Earning a Crust

“When George Thomas Allnutt was 21, he worked on the railway line, where he had a contract carting gravel with horse and drays. That gave him enough money to purchase 12 acres in Centre Dandenong Road in Cheltenham. That was in 1884. He lived by himself on his block until he had cleared the land, and then married. He and his wife started to breed Jersey cattle. They had Jersey cattle for many years, as the Jersey was a recognised breed, for its very rich milk. Then, over the next 25 years, he added other properties to it. He owned right back to where Mentone Racecourse was, right up to the corner of Warrigal Road and Cheltenham Roads. He was a vegetable grower, a dairy farmer, and later, a highly successful horse and cattle dealer," recalls Len Allnutt, George’s grandson. [2]

Committee of the Cheltenham and Moorabbin Show, November 8, 1913. Courtesy of Len Allnutt

Being independent and willing to work day and night to stay that way, helped early settlers such as George T. Allnutt, to make Kingston the thriving community it is today. What did people do for a living? How did these occupations come about? Where did the people who would shape the look and feel of the area come from? What opportunities did they have? What motivated them to follow their life path?

As soon as Real Estate Agents such as Birtchnell Brothers and Porter of Swanston Street, Melbourne, advertised country properties and agricultural land at the height of the boom in 1888, struggling farmers and even those who were not, were tempted to take up land in the Kingston area, where “the sale of hay promised to return 4 tons an acre" it was said. Birtchnell Brothers and Porter paid particular attention to the Carrum Swamp, where they recognised great value in the rich, decomposed soil, washed down hill for centuries." [3]

Alf Priestly recalls that his father shifted to Carrum from his farm on the Mallee. The government had made the allotments there too small, so they wanted half the farmers off the land, in order to increase the size of the holdings for the other half, he says. Despite the fact that the Government had offered him other allotments, Alf’s father chose to settle in Carrum. “Dad wanted to help run grandfather’s farm, and remain independent enough on one of his own," says Alf. “He shifted the whole lot. Horses, cattle, house, (the house was all dismantled), machinery; everything came down on one train. From the Mallee to Carrum! That was stock, everything! Poultry, the whole lot," Alf recalls with admiration. “The logistics of getting that together all within two days boggle the mind," he adds. “They had a helluva lot of get up and go! It had to be done … and no one was going to do that for them."[4]

Ken Smith’s father moved from Warracknabeal where he was a flour miller, to establish a poultry farm at Cheltenham in 1916. He paid £250 for three and a quarter acres, and built a house on it, mortgaging everything to the ES&A Bank, at Cheltenham, says Ken. [5] As there was no town water, they dug a sixty foot deep well, and bought a red windmill to pump water for their poultry. Ken says that’s how their property came to be named “The Red Mill Poultry Farm". They kept White Leghorns, Black Orpingtons, and Rhode Island Reds as well as a few ducks in the duck yard, Ken recalls. [6] The eggs were collected by a cartage firm called Coots, who took them to either Gippsland and Northern, or to Barrow Bros who were wholesalers. A cheque was sent to the poultry farmers when the eggs were sold to the retailers. Even though this came regularly, Ken says that his father never ever got out of the red. He always owed money to the bank. “A terrible amount," says Ken with great sympathy for his hardworking father. [7]

Seeking to make a better living, he turned to growing flowers in 1927. The idea for this, Ken says occurred to his father when he noticed a man in Glebe Avenue at Cheltenham growing poppies.

“You’d pick 50 poppies to a bunch and tie them up, burn the ends of the poppies with newspaper, and then dip them in cold water, and you might get 10 or 20 bunches every day, and take them in to Caulfield and finally Elwood, and hawk them for three pence a bunch. And that would bring a bit of money in, you see," says Ken. [8]

Flower growing became such a success that his father finally decided to get rid of the ‘chooks’ entirely in order to open a florist shop in Elwood. It paid money, he says. In fact, it made enough money for his father to be able to afford to buy the shop next door. Ken remembers that when he pulled his old shop down, a man called Watty Watson, once Mayor of St Kilda, built them a magnificent new shop with a residence up top in 1936. [9]

Another settler, Norman Charles Liddell had brought his family to Cheltenham from Mount Morgan in Queensland, to buy land in Farm Road. Norman Charles’s son, Alf Liddell remembers that it cost them about £1000, for a very nice home and eleven acres. They grew flowers, mainly carnations and Iceland poppies, says Alf. [10] Their Uncle Tom also grew delphiniums, but they were such a tender, precious plant, that the iron wheels of the lorry jerked off every head before it got to the corner of their stony, unmade road, he says with a chuckle.

