Sandringham Breaks with Moorabbin

On 28 February 1917 the Victorian Government Gazette noted that part of the Shire of Moorabbin had been severed and proclaimed a municipality in its own right. The new municipality was to be known as the Borough of Sandringham and the gazette notice marked the end of a thirty-two year struggle by residents of this bayside settlement for separation from Moorabbin. On six occasions between 1885 and 1916 petitions seeking severance had been presented to the Minister of Public Works and on each occasion the Moorabbin Shire Council, which was dominated by market garden interests, vehemently opposed the move. Thomas Bent, a Moorabbin Councillor as well as Member of Parliament for the district, actively thwarted the first four attempts.

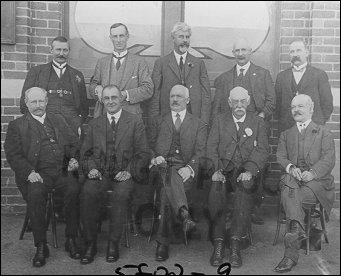

First Council Sandringham From rear left: Cr Hearndon, Cr Belyea, Cr Knott, Cr Farrant, Cr Hartsman, front: Cr Grace, Cr, Champion, Cr Ferdinando (Mayor) Cr Kelly, Cr Snowball M.L.A. Courtesy Sandringham and District Historical Society.

In 1885, what became the municipality of Sandringham (i.e. the suburbs of Hampton, Sandringham, Black Rock and part of Beaumaris) was included in the Shire of Moorabbin’s West Riding which was bounded by South Road, Point Nepean Road, the Mordialloc Creek and the foreshore. The expense associated with the maintenance of Point Nepean Road was one of the underlying causes of the entire thirty-two year campaign and it was to have a considerable bearing on the original decision to petition for severance. The failure of the first two petitions related to this road.

For municipal councils of the nineteenth century, finding money for capital works was a continual problem so the requirement that councils take responsibility for the upkeep of arterial roads within their boundaries created a heavy burden. Once road tolls were abolished completely in 1878, for those responsible for main roads used by ‘outsiders’, the financial difficulty of their maintenance was exacerbated. Rate monies were crucial and, in order to spread the burden on a basis that appeared equitable, portion of such a road was included in each internal division of the municipality. Thus portion of Point Nepean Road was included in all three Moorabbin ridings and it was used as the boundary between the East and West ridings. Each was made responsible for half the cost of maintaining this section, a burden which was constant because of the road’s heavy use as the route to and from market by Moorabbin’s large market gardener population. A claim that ‘either the north or the East Ridings or both, owed the West Riding between 500 and 600 pounds on the Point Nepean Road Account’ provided the catalyst for the original decision to petition for the creation of a separate municipality. (Southern Cross, July 19, 1884)

The severists of the nineteenth century, arguing that West riding had ‘different and distinct interests’ from the remainder of the shire, sought to separate the entire riding. There was some evidence to support their argument for a study of the 1885 ratebooks shows that while the North and East ridings were strongly dominated by market gardeners, West Riding was much more diverse. Nevertheless, a substantial 46% (in actual number 172) of West Riding ratepayers were primary producers and, as all were ratepayers, they represented a significant force.

The validity of their argument notwithstanding, the severists were less concerned with the nature of ratepayer interests and more concerned with their own business affairs for Harold Sparks, who organised the petitions of 1885 and 1887, was in the employ of Charles Henry James, one of Melbourne’s notorious 1880’s land boomers. James, who had extensive holdings in the Black Road area, saw severance as a means of increasing his own ability to control development. A separate shire of the area encompassing his holdings would have enabled James to nominate his own candidates for council and thus to have considerable say in how rate monies were spent. Even more importantly, it would have enabled him to provide the area with his own public transport system in the form of tramways for, although the railways were government owned and operated, ‘in the outer suburbs almost anyone could start his own tramway system, given the formality of municipal approval’. (Cannon 1977:44)

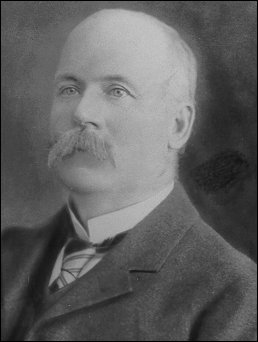

To the land boomer of the 1880s, the availability of public transport was vital. In order that land could be bought, sold and re-sold at inflated prices, it needed to be readily accessible and the government funded railway provided the most convenient means of achieving this. Failing this, a privately owned tramway system provided a second option. But both these possibilities were denied landowners in Moorabbin’s bayside area by the deliberate interference of a second land boomer, Thomas Bent. Bent, as M.L.A. for the district and a municipal councillor for both Moorabbin and Brighton, was a dominating force in the area. For Bent, with his large tracts of land in Brighton, hopefully to be sold at a healthy profit, to provide ready access to other bayside blocks would simply have created undesirable competition. Thus an 1881 request to Bent, as Railways Minister, to extend the Brighton Beach line an extra two miles to Picnic Point (later re-named Sandringham) fell on deaf ears as did an 1883 proposal by a group of local residents that they construct a tramway to Picnic Point at their own expense. The railway extension to today’s suburbs of Hampton and Sandringham was not opened until late in 1887. That it was opened at all was associated with the support given to Bent’s opposition to severance by West Riding resident, Moorabbin Shire councillor David Abbott. When opened, the line passed through Abbott’s Sandringham Estate with the terminus ‘about a quarter of a mile beyond Mr. Abbott’s residence.

