Methodist Homes for Children: Education and Success

The First Grade at Cheltenham State School in 1917 included some children from the Homes.

The children at the Cheltenham Methodist Homes had little opportunity to learn by seeing, as they seldom left the property. The founders of the Homes had envisaged them as part of the local community but soon a combination of factors closed the Homes in upon themselves. The new families coming into the area in the early years were seeking a healthier and more respectable environment for their children, and were reluctant for them to share their education with the Homes children. In 1911 the school Committee moved for their exclusion. The Homes Committee rallied support, and at a meeting 60 of the 68 people rejected this suggestion.

In 1915 the local parents approached the district Medical Officer, Dr. Scantlebury, to recommend the children be removed because of the health risk. This placed the doctor in a difficult position. He knew the threat that infectious diseases made to the community, but as honorary medical officer for the Homes he had a loyalty to the children. Whenever one child in the Homes was suffering from a notifiable disease all the children had to be kept home. He made the suggestion that the Homes should have their own school, but the Committee felt that 1915 war time precluded a major fund raising drive. In October 1917 an outbreak of mumps with four months quarantine later, brought the issue to a head. The Education Department agreed to a school being held at the Homes, and the money for the schoolroom came from the estate of John Livingstone an old boy of the Homes who had done well, but was killed in the war. He left his whole estate to the Homes. Just after this, the Education Department withdrew their support. This was reversed in 1919 when the influenza epidemic quarantined the children for a period four months. Then the flu stuck the Homes, which meant a further five months break. For a time in September classes were held in parts of the Homes but in July 1920 the children and their teachers entered their own school.

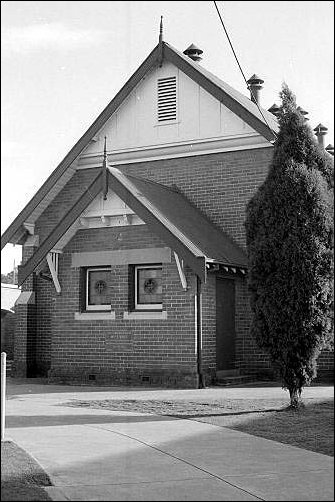

School Building at the Homes.

The internal school helped provide a continuity of education, but confined the children to a system which reinforced the institutional regime. In 1925, the Danks family gave a gift which helped provide a School of Domestic Economy to prepare the girls for their future as domestic servants. It was not till 1931 that children were able to move beyond the Homes school. First by correspondence, then in 1936, with attendance at local high schools, some children were at least able to have a choice of occupation in adulthood. Some then were able to take up apprenticeships or go to office positions or go to a commercial college course. n 1947 a gift of $5000 allowed for the payment of school, university or apprenticeship fees or for music and cultural subjects. Once the internal school was in operation, church became the only contact the children had with the outside world, but even here they sometimes met with rejection. Religion played an important part in life at Cheltenham. As a Methodist institution staffed by committed Christians, the Homes aimed to introduce the children to the Christian faith. Prayer and Bible reading were part of the daily routine. The Committee turned to the local Cheltenham Church to give the children an understanding of belonging to the wider church family. The children marched to church for the morning service, returning again in the afternoon for Sunday School, and the older boys were encouraged to go to the evening service as well.

Methodist Church in Charman Road, Cheltenham, 1977. Courtesy Leader Collection.

They did not always find themselves welcome. They filled the church by sheer numbers, but by the depression years their presence was increasingly resented. The trustees complained, “The Sunday School was overcrowded. The Homes children were admitted free to all activities, did not bring a collection, and usually took more than their fair share of the end of the year prizes. The children were a polluting influence on other scholars by discussing gambling and the like, but none of the sisters offered to teach in the Sunday School and help keep them in control.” Although usually such letters could be answered satisfactorily, the tension seemed to be seldom far below the surface. As the improvement in the economy occurred the children and the Committee were able to make a financial contribution to the church life. The trustees felt they were being asked to carry an unfair burden. In the periods of quarantine in the Homes, the children and staff were relieved when they could worship without the sense of being objects of charity,

Even if the children did not go out into the community, the community increasingly came into them. 1927 saw the commencement of a physical culture class for all school age children. Tennis courts, basketball courts, sand pits, and supervised playgrounds were provided for the children, and scouting and guiding were introduced. Also, Cato boys were allowed to go as paying customers to a regular gymnasium class at the Cheltenham Methodist Church. Not all of these groups were successful. Outside leaders found the children difficult and unresponsive, at least partially, because all activities were compulsory, and they tended to lose their interest.

For the children at Cheltenham who had known no other life, the old institution was “Home”. Matron Ross saw it as “Like one big happy family” and although many of the children may not have shared her enthusiasm, for most of them, the Homes became their family. Some did not do so well working on farms; others settled down and were successful in eventually owning their own farms. The Committee, through local church committees and ministers, kept a check on their placements - some were successful, some were ill treated and returned to the Homes; some absconded and fell foul of the law. Some settled into family life; others not so. Some of these went to live in Wesley Mission hostels. For many who had spent a large part of their lives in the Homes it was a wrench to move out into the world. Losing their home and their family often made them feel alone.

However, the committee was proud of its successes. One boy graduated as an accountant and worked in the Attorney General’s Department in Canberra. Several girls completed business college courses and obtained good positions in offices. Other girls became nurses, and at least three boys were ordained as Methodist ministers; many became successful farmers. One girl went to work in African Missions. The old boys and girls decided themselves to gather together as a group which they called the Living Stones Union. In 1939 the group circulated news of others who had passed through the Homes. For many the L S U provided the family they otherwise lacked. It had a message of hope; an institutional childhood was not an automatic recipe for disaster. The regular stories of happy marriages and growing families counteracted the popular psychology that without proper parenting you could not be a parent yourself. No one was pretending that it was easy to go out alone into the world but the Children on the Methodist Homes for Children were at least given a sense that they had something to offer.