The Methodist Homes for Children: The Beginning

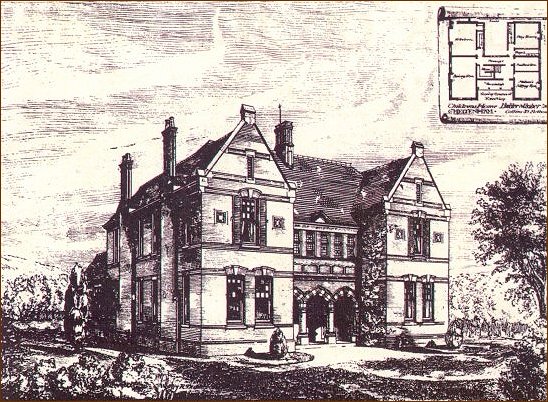

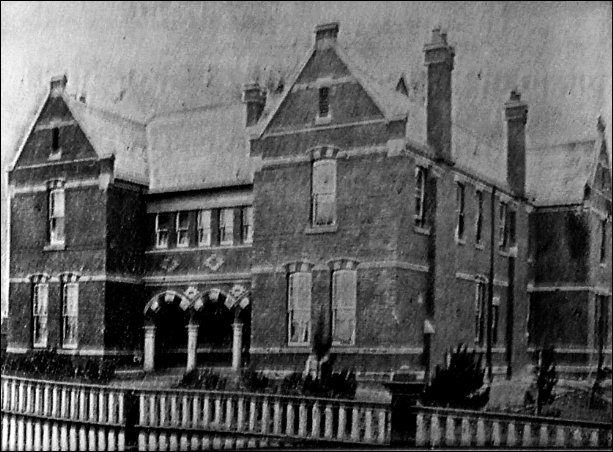

Architect’s sketch of proposed Methodist Homes for Children at Cheltenham, c1890.

To help understand the reason for the establishment of Methodist Homes for Children at Cheltenham we need to look at the last half of the nineteenth century, to see the prosperity that occurred following the discovery of gold, and the effects of the bust, booms and strikes that followed in the eighties and nineties.

The news of the discovery of gold in 1851 took Australia by storm. Thousands of settlers left their jobs to head for the diggings. Immigrants from all over the world flocked in. The free immigrants in the first two years exceeded the total number of convicts transported to Australia in all the years of transportation. From 1851 to 1861 the population trebled. In Victoria the 80,000 population became 500,000.

The social, political and economic outlook in Australia changed, Victoria most of all. A building boom saw major commercial, educational and cultural buildings being constructed. Increases were seen also in agricultural and secondary industries. Transport was improved with Cobb & Co. coaches, river transport for the wool bales along the Murray River, and new railways and wharves were built to meet the demands of the newcomers.

With the gold boom petering out, many of the diggers turned to other pursuits. The natural resources of the country were developed, and primary and secondary industries blossomed. Mining developed; not only gold, but also coal, silver, copper and tin, all earned money for Australia. With the growth of the wool industry, by 1871, it had become the major export earner for Australia. The wheat industry developed, and with the invention of the stump-jump plough (which made it possible to cultivate soil from which ground level stumps and tree roots had not been removed) and the use of new strains of wheat more suitable for Australian conditions the industry prospered. Cattle farming and the sugar industry also developed at a great rate. Manufacturing industries were also stimulated by the rushes, especially in Victoria. So the years following the gold rushes were prosperous ones.

But the incredible boom was short-lived. The rushes had stretched all existing services, but with the dramatic increase in population (between 1880 and 1890 the increase in Victoria was 114,000) the demand on existing services was extreme.

The wealth generated by the gold rush saw speculation in land. Prices of real estate in Melbourne city were not reached again for another 50 years. New suburbs were built and the governments borrowed money from overseas to build railways and expand public works. Everyone was happy. They believed that the rural sector would keep growing and the future development of the big cities would continue

Disaster struck when overseas prices for wool fell dramatically. Early warning signs had been disregarded. With this, and the collapse of the housing market in 1890, the unprepared economy entered into what was to be the largest depression in Australia till that of the 1930s. Wool, wheat, and metal prices continued to fall, and consequently created a panic. Banks failed, overseas loans were withdrawn and unemployment was rampant. To make matters more difficult, in 1892 the worst drought in Australian history commenced and was to last for 10 years. Two thirds of the country’s live stock perished and farmers were forced off their land.