David Abbott and wife Courtesy of Sandringham and District Historical Society.

Twentieth century studies of the nature of the community isolate the twin characteristics of territory and social cohesion as basic elements. As an extension of this proposition it is recognised that in order to become a cohesive group, individuals with common interests must have adequate means of communication. Bent, demonstrating the shrewd understanding of individuals and situations that was a hallmark of his career, identified, and exploited both these factors. In 1885 he deliberately played off the lack of cohesion between the market gardeners and the remainder of West Riding ratepayers as he forced Sparks to withdraw the severance petition by placing in jeopardy a 10,000 pound loan being negotiated by the council. The main purpose of this loan was the construction of a steelway on Point Nepean Road. A steelway consisted of two strips of steel placed along the length of the road a cart width apart. Horses would plod along between the strips while the cart wheels ran along the steel. For market gardeners who regularly took their produce to market, it was a particular boon and one which West Riding’s market garden element was not likely to be prepared to forgo.

In 1887 the number of gardeners in West Riding had dropped in total to 150 and represented 21% of resident and 15% of all the riding’s ratepayers. This time Bent focused on communication. He first shrewdly drew attention to the lack of internal cohesion by having an associate, Thomas Crisp, circulate a petition seeking to have the area north of Bay Road annexed to Brighton. This highlighted the fact that the northern and southern ends of the West riding were serviced by two different railways. At Bent’s instigation, Minister of Public Works, John Nimmo, rejected the petition because, under the proposed boundaries, Point Nepean Road would split the townships of Cheltenham and Mordialloc between two shires and ‘this would never do’. (Southern Cross July 16, 1887)

Following the failure of these attempts, severance was not again attempted until 1901. By this time the focus was entirely different for, by the turn of the century, with altered priorities in the inner-Melbourne area, the city was becoming increasingly suburbanised. As secondary industry moved in, those who had lived in the city centre were forced to relocate. This they did by moving out along the existing public transport routes. There were clear signs that Sandringham’s development was following this pattern. Aside from a steady increase in ratepayer numbers, particularly those who were actually resident, the records show a noticeable upward movement in the number of outward passenger journeys from Hampton and Sandringham railway stations, an indication that residents were commuting to the city each day.

This suburbanisation was reflected in all aspects of the severance campaign. The leading force, Benjamin James Ferdinando, was an accountant who lived in Mills Street, Hampton. As one who commuted daily, he was representative of the type of settler being attracted to the district. Throughout all the years of campaigning, committee members of the Sandringham Severance League were also exclusively suburban dwellers. Control of rate monies remained a major concern but, in contrast to the severists of the 1880s, those of the twentieth century were more specifically aware of their requirements. The suburban focus of these requirements was evident in a circular to ratepayers when severance was achieved in 1917. It emphasised the need for the new councillors to carry out ‘the aims of those who struggled for the past 14 years’, and included ‘Electric light, Water and Sewage Throughout the Borough’ and ‘Better and Improved Foreshore Control’, along with the introduction of ‘The proper and Economic Supervision of all Works’, ‘New Building Regulations’ and ‘Strict Compliance with Board of Health Regulations’.

Benjamin James Ferdinando.

The ‘different and distinct interests’ which were beginning to become apparent in the 1880s had become very evident by the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1901 just 15% of West Riding ratepayers were primary producers and by 1915 this had dropped to 9%. In the same years, the figures for North riding were 50% and 45% and for East riding 52% and 42%. Following the rejection of Sparks’s 1887 petition, West Riding had been divided into two, West and South Ridings. South Riding, which took in the bayside settlements of Black Rock, Mentone and Mordialloc, was also beginning to show signs of suburbanisation but the number of outward passenger journeys from Cheltenham, Mordialloc and Mentone suggest that this trend was not so marked as with Hampton and Sandringham.

Ironically, it was this growing suburbanisation that was the very reason for Moorabbin Council’s continued reluctance to part with its irritating bayside territory. The council was constantly having trouble making ends meet and, while rate receipts from North and East ridings remained basically unchanged, the increasing settlement along the bayside brought a corresponding welcome increase in rate revenue. At the same time, the beach park was also generating much needed income in the form of bathing box fees, beach dues, rent for baths, camping fees and the like.

