Fixing the Jury

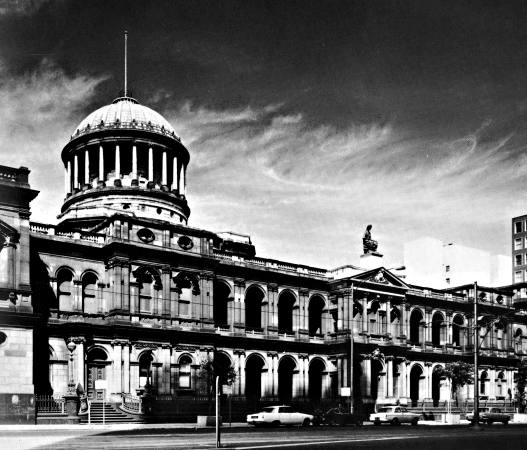

Melbourne Law Courts.

In December 1920, sixteen year old Arthur Ernest Dowling (Ernie) found his mother locked in the kitchen of the family home with a near neighbour, Patrick Duff, at a time when his father was away. This was not the first time such an occurrence happened but it confirmed his suspicions that Duff and his mother were having an affair. This led to a shooting in which Duff was shot in the lungs and died. [1]

At the Coronial Inquiry, Coroner Cole found that Duff was ‘wilfully, feloniously and maliciously shot in the body and killed by Arthur Ernest Dowling’ and found him guilty of wilful murder. He was remanded in custody to stand trial in the Supreme Court on 15 July 1921.

Dowling’s verdict of wilful murder was not unexpected, but it would still have come as a shock to his parents. Verdicts by the coroner in the era were made with a strict logical view of the facts. So, with a shooting all that was required for a guilty verdict was a confession or a witness and Dowling was up against both. His only hope was a recommendation of nolle prosequi by the Crown Prosecutor on the grounds of his age and mental state. [nolle prosequi is a latin phrase meaning the prosecutor is dropping the case] But for a lad of his age, that would mean a bleak future for an indefinite period in a reformatory or mental institution.

Back at the Dowling farm, the day after the coronial inquest would have been one of reflection, bewilderment and perhaps sorrow for Ernie’s parents, Grace and Arthur, as the verdict began to sink in. It would take a miracle for their son to avoid a lengthy goal term at the Governor’s pleasure. Perhaps they were both privately hoping a miracle would happen.

The lucrative trade of jury rigging was a blight on the justice system in the 1920s. The ease of identifying witnesses and jury members meant a visit by a few shady thugs had a way of achieving a favourable outcome. All that was needed was a deep pocket and the right connections. And then there were the self-styled ‘legal advisors’ who could see the business opportunity of paying a friendly visit unannounced and offering advice on the finer art of obtaining justice. Judge Wasley, an experienced criminal court judge said that from time to time attempts were made to ‘square’ juries and the crime was difficult to detect and prove. He did acknowledge that on occasions attempts were successful but not to the extent that was sometimes thought. [2] However, it didn’t take long before the Dowlings were paid such a visit from a ‘shady thug’.

Shortly after 10.00 pm. the day following the inquest, Arthur and Grace were in bed when a flash of light from a motor car illuminated their bedroom. Grace rose thinking some friends were outside and opened the bedroom window to inquire.

‘Does Mr Dowling live here?’ came the voice from a man.

‘Who’s asking?’ asked Mrs Dowling.

‘Mr Lyon. There is a business matter that I would like to discuss.’ Arthur Dowling called Lyon to the back portion of the house where he later joined him there.

‘Are you Mr Dowling?’ began Lyon.

‘Yes.’

‘Father of the boy?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you want to get him off?’ asked Lyon.

‘Yes, certainly,’ Dowling replied.

‘Put it in our hands, and we’ll fix it up for you. I was asked to come down and see you.’

The reply caught Dowling off guard, but deep down in his heart, as a loving parent, his duty was to do all that he could for his son.

‘Who by?’ asked Dowling.

‘It doesn’t matter, no one you know.’

Dowling was now apprehensive about the conversation as they moved into the dining room.

‘You have nothing to worry about over the boy; if you put the case in our hands we can get him out of it all right’ said Lyon before continuing.

‘The men I work for – Stokes and Boardman – can fix the jury, and if we get eight of the jury we will be all right.’

‘Look, I need time to think it over. I’ll be travelling into town tomorrow to see my son’s solicitor. Have you worked with Mr Kelley?’ asked Dowling.

‘Yes I have and if you make inquiries you will soon confirm my credentials.’

The conversation ended with the arrangement to meet in the city the following day. [3]

On 26 June at 3.00 pm Lyon again paid the Dowlings a courtesy visit.

‘Mr Dowling, I have to ask if you will be applying for bail?’

‘Well, I intend on trying tomorrow, but …,’ replied Dowling reflecting his view that the chances were slim.

‘Good, very good. You will come and see me if you are unsuccessful and I will bring the boy home on Tuesday night,’ said Mr Lyon to Dowling’s astonishment.

‘And how will you do it?’

‘Never mind, Mr Dowling. I just know the ropes to pull; you have just got to go to the judge in the chambers….’

‘Well, I’ve already been there,’ Dowling cut in.

‘We can do it all right. Now about the trial, Mr Dowling,’ before continuing.

‘The boy is committed to the 15th, he won’t go up for three or four days afterwards. A panel of the jury comes out about 12 hours before. If we can fix them up we will be able to get a straight-out acquittal. We want to cut out this insanity stunt! You do no want the boy sent to the ‘rat house’ – they would drive him mad there – or the reformatory either; you want to buy a straight out verdict,’ explained Lyon as Dowling listened intently.