The depression also set the stage for industrial unrest. The trade unionists, loathe to relinquish the gains they had won in working conditions, set out to organize the Great Strike of 1890. Due to the lack of strike funds, and with the huge pool of unemployed, the strike failed. However, the unionists saw that the strike weapon was not powerful enough to achieve their goals- they needed to have a say in government so they threw their weight behind the small parties which eventually became the Australian Labour Party.

It is against this background that I believe we can trace the need for the establishment of a work for neglected children in Melbourne.

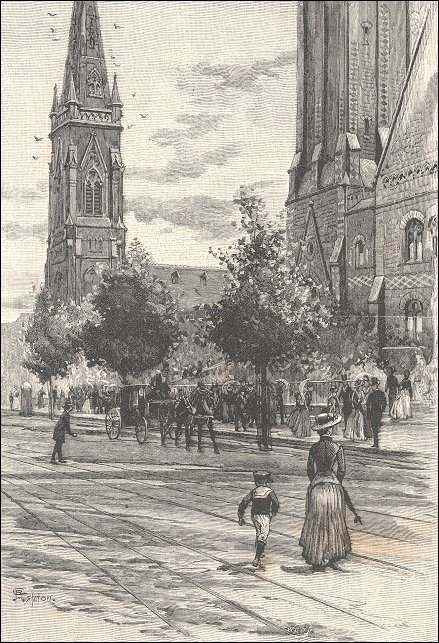

In 1858, Wesley Church, the huge bluestone Cathedral of Methodism, was opened in Lonsdale Street. The Church had moved from its original site in 1853 at the corner of Collins and Queen Streets. By the 1880s the Church was faced with the problem of a dwindling congregation as its members transferred to suburban congregations. While the Presbyterian and Congregational Churches had the same problem, they had the advantage of being located in the elegant area of Collins Street and also much nearer to Flinders Street, in reach of the Sunday commuters. In its position in Lonsdale Street, Wesley backed onto the notorious red light area of the city known as “Little Lon”. There had been critics of the position when the Church was built in 1858, and by the mid eighties the Church was marooned in the centre of Melbourne’s back slums, right in the centre of vice.

Presbyterian and Congregational Churches In Collins Street Melbourne, 1888.

In response to Wesley Church’s need, in 1884 the Home Mission Society appointed a Biblewoman. Along with the distribution of religious tracts and counselling, she would provide money for rent and food, clothing, advice on the city’s charities, and support for the sick and aged. By 1888 there were eight Biblewomen working in the city and the inner city churches. The need became greater and greater as the Biblewomen found that side by side with the progress of the city in material wealth and magnificence there is an increase of moral degradation and great physical suffering.

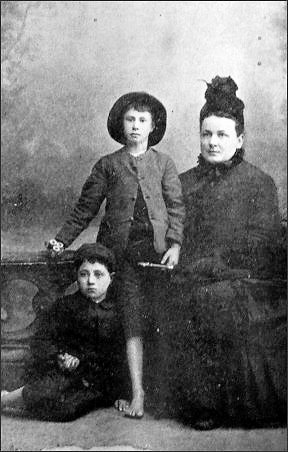

The first Biblewoman, Mrs. Varcoe often came into contact with numbers of neglected and outcast children of both sexes. In July a baby was left at her home, but because no trace could be found of the mother, the child was cared for and eventually was adopted by a country family. Not long after this, two small boys in a very pitiable condition were found roaming the streets. Mrs. Varcoe took them into her home, and reported this to the minister of Wesley Church, who saw the need to take a house to care for those waifs and strays who were rescued from the streets. This home became known as Livingstone House in Drummond Street Carlton. It became necessary to have the work authorized by the Government and Rev. J W Crisp of Wesley Church and Mrs. Varcoe were appointed to care for any children under sixteen years of age who were known to be in a house of ill repute and were committed into care by a magistrate. The Biblewomen found children living in conditions of moral danger with their mothers involved in prostitution; others were living in the ‘back slums’ area where there was an under class of adolescent boys, largely uneducated and surviving on the edge of a casual labour market as street hawkers. They went to one place where the father was “worse for wear due to drink; and there was no food for meals for the three children. Although the children had a great affection for their father, at their father’s request they went with the Biblewoman. A twelve year old boy was found wandering Lonsdale Street with his blind mother. The father had died; they had no friends, no place to sleep, and fourpence between them. The mother was placed in the Immigrant’s home. He went and was placed for ten years on a farm near Alexandra when he returned to Melbourne to work in the railways. A baby, Clara was so neglected that her drunken mother had let her fall into a fire where her foot was burnt off. She stayed at the home for four months where she died. Eve, an eleven year old, was found with her drunken father sleeping in a fowl shed, and living on scraps of bread which she picked up round the streets.