In blocking the 1901 petition, Bent again played upon the differences between the two sections of Moorabbin’s bayside territory, but this time he reversed the tactic of 1887. Although the plan was to sever West Riding along its new boundaries, Bent forced the inclusion of South Riding. Then, as council president, he opened negotiations for a further loan, in order to provide the shire with a water supply. While portion of West Riding was already connected to the ‘Yan Yean’, South Riding was not, so once more Bent was able successfully to play upon the internal differences in order to weaken public support. An interesting outcome of Bent’s manipulations was that, while the majority of South Riding residents voted against the severance move because they had no interest in common with Sandringham … [and] the division would be better if Mentone, Mordialloc and Cheltenham were together’, the residents of Black Rock voted in favour and elected a committee ‘to work on the same lines and in conjunction with the Sandringham committee’. When the petition was presented, the proposed boundaries reflected the varying decisions of South riding settlements. The rejection of this petition was simply gazetted without any reason being recorded but in 1910, in a history of the severance campaign, the Brighton Southern Cross claimed that:

"The Peacock ministry was in power at the time but depended upon the opposition for a measure of support. Some of the opposition were against the petition and, as the Government could not afford to ignore them altogether, the petition was dismissed and the refusal advertised in the Government Gazette."

Brighton Southern Cross, June 4, 1910.

When severance was again considered in 1907, the proposed boundaries were altered only slightly from those of 1901. Bent, by then Victorian Premier, was overseas for much of the time and it seems likely that the severists had hoped to counter his interference by having the new municipality proclaimed during his absence. But, on his return, the petition was still to be considered and Bent rendered it invalid by having a back-dated clause, which stipulated that before June 1910 no municipality should ‘be constituted or united and no portion of any municipal district …[should] before such date be severed and annexed to another municipal district’, inserted into the Municipal Endowment Act. (Victorian Government Gazette, December 23, 1907)

By the time the 1910 petition was being drawn up, an interesting change had come over the campaign. Aside from the fact that an increased population allowed the committee to petition for the creation of a borough rather than a shire, for the first time there was evidence of an interest in the internal composition of the municipality the severists wished to create. At a public meeting they unanimously agreed to ‘make the district a coastal suburban borough … where the interests of all were as identical as possible’. Accordingly, Moorabbin and Highett were eliminated because ‘there was not similarity of purpose or community of interest’ and Mentone, Mordialloc and Cheltenham continued to exclude themselves ‘because the people in that locality were fairly divided’. This left Hampton, Sandringham and Black Rock with the proposed boundaries. With one minor alteration, the 1910 boundaries remained those of the Borough of Sandringham when it was constituted in 1917.

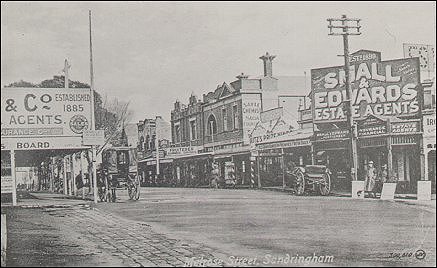

Melrose Street, Sandringham opposite railway station c1920.

Bent had died in September 1909 so his interference was no longer a factor. However, government policy at the time was for amalgamation rather than the creation of new municipalities and, although this was largely directed at municipalities which were no longer viable because gold mining had petered out, Minister of Public Works, W. L. Baillieu, rejected the petition. But, in doing so, he indicated that ‘as there was community interest between Sandringham and Brighton’, he would be prepared to consider introducing a Bill ‘enabling portion of the district to be severed from the Shire of Moorabbin and annexed to the Town of Brighton’. (Southern Cross, June 17, 1911)

Opinions expressed at the well-attended, noisy public meetings called to discuss Sandringham’s municipal status revealed none of the community of interest with Brighton that Baillieu had claimed.

‘Joining Brighton was like trying to revivify a corpse’.

‘We are dead now, but if we join Brighton we will be dead, dead, deader’.

‘The minister has suggested a certain course, but it is not compulsory that we should carry it out’.

‘It [severance] was not dead. It had been a burning question for 25 years, and they had as good a chance now as ever they had’.

Southern Cross, August 12, 1911.

Although a petition was drafted and negotiations with Brighton begun, by March 1912 members of the newly-formed Annexation League were forced to inform Baillieu that ‘the result of their efforts was not sufficient to warrant … proceeding with the petition’. (Southern Cross, April 26, 1912)

By the time the final severance petition was being circulated the strength of community which had developed in Sandringham was quite evident. The Progress Leagues of Black Rock, Sandringham and Hampton joined the Severance League en masse, individual residents gave personal and financial support, worked rosters outside the Hampton and Sandringham railway stations and canvassed individual streets for signatures. When Minister of Public Works, W. A. Adamson, heard arguments for and severance, ‘A Monster deputation including about 100 residents from Sandringham, Hampton and Black Rock ... urge[d] reasons in support of the petition’ and Ferdinando was able to state that ‘With regard to the numbers of ratepayers who have not signed the petition, you can count them on your fingers’. Adamson indicated that he was impressed by the arguments in favour of severance. This was reflected in his decision which was published in the Victorian Government Gazette of 28 February 1917.