Prisoner of War

On Sunday September 9, 1939,the Prime Minister of Australia, Robert Menzies announced Australia’s intention to join Great Britain in fighting Hitler’s Third Reich. "It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war on her and that as a result, Australia is also at war." It was less than two months later, on November 24, 1939 that Ronald Walter Lister with several friends went to the Australian Army Service Corps Depot in South Melbourne and enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces (A.I.F.).

Ron Lister as a senior cadet in Ordnance Militia prior to World War II.

This was not Ron Lister’s first contact with military service, as at sixteen years of age he joined the Ordnance Militia, the service that was responsible for managing and providing the stores for fighting units. He joined as a senior cadet and was soon equipped with his uniform which included a navy blue jacket with red piping on cuffs collar and epaulettes and large brass buttons. The trousers were navy blue with two red stripes on each leg and fitted with buttons for braces, no tags for belts. But it wasn’t just the uniform that attracted Ron to serve. There were several reasons, including a family tradition. His father had been in Egypt and France as a company quarter master sergeant and continued in the army until 1920. Two brothers of his mother had also fought in France in the Great War and a cousin of his mother had served in both the Boer War and World War One.

Born in Richmond Ron, when eight years old, moved with his family to Mentone. There he attended Mentone Primary School and Mordialloc High School where he completed year ten in 1933. At the time the Great Depression was still affecting the Australian community. As Ron explained, "You took any job offering. I was happy to get a job with Sheridan the chemist in Mentone, as a messenger, but realized there was no prospect of becoming a chemist owing to the cost and time involved in qualifying. Shortly after I joined a friend in the city and became an apprentice process engraver. It was a dirty job working with nitric acid and printing inks. I was working there when war broke out." (Whitehead, 1998)

On January 11,1940, Ron was aboard the first ship to leave Melbourne for Palestine, the Empress of Japan. "Imagine my surprise when I finished in a single-berth First Class cabin all to myself with a Chinese steward to wake me up at 0700 with a cup of tea and a biscuit. … I had to wait 6 years to eat in luxury like that again." (Lister, 1993:15) It was in February 1940 that rumours of a big operation began to circulate and it was at the end of that month that Ron Lister, now a First Lieutenant, moved out with his section to Greece via Cairo.

The Empress of Japan in Melbourne prior to leaving for the Middle East.

The German invasion of Greece began in April. Australian, New Zealand, British and Greece troops raced north to meet the invading force. The resulting actions were hard and difficult, often with heavy casualties. The troops were cold, hungry, physically and mentally exhausted by constant effort and danger as they fought rear guard actions. On 22 April General Blamey gave instructions for the withdrawal of all units to various evacuation ports with embarkation starting two days later.

"Soon the signs of hurried flight began to show up with increasing frequency; where troops had bivouacked the ground was smothered under a carpet of rejects from a retreating army, clothing, blankets, mess gear, broken down vehicles and above all paper, it was everywhere; nothing appeared to have been burnt just left to be collected by the local Greeks or salvaged by the enemy. … Some engineers from Melbourne did most of the damage, blowing bridges over sheer drops into gorges, bringing down whole sections of roads on steep mountainsides, with the final touch of loading railway trucks with explosives and time fuses and sending them on their way into the numerous railway tunnels on the Braillos Pass itself. …enough time had been gained to allow the main body of troops to get away by ship and the demolitions held back for three days any advance by German vehicles." (Lister, 1993:39)

Photograph in Greece of Ron Lister to be included in identification papers.

Ron and his unit left Greece on board the HMS Glen Earn, an infantry landing ship, formerly a passenger vessel on the South African run and put ashore in Crete. "The only British troops on Crete when we arrived consisted of a small Royal Engineers unit … and a Dock Operating Company of Royal Marines, no reserves of supplies or food on hand, no tents, blankets, clothing etc .. and here had arrived twenty thousand plus troops, dirty with worn clothes and boots, half of them not being in possession of weapons, tired, bomb-happy…" (Lister, 1993:14)

The Germans invaded Crete on May 20, 1941 using parachutists and glider borne troops. They attacked several locations where they were met with fierce opposition by Australian, New Zealand, British and Greek troops, many of whom were poorly equipped after their evacuation from Greece. By May 31 the Germans had gained the upper hand and the order was given to capitulate.

