Highett in the 1930s

Aerial of Sandringham from Hampton Football Reserve towards Highett, 1922.

When St Stephen’s Anglican Church was built in 1931 there were approximately 260 buildings in the whole of Highett from Bluff Road to Chesterville Road and even then some of these would today be registered as being in Moorabbin. The area itself was officially listed as a post and telegraph office township 11 ¾ miles from Melbourne with a recreation reserve and a hall, and that single fares by train were 1/2 ½d first class and 1/0 ½ second class ( or a little over 12 cents and 10 cents). It was also listed as a market garden district. Omitted was the fact that Williams aircraft factory (which was earlier called Williams aerodrome) was on the land between Highett and Bay Roads commencing at the Graham Road corner.

There was still plenty of land for sale but with the financial depression that existed during that time worsening few people could afford to run the risk of investing in property that might over night lose most its value. For instance 10 acres of land on Highett Road near Spring Road and backing towards Bay Road (with a house on additional land thrown in) was offered for sale at £2,000 ($4,000) but there were no takers, despite the assurance that it was located “ten minutes walk to tram”. Yet this was by no means peculiar to Highett it was typical of prices being asked throughout the length and breadth of Moorabbin.

One of the two sealed roads in Highett was Highett Road which was a narrow ribbon of bitumen with wide earthen strips on either side and in most cases the streets could scarcely be defined – they were merely parts of paddocks. Graham Road was unmade and people wanting to sell their land along the side of this thoroughfare (named after a previous owner Norman George Graham) found their attempts to put the land on the market thwarted because it had not been gazetted as a government road. Nepean Highway of course was sealed but like the central road through the small shopping area (Highett Road) it was also hopelessly narrow for the amount of traffic it carried and between this and potholes along with ragged edges accidents ( often of a serious nature) occurred regularly.

Junction of Graham and Highett Roads, 1932. Courtesy John Brooks.

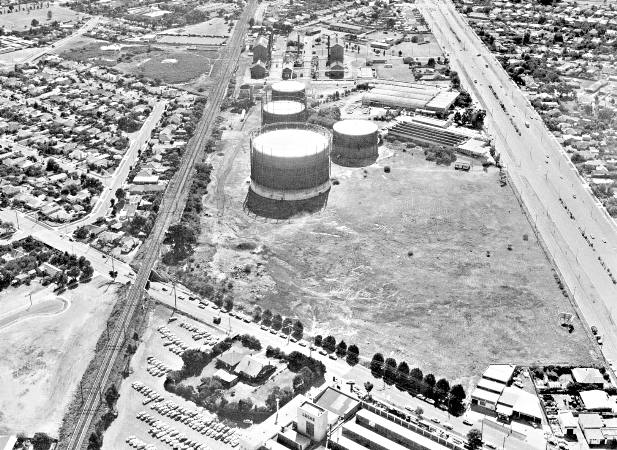

The small gasometers of the Brighton Gas Company that stood centreway between Graham Road the Highway matched the rural setting. There were six well spaced houses along Graham Road while on the west side of the Nepean Highway between Highett and Bay Roads along with front of the gasworks were the market gardens of Thomas Eastaugh, A Williams, George Roberts and A E George with the poultry farm of Siede and Sons in the middle. On the corner of Bay Road was a small country cottage owned by one of the Brough families and insulated with grapevines, at the rear of which was a well kept lemon grove. At the point where Bay Road meets the Nepean Highway was an electric light pole placed in the centre of the road, apparently for the purpose of dividing traffic entering and leaving the Highway. This it did quite successfully as cars driven by fast cornering motorists collided with the light pole instead of each other while complaints were laid by all except the panel beaters.

Aerial view of Highett Gasworks, c1980.

On the present site of the Lucas Electrical Company (now part of Westfield’s Southland) where Cheltenham begins was another home owned by the Broughs on property bordered by 100 foot high pine trees which stretched along the Highway and down Bay Road almost to the low level railway bridge that local people referred to as “the bridge of sighs”. Yet the same bridge provided great entertainment for those living nearby for more than 80 years when heavy downpours of rain turned the roadway beneath it into a wide lake. Residents who saw horse drawn vehicles bow out to motor cars often told how horses stood and refused to enter the water, then with the advent of the motor car brave motorists drove into the swirl to have their passages halted midway as water entered their exhaust pipes. As the bridge grew older and the motor trucks grew taller however there began a new year during which the latter frequently became locked under the bridge and railway officials belated trains and shook fists at drivers who tried to free vehicles by using tow trucks in their fear that the bridge might also be towed away. In the long run, and just a few years before the bridge was replaced much of the entertainment went out of the bridge incidents when a schoolboy thought up the idea of letting down the tyres of trapped road vehicles and backing them out under their own power.

Highett’s sports reserve in the 1930s was the Turner Road Reserve which also had a reputation for being flooded, and often when sportsmen relied on it being dry. The Public Hall was the old timber building where the Highett library is now sited. The amazing thing about this structure is that it could seat about 500 people, which amounted to over a quarter of the town’s population. It was widely known as the local picture theatre, mainly because most citizens only attended the building when films were being shown. The same hall saw silent films give way to the talkies and black and white to colour and ultimately its own picture shows gave way to home television in the late 1950s. Then the Moorabbin City Council bought the building when a few years later it began to fall into a state of disrepair and after dismantling the old “flicker house” constructed the present day library in its stead.

