Former foe honors Anzacs

For he today that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother

William Shakespeare, Henry V Act 4 Scene 3

Shortly after the 1939 Anzac Day service in Mentone, an article appeared in the Mordialloc City News with the headline "A friendly gesture: Former foe honors Anzacs“:

Many of those present at the Mentone memorial service on Anzac morning were curious as to the identity of a middle-aged man, of soldierly bearing , his coat decorated with strange medals, who, with his wife and two daughters, stood apart from the crowd and followed the service with respectful interest.

At the conclusion of the service a well-known citizen of standing approached the stranger and told him how much his gesture of goodwill was appreciated, and told him that on future occasions not to stand apart, but to join in with other citizens in honoring the fallen soldiers.

The stranger said he was hesitant to do so on this occasion, as some might not understand that he, now a citizen of Australia and a fugitive from Germany, was anxious as a former captain in the German Army and the possessor of an Iron Cross (which he was wearing) to pay his respects to the memory of Australian men who had died in the war. Returned soldiers who were present gave the ex-enemy captain a warm welcome.

In a world full of national antagonism, this little incident acts as a palliative.

This story had also appeared a few days earlier in both the The Herald (25.4.1939, article on page 1„ The Man With An Iron Cross“) and The Argus (26.4.1939, article on page 3„ Once an enemy“):

That man was my grandfather, Erwin von Gizycki, who had arrived in Melbourne the previous August as one of 12 passengers on board the German cargo vessel Wuppertal.

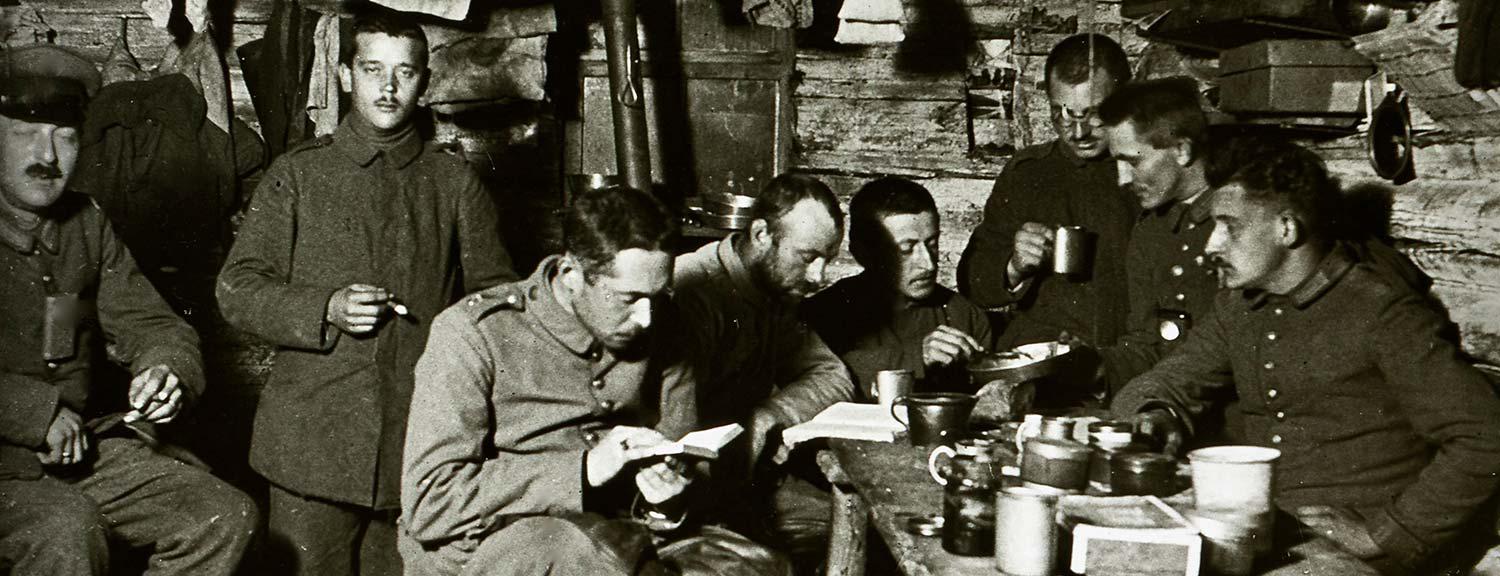

Erwin had considered himself a patriot, returning from Switzerland in 1915, where he had been living and working, to enlist in the German army.

His fortunes and his allegiances changed with the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany. Because of his Jewish background, he had to be dismissed from his position as the business manager of the electricity works in the German town of Saalfeld in 1936. His employers, however, continued to pay him a generous retainer and also financed his and then later his family‘s emigration (costs of travel and transport of belongings) after being granted residence permits for Australia. Those members of his extended family who did not or could not leave Germany were fated to die in concentration camps.