"This was the beginning of four years as a guest of Nazi Germany," said Ron. "We were tired and distressed. We had been on the run for several days with everything very disorganised. Military police who normally control traffic were not in evidence. There was no food and little water in an arid and mountainous area. The Germans didn’t have much food and what they had came from our dumps.

"One of the first things the Germans did was to separate the officers from other troops. The officers, who could not be put to work under the Geneva Convention that laid down conditions governing the treatment of prisoners of war, were transported by plane to Athens. There we were paraded through the streets of Athens to expressions of sorrow from the local population and dropped off at a railway siding south of Athens. Boarding Orient Express type carriages with a piece of raw fish and a couple of thick biscuits, we travelled to Gravia where we detrained to march forty miles over the Braillos Pass before reboarding a train. The food was to last us for five days.

"Arriving at Salonika we were incarcerated in a derelict Greek Army barracks. The plaster was peeling off the walls and the place was lousy with rats, fleas, lice and any other bugs you care to name. At least 50% of us were suffering from diarrhoea at a time when the British army doctor had no supplies except for a weak solution of iodine and charcoal he made from burning wood. We hadn’t washed for weeks and wore what we stood up in. Food consisted of a starvation diet. Lukewarm mint tea and a three-quarter share of a large hard biscuit was breakfast. The big meal of the day was lunch which consisted of a breakfast cup sized portion of soup, mainly water, laced with a small part of rice, barley or peas which gave the illusion of being fed. The evening meal was more tea with a piece of brown bread equal to a thick slice of a sandwich loaf.

"Left Salonika on July 22, 1941 arriving seven days later at Lubeck, near the Baltic sea, in closed cattle trucks looking and feeling like a crowd of dirty hoboes. We had been issued with sufficient food to last two days, hard white biscuits which needed a hammer to break and a small tin of meat about the size of Heinz baby food. At the camp we were deloused and had our particulars and fingerprints taken. After being given a metal identity disc we were allotted to rooms, ten men to each room. The camp itself was in fairly good condition being a former training camp for the German army." (Lister, 1993:84)

From Lubeck Ron and fellow Australian officers were transferred to other camps. On October 9, 1941 they arrived at Dössel-uber-Warburg about 60 miles north of Frankfurt and later moved to a camp at Eichstatt north of Augsburg. At Warburg in 1942 Ron recalled, "washing facilities in winter were scarce as most of the water pipes froze up. With typical German inconsistency they ordered that colonels only would receive a weekly hot shower, the exception being anyone who presented himself to the German doctor and showed proof of being infested with lice. He, together with his room-mates, would then have a hot shower at some future date - perhaps anytime up to a month later." (Lister, 1946)

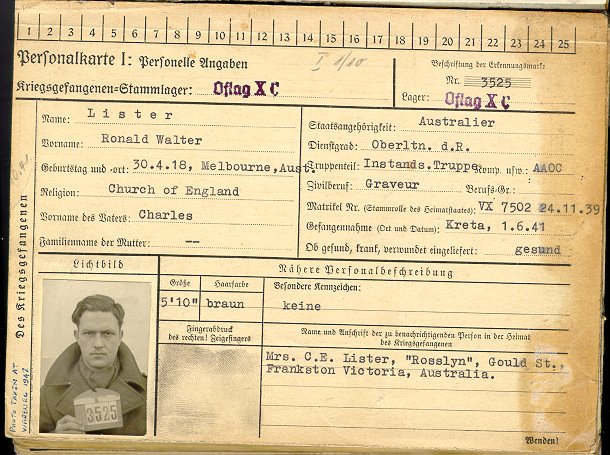

Ron Lister’s German identification papers as a prisoner of war.

Under the Geneva Agreement, an international treaty signed by many nations, officer prisoners of war could not be put to work by their captors. Neutral countries such as Switzerland and Sweden provided inspectors to ensure this condition was observed. Consequently, prisoners had time to engage in a variety of pursuits. Drawing upon the skills and knowledge of the people in the camp a variety of educational programs was organized. There were gardening classes, language classes, drawing lessons and lectures on military tactics and historical topics. There were people in the camps who completed university degrees and professional qualifications while there. Libraries were created from books sent by the Red Cross and these same parcels contained playing cards, board games such as chess and backgammon, table tennis bats, balls and nets, records, dice and all those games needed to wile away the boring hours. Orchestras and dance band were formed and performed at camp concerts which were important events and helped to keep men entertained and occupied. Sporting activities were also arranged for those interested. At Warburg many men became engaged in planning, organising and conducting escapes. Tasks included acting as lookout men, known as stooges, to give warning of an approaching German, making maps, stealing German property, and tunnelling in order to get bodies outside the wire.

