Noble

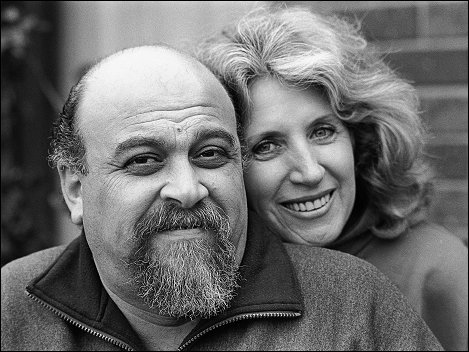

Photograph, Kris Reichl.

I came to Australia in 1969 from Cairo. I was 19 and I came by myself, not knowing anyone.

My family were very upset when I told them I wanted to leave Egypt. I was the first person on either side of the family who had migrated and they didn’t understand. But I have always known my own mind.

I wanted to leave Egypt because I was unable to work as an engineer. I finished my engineering diploma in 1968 but I couldn’t get a job until I completed national service. At the time I knew I could be in the army for an indefinite period because Egypt was on war alert. I didn’t want to waste all that I had learnt.

I applied to go to the United States, Canada, Brazil and Australia. Australia was really the last place I chose because I didn’t know anything about it. When I went to the Australian Embassy in Cairo, they had three photographs: a kangaroo, a koala and the Melbourne Cup. I looked through history books and found that Australia was a place where England had dumped all its crooks and thieves and I thought it would be rough and ready like the American Wild West.

I asked older people in Egypt about Australia and they told me not to migrate there because the men in Australia were huge. During the war, Australian soldiers seemed enormous and some of their drinking habits had left a bad impression.

Of course the Australian visa came first and I did not want to wait to hear from the United States, Canada or Brazil. Fifteen days after I received my Australian papers I landed in Sydney.

The food served on the aeroplane was completely new to me. As we flew over Sydney I looked down on house rooftops and thought we were landing in an army camp because in Egypt people live in large apartment buildings, not detached gable-roofed houses. I was very nervous. The aircraft flew in very low and I thought we were going to crash into the water. What a start!

I grew up in Egypt speaking French, Italian and Arabic. I soon realised that the English I had learnt at school was inadequate. The English I heard at the airport, with all the Australian slang, was a language I had never heard before. I couldn’t understand a word that was said to me, especially by the taxi driver. Today, many taxi drivers are migrants but the one I took from the airport was a fair dinkum Aussie and I didn’t know what had hit me.

I handed the taxi driver a notebook full of addresses that people in Egypt had given me. The driver picked the closest address and drove me there.

In the 1970s there were very few Egyptians in Australia and if I heard someone speaking Arabic on the street I would cross the road and introduce myself.

My first impression of Melbourne when I moved here in 1970 was of a very grey place. It seemed quiet and without friendliness or warmth. I didn’t see a soul on the streets after six o’clock and found that depressing. But I met my wife Cheryl soon after I arrived in Melbourne and I decided to stay.

I started work in Australia in blue collar jobs and gradually worked my way up. When I sat in an office for the first time I stuck out like a sore thumb; the only coloured person among all these Aussies. But people were very helpful and I worked my way into management.

I started working at Nissan in 1977 and stayed there until the factory closed in 1992. You could see all the waves of migration represented in that factory. We had workers from 63 different nations and I suggested that we paint the factory wall with a flag for each nationality. Of course, we had fun and games because some nationalities had conflicts back home and didn’t want their flag placed next to certain other countries.

After Nissan closed, I got a job as operations manager for Chirnside Park Shopping Centre. I worked there for about 11 months until I was driving home from work late one night and had a head on collision with a stolen car, which left me disabled. I was in the Alfred Hospital for three months and then in rehabilitation for three years. Before the accident I had been a very active person but then my life took a completely different turn.

After my accident Cheryl and I found it difficult to access information about transport accident issues. Because of this experience we thought others must be having the same problems and set up the Victorian Road Accident Support Association where members help each other by exchanging information and experiences.

I am also a committee member of the Senior Citizens Social Club for the elders of the Coptic Orthodox Church in Oakleigh. We realised that many older people stayed at home all day and depended on their children to go anywhere. Sometimes, their only outing was to the church on Sunday. Many of them couldn’t even watch television because it was in English. Members of the social club go on weekly outings and hear guest speakers. It is something for people to look forward to.

We moved to Clarinda in 1978 when it was a new estate. We were all young and we have grown up and changed together. Clarinda has always been a mixed area and, with the different waves of migration, you can see the changes in the shops.

When we first moved here most of the milk bars, delicatessens and bakeries were owned by Greeks and the green grocers by Italians. Now we have Asian green grocers selling different types of vegetables and some of the bakeries are run by Vietnamese and Cambodian people. You can see the French influence in their cakes and breads.

I am happy in Clarinda because many people around here know me. We are not in and out of each other’s houses but we look out for each other.