‘The jury pool consists of between 50 and 60. The boy has an unlimited challenge. We would have it fixed up with his solicitors; we would instruct the boy when to challenge.’

‘What would this cost?’ asked Dowling.

‘£300, Sir.’

‘I don’t …um… I don’t have that amount of money,’ before continuing. ‘I’ll have to try and obtain it from friends.’ [4]

‘No hurry, Mr Dowling. We have plenty of time.’

As Lyon left the Dowling home he remarked ‘Mr Kelley is all right. He is an Irishman; so am I. We will be in touch again shortly, Mr Dowling.’

The following week, Lyon received a private letter addressed to ‘J J Lyon, New Fur Co., Swanston Street.’ It read:

Richfield, Wells road, Mordialloc, 2/7/21

Dear Mr Lyon,

I have talked the matter over with my husband; he has spoken with friends about the money, and our sale is on Monday, so we may have enough cash for you. Come out Wed. night after dark, if possible, or any other night before Sat., we are busy just now getting ready for the sale. I do hope you can help us.

Yours truly,

Mrs Dowling

Two days later, Lyon again visited the Dowlings. But this time he suspected a trap.

‘Have the ‘demons’ been out here?’ inquired Lyon, meaning the detectives.

‘Yes; they came out to me about the boy. I made an application to the crown for assistance for his defence.’

‘Well this letter of yours. It has been examined by a ‘mate’ who believes it to be one of Piggott’s traps. (Piggott was a senior detective with the Victorian Police) It’s just what Piggott would do – send that out – and wait on the road to catch me.

It was indeed a trap as Lyon suspected, but Piggott would wait patiently in the wings for the right opportunity. That was to come at 9.00 pm on 7 July on Lyon’s final visit to the Dowlings. Waiting in an adjoining room was Plain-clothes Constable Andrew Francis Kennedy and he was armed with a revolver.

‘How’s the son?’ asked Lyon. ‘I want to help all I can for him.’

‘We’re still keeping on with our solicitor, Mr Kelley.’

‘Such a pity, Mr Dowling. Kelley is a fine lawyer, but has not been in the Criminal Court for years. Such men as Maxwell, Ah Ket, Sonemberg and Fogarty were all right. All you need is to mention my name and they will know.’

‘How do we get on if you approach a juryman and he ‘squeaks’ to the judge?’ asked Dowling.

‘Such cases do happen,’ Lyon replied. ‘That only happens in isolated cases like that of Khyatt,’ referring to the case of Henry Khatt who in April had made a clumsy attempt to approach the jury and was refused bail. [5] He doesn’t know anything about the game. The men I work for are different. Do you know Stokes and Boardman? They would shoot a man in Collins Street if he turned them down,’ before continuing. ‘It’s much easier to get out of a murder case than out of a burglary or shoplifting case. Eight juryman on the books, married men with four or five children will do the trick.’

‘I fixed up two good cases last week,’ Lyon boasted ‘There are 60 or 70 names on the list, and we generally know half of them.’

‘How do you know they will stick to you?’ asked Dowling.

‘They know those behind us would shoot them,’ referring to Stokes and Boardman.

‘Now, your case can be settled for £300 but I will require the money before the panel come out.’

Dowling handled Lyon a cheque for £250 dated 11 July and at Lyon’s suggestion, made out the butt as if the cheque had been given in payment for a Cadillac motor car. Lyon had barely grasped the cheque when out came Kennedy with his loaded revolver pointed at Lyon. In the ensuring struggle, Lyon threw the cheque onto the fire only for Kennedy to retrieve its burn remains. Shortly after, Piggott arrived and it was all over for Lyon and his enterprising scheme. [6]

This was one of the more sensational cases that came before the Cheltenham Court and few generated as much interest as the charge against James Joseph Lyon, 31 of Milton Street, Set Kilda with conspiring to incite the Dowlings to defeat the ends of justice. Indeed, so small was the Court that it was unable to accommodate the four honorary Magistrates who turned up to hear the case on Wednesday 13 July 1921. As the local Moorabbin News opined:

‘The justices of this district are noted for the manner in which they attend to their court duties, and in this regard they set an example to the magistrates of other suburbs, many of whom rarely attend courts, although it is the main purpose o their appointment … it was a long time since so many justices attended … and whether or not morbid curiosity was the cause we cannot say.’

For the men of the Bench, a case of this nature was uncommon. They were more accustomed with hearing cases involving petty crimes such as public nuisances, by law and traffic offences, theft and disputes than an intriguing case involving jury rigging. So it’s understandable when such a high profile case appears before the court the men of the Bench jump at the opportunity of hearing the case. The presence of the Melbourne press would ensure amble coverage and few men on the Bench shunned the limelight.

The length of the hearing – over three hours – was one of the longest on record. Senior Detective Piggott prosecuted while the defence argued it was the Dowlings who were the guilty party. Lyon was committed to stand trial in the supreme Court (General sessions) by the Bench which included Richard Knight, P.M., and JPs Le Page, Clements, Castle, Edwards, Hunter and Chadwick. Bail was set at £750 with a personal recognisance for the same amount. If Lyon was able to rig a jury, could he rig his own at the forthcoming trial? [7]

James Joseph Lyon, the enterprising furrier who had been in gaol nine times faced a lengthy prison term for attempting to ‘square’ the jury at Dowling’s trial. The sentencing judge, Judge Wasley observed that;

‘The case boils down to this; are the Dowlings telling the truth? Do you go to a manufacturing furrier to look after a case for you, or do you go to a solicitor? Was it Lyon’s object to assist persons he knew nothing about, or to interfere improperly with the course of justice?’ [8]

The verdict was three years hard labour.