The First Two Boys at Livingstone House, Martin and Bob with Mrs Varcoe, c1887.

In a short time, the work grew to such an extent that the house next door was taken. It soon became obvious that other premises would be needed to carry on the work. When these stories were raised at Church meetings, there was a very good response, especially amongst the young people of the Church. They worked hard, holding bazaars, and selling cardboard bricks to raise funds for a new building

The question of site occupied many enquiries and delays, but eventually Cheltenham was chosen. The plan was not to build a barracks; but to take the children into a home, care for them for a few months and then transfer them to homes in the country. The Committee’s aim was that “It would not be an Institution-- it is a Home; Mr. Trudgeon is not the Master of it. -- He is the Father. Mrs.Trudgeon is not the Matron—- she is the Mother. Children were not to be ‘inmates- but family.” The Committee was concerned to ensure that the new Livingstone Home would have a homelike nature. Only in exceptional circumstances would children be allowed to stay in the Homes for a lengthy period. The Committee from experience concluded that the younger the children were when rescued the more likely the work of reform would be permanent.

Matron Trudgeon.

On 24th. November 1891 a large crowd gathered alongside the Point Nepean Road at Cheltenham to witness the opening of the new Livingstone Home. It was a two storey double-fronted brick building facing Point Nepean Road. The fourteen rooms could now accommodate twenty five children, more than double the number at the North Carlton House. (the name was transferred to the new building but changed to Livingstone Home. The Governor in Council approved the change of name also to the ‘Wesleyan Church Neglected Children’s Aid Society. The Home thus, became recognised by the Wesleyan Church and was seen as an outcome of city mission work, an example of practical charity and a new sphere of, usefulness that has before come within the range of, the organisation. Others saw it as the changing point in the Wesleyan Church’s history where it became a denomination rather than a sect.

The honour of opening the door went to Mrs. Hope Crisp who along with Mrs. Varcoe, had three years earlier, led the Wesleyan Church into the field of child rescue in opening the Home she said:-

May our Home now opened be the door through which many may be led to lives of, honour, virtue, and distinction on earth, and to life ever lasting in our Father’s home on high.

and then went on to share with her audience a poem which she believed epitomised the nature of, the work on which their church had so recently embarked.

Who’ll bid for the little children,

Body, and soul, and brain?

Who’ll bid for the children,

Young, and without a stain?

“I’ll bid” said Beggar, howling.

“I’ll buy them up one and all.

I’ll teach them a thousand lessons,

To lie, and skulk, and crawl.”

“and I’ll bid higher and higher”

cried Crime, with a wolfish grin;

“I love to lead the children

In the pleasant ways of sin.

They shall swarm the streets to pilfer,

They shall plague the broad highway,

Till they grow too old for pity,

And ripe for the law to stay

“O Sham,” cried True Religion

“O Shame! That this should be

I’ll take the little children,

I’ll take them all to Thee;

I’ll raise them up with kindness.

From the mire where they have trod,

I’ll teach them words of blessing,

I’ll lead them up to God”

Spectator December 4, 1891

The Building Fund had very few donations above ten pounds but most were of a guinea. However, the Committee tapped a new source of funds, that of Sunday School children. They were attracted to the cause, they filled cards by putting a pinprick in a square for each penny collected; held concerts and bazaars, raising five hundred pounds and paid for the furniture in the homes. Very little of the cost of £2500 remained on Opening Day.

On Scholars’ Day, a week following the Official Opening, two thousand Sabbath Day Scholars and their families came by special train to celebrate and enjoy the General Post Office Band, games and a picnic.