In a letter (dated 16 July 1940) to Roland Browne (Inspector in Charge of the Commonwealth Investigation Branch in Melbourne - forerunner of ASIO), Erwin described his situation in Germany:

My letter to Herr Ebbecke, the Chairman of our Board … reflects my true feelings. It was extraordinary what he and these other men had done for all of us. Not only had they taken upon themselves the dangerous responsibility of financially assisting us, outcasts, far beyond all usual limits, but they had done it in the most delicate form, carefully avoiding everything that could have hurt our sad feelings. Complimentary as it was, all this interest and helpfulness and the assurance that it was a duty of honour for them, it could not entirely veil to us the fact that we existed, for nearly three years from a very kind, very tactfully concealed charity. We greatly appreciated the sincere sympathy of these and many other friends, but the situation as a whole remained unspeakably humiliating.

It is this memory, unforgettable for all times, that separates me from my country of birth forever.

I need not mention to you, dear Mr. Browne, all the thousandfold intentionally cruel offences and pinpricks, that made our life unsupportable over there. No doubt you have often been told of them. …

If you had been living for years in surroundings where at every street corner you can see that it is preached to the people, to the man in the street, that they have to consider you as something of lower class, something despicable, when laws, infamous special laws have kept you and your wife and your children away from things that are open for everybody else, with the perverse aim of making your life unbearable, you come into a peculiar state of mind. Many may acquire an inferiority complex, but he who knows his own value, will react differently. A feeling of shame, of deep disgust, of contempt and hatred against the spirit of officially fostered infamy will take possession of him. And this will irrevocably separate him from everything in common with the creators of this new Creed, this new "Weltanschauung“ and their millions of followers. He would consider it a strong offence to be bracketed with them.

With such feelings I left my fatherland.

In January 1939, my grandmother (Rose) and their two daughters (Annelore, 17 and Dorothea, 13), travelling on the next voyage of the same ship, arrived in Melbourne.

Anne and Dorothea, as teenagers, recalled the journey as an adventure, as a welcome relief from the increasing difficulties the family was experiencing in Nazi Germany because of their Jewish background. They were also very much looking forward to being reunited with their father, seen here waiting for their ship to berth.

After a few days in a boarding house, the family moved into their newly built home at 90 Mentone Parade. Their first meal there was brought to them by their neighbours, the Edwards family, with whom they maintained a long friendship

After 18 months in the country, Erwin would write to Inspector Browne:

On the 19th August 1938 I landed in Melbourne. The entirely different atmosphere has made a deep and unforgettable impression upon me. Here, on foreign soil, where nobody knew me, friendly hands received me, I was welcomed in the kindest form that I could have expected. It was so easy here to make friends, real friends, full of encouragement, wishing to help me until I could find a new life.

All this was very impressive. The difference between the spirit that had forced me to leave my country of birth and the spirit which I found now in my country of adoption was so very great. I think I need not say where my heart is and my future, where I wish to have my home and the future of my children, where the only possible future is for all of us, from every angle of view, ideal and practical.

The family would remain at 90 Mentone Parade for many years. Erwin passed on in 1963; Rose in 1970. My aunt, Anne von Gizycki moved out of the house when it was sold and then demolished, but would stay in the area (Parkdale) until she moved into aged care shortly before her death in 2017. Mum continues to live in her nursing home in Caulfield South.

![Article from The Herald 25 April, 1939 [picture].](/sites/default/files/styles/article_inline_image/public/photos/Figure_1_The_Herald_25_April_1939_1.jpg?itok=lEOLEfiB)

![The Argus 26 April 1939 Page 31 [picture].](/sites/default/files/styles/article_inline_image/public/photos/Figure_2_The_Argus_26_April_1939_Page_31_0.jpg?itok=zi24wuSv)

![On board the Wuppertal from left: “Wuppertal” Captain Valentin Wenk, Dorothea, Anne [picture].](/sites/default/files/styles/article_inline_image/public/photos/On-board-the-Wuppertal_0.jpg?itok=pw_Fct3z)

![Waiting at wharf [picture].](/sites/default/files/styles/article_inline_image/public/photos/Figure_6_Waiting_at_wharf%5B1%5D_0.jpg?itok=ZZmq9WKK)

![Passenger list Wuppertal [picture].](/sites/default/files/styles/article_listing/public/photos/Figure_3_Passenger_list_Wuppertal.jpg?h=7ce95c12&itok=tKcNZlO4)

![First meal Mentone, from left: Anne, Dorothea, Rose, Erwin [picture].](/sites/default/files/styles/article_listing/public/photos/Figure_7_First_meal_Mentone.jpg?h=6d566689&itok=Z4ENGHXc)

![Anne at 90 on front page of Mordialloc Chelsea Leader [picture].](/sites/default/files/styles/article_listing/public/photos/Figure_8_Anne_at_90_Mordialloc_Chelsea_Leader.jpg?h=031b01a4&itok=AYjcEtf-)