Daddie Jim as we called him, took it upon himself to build things around the area like swings and seats and that kind of thing. He just did it off his own bat.” [13]

Swing built by James Evans in Attenborough Park. His daughter Clare (Mrs Smibert) is seated on the swing with four nieces of Hugh Brown on the right. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society

Another example of selfless dedication to the common weal was Bob Wright’s father. He was a Life Member of Chelsea, Carrum, Edithvale, Mordialloc and Mentone life saving clubs, and a Vice-president of the Royal Life Saving Society of London. Endless hours were devoted to training and examining lifesavers and to raising the funds for the development of this vital service. Bob recalls the annual dances and his mother boiling coffee in a bag at home to make the basis of two big copper-fulls of coffee with milk. “That was where people got to meet each other,” he adds, nostalgically. [14]

The characteristics of independence, fortitude and determination were common to the times and the community. The establishment of the Gartside Canning Factory in Centre Dandenong Road, Dingley in 1916 was an example. Henry Jonathon Gartside and his four brothers developed a thriving enterprise as a result of adverse conditions in their market gardens. [15]

Ken Smith has good memories of Holly Rose and Glad Rose of the family of undertakers who “spent a lot of money on looking after people. Quietly. You didn't know about it ... and their house ... the front door was always open” [16] This was taken for granted. As Jean Mitchell remarks, “People usually helped each other.” [17]

Glad Rose with Citizenship Award for Community Service. From the Leader Collection.

Asked how she would assess the community spirit of those times, May Keeley says, enthusiastically, “Oh, very good. Yes ... For example ... say my Mother got sick, the neighbour would come along and do some work, clean the house ... another would come along and do some cooking. You’d go and see people and help them as much as you could.” She quotes an example, giving credit where it is due, of “a woman round our way, you know, she knew all the gossip and everything, and all like that. She’d make mountains out of molehills and so forth, but she would be the first there to help you if you were sick.” Asked if this was characteristic of people generally, she smiles. “Well, as for helping she was characteristic, but she’d only be one-off the way she used to talk!” [18]

The practice of self-help and mutual support was, in fact, a major element in the spirit of the community. As Bob Robertson puts it, “Somebody would be around. We had a lot of going around and helping people ... trying to help them.” [19] Alf Priestly has similar memories about sources of help in time of need. “I think it came from the neighbours and the general community. Facilities were not available in those days as they are now and having to do with childbirth and babies ... I think there were two women who were classed as midwives in Chelsea. One lived in York Street and one who finished up being a neighbour of ours. There was only one doctor in Chelsea and eventually a practice was started in Edithvale but the nearest, then, was Mordialloc. No doctor at Carrum, so the nursing midwife was a great help to a lot of people, but the people helped one another.”[20]

In an era and a district where most were engaged in a desperate struggle to survive and where transport, communication and the infrastructure generally were primitive and inadequate the people triumphed. Based on unremitting self-help and mutual support, theirs is a proud legacy.

Footnotes