Even though the Committee had the desire to stress the home-like nature of Livingstone Home, it could not escape the institutional atmosphere. The four bedrooms had five beds and one cot in each. The transient nature of the children and the splitting of families that could not be placed together meant that Livingstone Home, while not a barracks was more institutional than was admitted. The need to keep children in a ‘receiving home’ atmosphere over an extended period whilst waiting for a placement in the end forced an institutional model on most of the voluntary child-saving societies. Livingstone Home was an anti-institutional institution

In the summer of 1897 because the scarcity of water was so great, and the cost of purchasing it was so high, it was decided to sink a well.

A typhoid epidemic in 1898 resulted in two deaths, one a boy aged nine, and the other, Kate Brinton, who had cared for many of the children with typhoid, who contracted the disease and died. This was the only epidemic disease to claim lives in the Homes. Although living together meant that the children were particularly prone to infectious disease, with the observance of quarantine periods and other precautions, by comparison with the general community, deaths in the Home were few, and mostly the result of longstanding illness.

Children still came to the Home to be cared for. One family of five, aged thirteen to two, were left in a van waiting for their father’s return. When they were unable to find him, they were sent to the Home. Also, two motherless children, beaten and ill-treated by a drunken father; and a Chinese girl, whose mother was found dying in great poverty in a Chinese camp, came under the Home’s care. A motherless girl, rendered so by her father, who killed his wife, came to the Home and was adopted by a country family. Three motherless children were neglected by a drunken father. The elder girl did what she could to care for them, but as her eight year old sister was deaf and dumb, she could not do much. There were cases of need where parents were hardworking, but due to sickness were unable to care for the children. One father wrote to “thank the Home that you would be so Christian like to extend such a welcome to my children.”

Children who were sent out to the country were visited regularly by local ministers and friends of the committee and satisfactory reports were received of their progress.

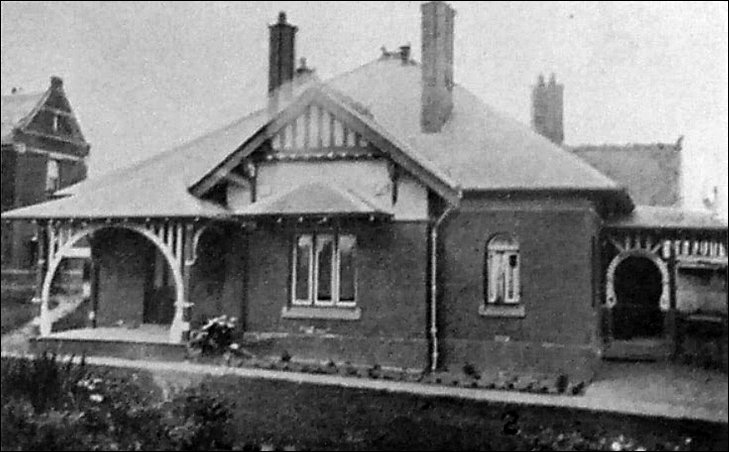

A donation of £150 from an Estate has been earmarked for a building to be placed on the piece of land that had been purchased by Mr. Eggleston. However, the principle of ‘no debt’ meant that nothing was to be undertaken until the building was able to be paid for ‘in full’. Eventually on October 25, 1902 the foundation stone for the Queen Victoria Cottage was laid by Mr. Eggleston. Many interested friends were present, and attended again on December 12, 1903 when the Cottage was officially opened by the Rev. E. S. Bickford. The building with its new laundry was furnished by the efforts made once again by the Sabbath School Children across the State.

Queen Victoria Cottage. Courtesy Uniting Church Archives.

In November 1905, the Premier and Chief Secretary of Victoria made an unexpected visit to the Livingstone Home. Hansard reports:—

The Home was conducted without any Government Subsidy. The whole of the buildings, which were in good order, were fully paid for, and there was not a single penny of debt in connection with the maintenance. The Institution was maintained by children attending the Sunday Schools attached to the Methodist denomination. They not only maintained it in connection with new buildings, but also provided the expenses of maintenance. Some 400 children had been brought up in it, as to every one of whom it was asserted that the management knew what had become of them, and not one of them had not turned out well. He granted that all the private institutions were not so successful.

They were kept at the Home till their education was completed. They were educated at the State School which was close by. The average attendance at the Institution was close to sixty, and at present there were twenty children there under two years of age. He was delighted with the place. It was almost a palace. One could almost eat off every part of the floors. A new building had been erected quite recently to keep the younger children separate from the older ones. This showed that it was not fair to condemn all these private institutions.

Livingstone House.