Archery on the Turner Road Reserve, Highett c1960. Courtesy Val Dennis.

There are still many people living in Highett who remember the old public hall being used for dances, flower shows, church services and for function held to entertain servicemen during the World War II but Saturday afternoons and certain week nights were often set aside for film shows., Heating in theatres and halls was note as prevalent as it is today and jumpers, coats and heavy overcoats over them were standard wear for a visit to the “pictures” at Highett during the winter months. Perhaps it was the wintry coldness of the building also that caused the 3KZ Social Circle’s Highett Branch to hire the hall for its weekly Wednesday Night 50/50 dance which were held there from the 1930s onwards. This group was renowned for the fast moving mid-week dances that were a regular function throughout the war years.

The Highett Public Hall struggled on for twelve years in a hopeless fight to survive in competition with the household “box” but by then a new opponent had come on the scene in the form of ‘drive-in’ picture shows, one of which began to operate two kilometres away from the once versatile hall of entertainment, which in the new era of ‘wheels for everything’ became redundant. The old landmark finally disappeared at the hands of the wreckers during the first half of 1969 and on August 1st of the same year the small brick library of today opened in its place in the midst of a modernised and enlarged Highett Shopping Centre. Yet it had to be expected; Highett’s population in 1945 (just prior to the end of World War II) had expanded from approximately 720 to nearer 1,200 and was still on the increase.

Demolition of Highett Theatre, 1966. Courtesy Leader Collection.

It was a far cry from the beginning of the 1930s when a walk down Highett Road from the hall revealed only the following business houses:- First came the premises of Herbert Baker – he of course was a baker; then came Henry Chamberlain’s grocer’s shop; Edward White’s barber shop; Clarence Judd’s Post Office agency, confectionary and cake shop; William Silverwood’s estate agency and Comber’s woodyard. Scattered around the Station Street area and back along Highett Road were Harry Bevis’s produce store; Horace Piper’s and Alf Soul’s fruit shops; Fred Coleman’s grocery store and Alan Walker’s butchery.

Highett General Store and Newsagency, Reynolds and Company, c1925. Courtesy John Brooks.

A ride in the train from the city took the traveller into the bush almost as soon as Bentleigh was passed and by the time Highett was reached the scene was one where there was only an occasional building in a paddock of sandy loam, with clumps of ti-tree here and there, an occasional gum trees and stands of English pines planted just a century beforehand as a wind break, possibly by William Highett on his cattle run. Beyond Bluff Road could be seen the herds of cows that went to make up Ralphs’ dairy – one of the biggest south of Melbourne.

School children had a choice of schools – at Sandringham, Moorabbin or Cheltenham (but not at Highett) and the usual method of transport was by foot, through the ti-tree tracks and around the swamps. Mothers gave their usual send-off advice “… and watch out for snakes, and if you see any don’t go trying to kill them – just make a noise and they’ll disappear into the grass; they’re more frightened of you than you are of the!”, and just who was she kidding?

In Donald Street there were eight houses (two of them vacant) and the dairy of W Snelling and Son. The other residents were F A Darby, George H Styles, Percy King, E P Hawkes and John Thompson. In Middleton Street there were three; James Angeli, A H Jackson and L H Waite, who was a surgical boot maker. There was only on house in each of Alfred, Allan, George and Herbert Streets (with the latter one being vacant) and it will be noted that all bore the Christian names of men. Clonmult Avenue carried two homes while Baldwin Street again had one and Aster Crescent six. Vida Crescent was another one house street but against this was Highett Road with 48 houses (including some dwellings attached to shops) from Nepean Highway to Bluff Road as the Highett thoroughfare with the most homes next to this in number of residents was Beaumaris Parade with 13 homes.

Other streets and the number of homes they contained were as follows: Thistle Grove – 1; Tennyson Street – 2; William Street – 2’ Spring Road and Rose Street – 3 each; Turner Road – 4; Train Street and Sandford Street – 6 each; Station, Tibrockney and Henry Streets – 7 each; Francis Street – 5; View Street – 9; Worthing Road – 10 and Railway Parade – 12. Add them up and you get not only the scattered housing layout of 1931 but an idea of the attitudes of Australians who prior to World War II regarded spacious living as something of a birthright. This particular theory was very strong among people born towards the end of the 19th century who, by the way, were the average householders around Highett and Moorabbin generally during the 1930s and even in the 1950s – when fast talking developers veiled as town planners were sent to Moorabbin to convinced members of progress associations that the correct mode of life was to “build dwellings up instead of out”. It was these “turn of the century” born Australians who took up the cudgels against the move that might well have led to suburbs like Moorabbin becoming hideous high rise areas like ones sees in Hong Kong, or even on the Melbourne skyline as can be witnessed from near the corner of Bay Road and George Street.