Methodist Children Homes: The Post First World War Years

The Bickford Wing officially opened by George Swinburne, December 12, 1908.

Six hundred and thirty nine children came to the Methodist Children Homes at Cheltenham in the period 1917-1929, and most of them were able to be placed with families. However by 1920 the committee began to see that the rescue element of their work was disappearing. Many families were in need of temporary relief because of illness, unemployment or family breakdown. One went home after two weeks; another couple after two years of care. Emily, a former Homes resident, was placed in the country, married a young farmer, who died after five years leaving her destitute with two young daughters. She looked to the Homes for help but she refused to sign their transfer, as she wanted to provide a home for them again, even though it took her seven years to achieve this.

Less than eight percent of admissions during this period were of children removed from unfit parents; usually due to neglect rather than abuse. They stayed till old enough to work, and many found their relatives and returned to live with them. Nine percent of admissions were committed for behaviour problems but few of them stayed for any length of time. The Homes offered asylum but could not keep individuals against their will. When the demand for admission increased in the depression years the practice of accepting children in need of reformation came to an end.

These years also saw the last of the illegitimate children being admitted. The Committee were unwilling to accept children under twelve months. They would admit the child but the Committee would arrange for a nurse only if the mother would sign a transfer of guardianship and pay the full costs of care till an adoption could be arranged. This caused some concern amongst some groups within the Church and from them there arose the ‘cry of the infants’. In 1924 The Young Men’s Methodist Movement approached the committee about the practice. Dr. Douglas Thomas, Arthur Wilson, and F. Oswald Barnett (who had made an exposé on the slums of Melbourne) met with the Home’s Committee and challenged the Committee to get back to the Committee’s original ideas. This made them feel uncomfortable especially in the light of the recent death of seven toddlers. When the young men said they were prepared to have a fund raising effort, the ladies suggested that a modern babies home be built at Cheltenham. This was rejected on the advice of the Young Men’s Methodist Movement doctor, and a site was chosen in South Yarra, on the banks of the river. Through their formidable fund raising abilities, they were able to construct a modern and scientific institution. The Methodist Babies Home was opened in December 1929. This reduced the pressure at Cheltenham to provide for young babies.

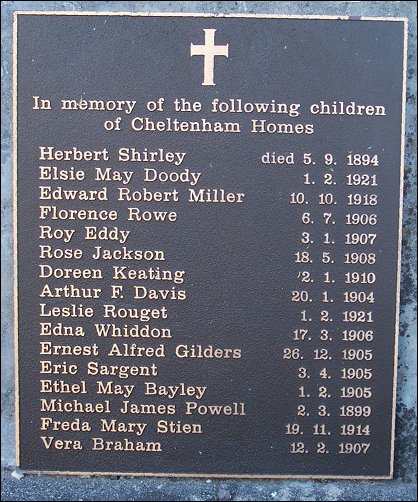

Plaque on the grave of children from the Homes at Cheltenham Cemetery, 2003.

In ordinary times, the opening of a new institution specifically for babies might have been expected to relieve some of the demand for admission to the Methodist Homes, but the opening coincided with the onset of the Depression which placed the Homes under even greater pressure. The spread of unemployment led many single fathers to give up the struggle to support their children. Later, married couples did the same. In March 1929 the Committee tried to get parents of temporary children to remove them if they could but few obliged. In the next six years, there were few vacancies as not many children were able to be placed. In 1932 only three children were admitted. Those admitted were staying longer with fifty percent staying at least fifteen months and eight percent longer than ten years. The destitution of the time led the Committee to turn away from child rescue to offering a home to children who had nowhere else to go. They sheltered many children who had lost one or other parent through death or others whose families had crumbled around them. Children from large families were thrown into poverty through sickness and unemployment. The Homes also provided shelter to several children whose health had been undermined by want and disease. Some parents were too poor to provide the children with the nourishing food they needed to recover.

The Depression made a lasting impact on Victoria’s child welfare By 1935 seventy homes accommodated 20,760 children four percent of Victoria’s child population. In 1938 the Methodist Homes varied little from the overall profile of the other homes. With eighty three children it was the seventh largest institution, half the size of the largest home, the Broadmeadows Foundling Home.

Queen Victoria Cottage, foundation stone laid October 25, 1902.

The Second World War produced dramatic changes. Increased affluence removed the mass poverty which had in the past forced many parents to surrender their children. However the increasing social dislocation made up the shortfall to some extent. In 1940 to 1951 three hundred and four children were admitted, an average of less than twenty four compared with forty seven in the pre-depression era. Most stayed longer in care.

The outbreak of war in Europe suggested another possible source of children for the Homes. As children in London and other major English cities were evacuated, a scheme was floated to bring children with few family connections to safety in the dominions, but with the loss of a ship on the way to Canada brought an end to those plans.

After the victory, the idea was revived. The war had left the institutions in England crowded with children while similar homes in Australia had many vacancies. The Commonwealth Government in introducing the mass migration scheme offered to help with a child migration scheme. This offer of financial assistance appealed to the Homes, which needed money to embark on a rebuilding scheme, so they offered to provide long term placements for fifty children. Unfortunately, the scheme did not take off. The recovery in England after the war occurred more quickly than had been expected, and with a more hopeful future there were not enough child migrants to go around. Available European children were offered, but the Committee was hesitant. Eight refugee children who were from Bonegilla Migrant Centre were accepted in 1949-50 but they only stayed long enough for their parents to earn enough to establish themselves and to be able to resume their care.

A visit to Australia of the Rev J H Litten of the Methodist National Children’s Homes in 1948 seemed more hopeful. His concern was mainly for young people, but eventually he agreed to the suggestion that twenty five individuals would be sent, amongst whom would be a number of children. The youngest in the first group of twenty five was nine and most were well into secondary school. A group of teenage girls was to go to Perth, but when the arrangement fell through, they were accepted by the Homes and Cato Cottage was used as the hostel for these new arrivals. There were problems; the sea voyage had given them a greater freedom than they had in England, and many found it hard to adjust to the Australian educational syllabus. In all thirty seven children came to the Homes the youngest being six. Of the twenty primary school age children, only sixteen spent less than two years in the Homes. The hope for long term placements through the scheme did not eventuate.

Amongst the changes during the war, the Committee found that destitution was no longer an adequate measure of need. Increasingly, the Home became a haven for the child victims of desertion and divorce. The Committee said, “The war was having an upsetting influence on society encouraging a laxity in regard to marital obligations” and the Homes were being called upon to pick up the pieces. Although unemployment almost disappeared as a cause for admission, illness continued to cause disruption in working class families. With treatment a possibility, tuberculosis victims were confined for long periods in one of the many sanatoria around Melbourne, which caused problems for families seeking emergency child care. One family of eight had both parents in a sanatorium. It was two years before the mother was sufficiently well enough for them to return home.

In 1938 the Children’s Welfare Department was finding their receiving depot overcrowded, and the supply of boarding out homes drying up. In order to help the situation, the Department was forced to approach all of the children’s institutions begging them to accept some of its children. As most of the income of the institutions had been depleted during the Depression, the offer of a regular source of income was quickly accepted. So in 1939, 2000 of the 3800 state wards were place in one of the seventy institutions which had joined the scheme. The Methodist Homes made a commitment that on request, and if vacancies permitted wards would be accepted. In the period 1940-51 almost fifteen percent of the children in the Homes were under the guardianship of the State.