Being a trained engraver Ron Lister found his services requested to engrave with unit badges and names cigarette cases, mugs and matchboxes of his fellow prisoners. "The largest engraving job that I under-took, not for gain, was engraving the badges of the Scottish units on the Staff of the Drum Major of the Pipe Band. This Baton was a masterpiece, being made up of odds and ends of Chromium light fittings, complete with chains." (Lister, 1993:102) It was while in one of these camps that he learned the skills of bookbinding and in turn trained others. "In the early days a lot of the time we sat around and talked about the Greek and Crete campaigns and about the inefficiencies we had seen." (Whitehead, 1998) One instance he recalled was the action of the British headquarters staff in Athens in April 1941. "I had to go to the headquarters and found that officers were only available from 10 to 12 and after 3 o’clock if they managed to get back from lunch. Yet this was at a time when the Germans had broken through in northern Greece and the British, Australian, New Zealand and Greek forces were in retreat."

During the last days of the war the Germans transferred their prisoners from Eichstatt to Moosburg a camp thirty miles north east of Munich. "We marched for five nights before arriving at the Moosburg camp. We refused to march in daylight owing to being shotup by Mustang Fighters of the U S Air Force when we started vacating Eichstatt. Fifteen men were killed and more than fifty were wounded," explained Ron. (Whitehead, 1998) It was from Moosburg that about 40,000 prisoners from all the nations of Europe were liberated by General Patton’s 7th Army.

The day after their arrival at Moosburg an American plane dropped leaflets over the camp warning that if any attempts were made to move any POWs from the camp, the camp staff would be held responsible. It was eight days later that the camp was surrendered. Ron recalled, "Around 1130 hours loud cheering came from the Lagerstrasse and we flocked out to see the cause. Dozens of Jeeps and American tanks lined the road with the occupants tossing out cigarettes and chocolates. It was marvellous. We had won! Despite all the set backs earlier in the war we always knew we were going to win. We just had to beat those bastards whatever happened." (Lister, 1993:140)

Ron and other former prisoners were flown to France, spending VE Day (Victory in Europe) at Rheims The following day on May 10, 1945 they were ferried by air in Lancaster bombers to England where they were deloused and fitted out with new uniforms On June 18, at Liverpool, Ron embarked on the troopship Stirling Castle for the journey home via the Panama Canal. After a train journey from Sydney he arrived in Melbourne on July 24 and left the army on April 24 the following year after 2022 days of overseas service.

When asked what were the major things he learned from his years of being a prisoner he replied, "patience and tolerance" and told the story of himself and a fellow prisoner. "We were sleeping in two tier bunks. I was on the top bunk and he was below me. At night I would be in that happy stage of just dropping off to sleep and he would start to hum a tune then he would take off his boots and drop them with a loud thud to the floor. Initially it annoyed me a great deal. Living in cramped conditions in a hut with 30 men, where food was scarce, with no one wanting to be there meant there were some tense times. The practice of the English prisoners, no matter what the weather was like, was to throw open all the windows at night to let the air in to the hut. Later when Canadian prisoners joined us they objected, particularly when snow was on the ground outside. Their solution to the problem was to nail all the windows up so they could not be opened." (Whitehead, 1998)

Ron married Constance Russell on September 8, 1945 at St Chad’s in Chelsea after being apart for six years. They set up home in Parkdale. Leaving the army he returned to the civilian occupation of lithographic artist working at the Argus Newspaper until its demise in 1957. Then followed employment with other printers until his retirement.

Ron has been actively involved with the Anglican church over many years including a period as a choir boy at St Augustine, Mentone and more recently as church warden and vestryman at St Aidan’s, Parkdale. In addition to his work for the church, Ron has been active in army associations, the Australian Red Cross and local community organisations such as the Southern Opportunity Shop at Mentone and the Mordialloc Historical Society. His skills as a handyman are highly prized by these local organisations.

In recognition of his community work Ron Lister has been awarded the Red Cross Long Service Medal, The Mordialloc City Council Community Service Award, Mordialloc Rotary Club Community Service Award and the Australia Day Committee: Neighbour of the Neighbourhood.