The Chelsea ‘Gut’ Factory

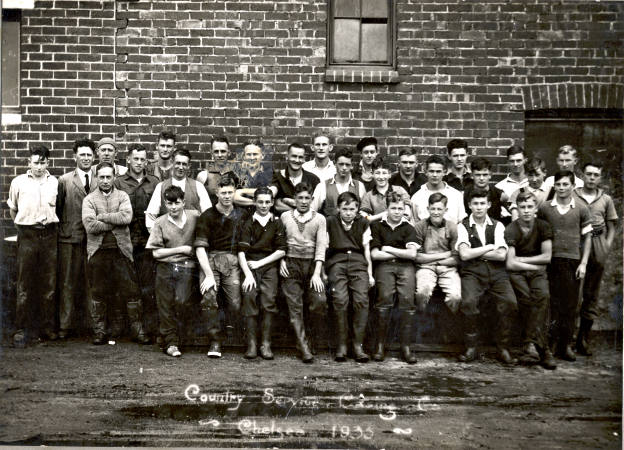

Male employees of Chelsea Casing Company, 1935. Courtesy: Chelsea and District Historical Society.

For more than fifty years the Gut Factory was a feature of the environment at Chelsea, not because of its physical presence but because of the stench it created. The business was started in 1927 as the Country Service Casing Company, initially with three directors but joined by a fourth twelve months later. The directors were Mr Northfield (manager), Mr Aurish, Mr Stan Cook and Mr Fred Brunstein. Located in Argyle Avenue on the corner of Scotch Parade the small factory was surrounded by paddocks.

Sometime later an American, Mr Feldman, established a second company on the same site. This business was called the Pacific By-Products and worked in association with the Country Service Casing Company. Subsequently the latter company was bought out by Mr Feldman and its business integrated into that of Pacific By Products.

These companies were engaged in collecting the gut of animals slaughtered at country abattoirs and using it to manufacture high quality tennis strings, sausage casings and medical sutures. Lorna , a former employee described the process. “The gut was cleaned by men in one room and then brought to a second where it was cut into ten yard lengths. Before being cut it was about thirty yards long. The length was then placed on a long nozzle and water poured into it. The gut was graded into different sizes or standards using gauges. Anything that was holey was rejected and sent to the Casing Works where it was made into tennis strings or sutures.”

The waste material was discharged into trenches and holes on the property releasing a very strong unpleasant odour which would waft over the area with the prevailing winds causing much discomfort to Chelsea residents. Working in the family business as a young girl Margaret Jacobs recall electricians returning from correcting electrical faults at the factory with the stench permeating their overalls and shoes. Lorna during the thirty years employed at Pacific By Products had no trouble with the stench because she had lost her sense of smell as a child. Nevertheless she remembered instances of new employees lasting only a few hours at most because they could not stand the overpowering odour.

The medical officer for the City of Chelsea who was required to visit these factories was reported to say that he would close the factory down tomorrow except for the fact that too many people would be put out of work if he did. The Country Casing Service Company was formed just before the Great Depression and was providing one of very few employment opportunities in Chelsea during a very difficult period for many families. Boys and girls leaving Chelsea State School at age fourteen found few openings. Some became grocery boys or shop assistants. But even here there were few opportunities as small businesses tended to employ family members. There were no other factories except for a plaster factory at Bon Beach. Many Chelsea residents travelled to Richmond to work in the factories located there.

Lorna said her family was “hard up” during the Depression. “Other kids had a lot more than we had. My mother went out and did peoples washing and washed floors to get money. My dad had a horse and cart but there wasn’t much work for him. I remember the council used to bring in apples from the orchards and half would be rotten. They would be dumped and you could go up with your pram and load it up to take home. They also did this with onions. This helped. Clothes were hand me downs.” There were other families experience difficulties and it was not unusual for boys and girls to go to school without shoes and socks. In this situation the employment provided by the gut factory was most welcome Lorna said.

Lorna joined Pacific By-Products shortly after leaving Chelsea State School at fourteen years of age. Two older sisters were already employed there. Conditions were trying. Water was constantly flowing over the concrete floor with the employees in gumboots standing on wooden boards. They had to walk through the water to place the graded gut in the appropriate boxes with salt. It was freezing said Lorna. Later, bowls of warm water in which employees could place their hands were placed on the benches and a big fire was set in the workroom which gave out a good heat, both of these provisions helped to relieve the situation. The wooden benches were replaced with stainless steel units and at that time employees had to wear uniforms which were supplied.

Despite these conditions Lorna said it was a good place to work. Work started at 7.30 in the morning and finished at 4.15 in the afternoon. There was a morning tea break and three quarters of an hour was provided for lunch. There was a lunchroom but facilities were very basic. There was provision for sick leave and two weeks holiday was granted every year. The workers had to apply for leave as the factory did not close down. “The management tried to let people who had kids have the school holidays and those with working age kids could get them jobs down there during school holidays”, Lorna recalled. There was a social club which was run by two of the workers, Ron and Eric Musgrave. The club organised outings for the families of employees and there were games nights where they played table tennis, and quoits. On other occasions there were dances and picnics. Employees contributed two shillings each week to pay for the activities. Ron Jacobs remembers the local fire brigade members being invited to take part in games nights.

The Chelsea News October 14, 1940 reported that the factory had applied to establish a piggery and had received Council permission, “as beyond Fowler Street is for factories and industry” However, there is no evidence that the piggery was never proceeded with.

Mr Feldman was the owner of Pacific By Products. An American, he came to Melbourne each year to talk to the manager, Mark Boffa in the Melbourne office and to call in to the factory at Chelsea where George Rogers was the foreman. Lorna recalled that Mr Feldman would put on an eight gallon barrel of beer for the employees each Christmas. In 1978 after Mr Feldman died the buildings were demolished and the land was sold. One low-lying section of the land was purchased by the Chelsea Council and filled with hard waste. Other parts eventually became the site of housing. Lorna commented that the closure was a bit upsetting to her and others. She had been an employee for thirty years. “But we got what we were entitled to. They were good people to work for.”

Employees at the Chelsea Casing Company in Argyle Ave and Scotch Parade, c1930. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society.

Footnotes

- Inchley, C. Recollections of Early Chelsea, 1940.

- Whitehead, G. Talking with Lorna, Chelsea and District Historical Society, 2005.