The Liddell Family, 1910. Seated: Emma Liddell- nee Bloomfield (Left to Right). Standing, Tom Liddell, Alice Evelyn (Dolly) and Norman Charles Liddell. Courtesy of Alf Liddell.

Norman Charles Liddell’s daughter Sylvia Roberts recalls their journey to the market. “We used to go to market with Uncle Tom in the old lorry. The horse used to take us and would bring us back. There were tram plates on either side of the road and the horse used to get in these, and go right to the market. He wouldn’t have to be guided there and he wouldn’t have to be guided home. Uncle Tom would be asleep sitting up the back. This we’d start off at 11 o’clock at night and we’d get in there about 3 or 4 in the morning to sell our goods," she says.[11]

Children were expected to help with chores or the running of family enterprises, and there are amazing tales of their ability to shoulder major responsibilities at a very young age. There were eight children, Alf says, and the eldest four had pretty well left school by the time he started. His sister was taken out of school at about eleven years of age to help her mother at home. His dad took him out of school before he turned 14, and gave him the equivalent of $1.50 a week, and with the other hand took back $1.10 for living expenses, Alf says, with wry humour. [12]

“When we went down the paddock to hoe or weed or something, no boots were the thing," he recalls.

“We were only allowed to wear boots to school. There would be nettles there, but your feet would be so cold that you wouldn’t feel anything. My twin brother used to help. He was a little thin thing, and he used to cry, so I’d put him under a hedge and wrap his feet in my scarf, while I tried to do twice as much, so that old Tom wouldn’t know. Our feet would be like big heavy blocks. Then when the sun came out and your circulation started, they would itch, because of all the bites." [13]

Being multi-skilled was an asset then, as it is now. Success came to those who were able to see opportunities for growth, like George T. Allnutt, or turn a disaster in the marketplace into an advantage, as the Gartside Brothers were able to do. With his grandfather George T. Allnutt Len says, one thing led to another. While he was contracting on some big jobs on the roads, he also had horses working on them. “He started in a small way," says Len. “He was a great judge of a horse. He used to go all over country Victoria and to the Riverina, where they’d breed horses, and he’d buy horses, bring them down, and break them in." [14]

In those days there was no motor truck, and people had to depend on the horse for work and transport. They had different horses for different jobs, Len remembers. Bakers, butchers and milkmen had what were known as light delivery horses. Then there were heavy working horses, which would pull lorries filled with bricks, or cans of night soil, or work in the vegetable gardens and on the farms. He traded in all horses, says Len, but mainly working horses because he worked them himself. Once they were trained, he would sell them. [15]

Frank Baguley, who started the Flower Growers’ Association and still runs a thriving business, selling cut flowers and clean stock, in Heatherton, remembers the work opportunities created by the Gartside Brothers in Dingley. Charlie Gartside was a Member of Parliament, he recalls. He had four brothers and they started the canning factory before the war. They used to grow vegetables along with all the other market gardeners. When they realised that they couldn’t sell them to make a profit, they got the brilliant idea that if they could tin it, save it and sell it, they wouldn’t be selling the vegetables for nothing. The tin, save and sell solution of the Gartside Brothers was a boon to the local market gardening community. [16]

The Gartside Bros Cannery, 1932. Courtesy of Dingley Village and District Historical Society.

Frank recalls that he once worked for a man named Bob, who had cultivated just two acres of carrots in Dingley. Gartsides took the whole harvest of his carrots. All Bob had to do was pick them, and put them in bags. He didn’t even have to wash them! And after that, Frank says, old Bob built that new house up in Boundary Road for £350! [17]

Joe Souter, a successful market gardener, contractor, and a self-taught mechanical genius, explains that the Gartsides were engineers who started by dehydrating vegetables for the First World War troops, before they had their cannery. “They dehydrated vegetables, and then they went into pickles," he says. “They put them into bottles, big long bottles; square bottles in fact," he adds. They pickled onions, cauliflowers and made cauliflower mustard pickles. “Without a doubt," Joe says, “Gartsides had the best processed food in the whole of Australia." [18]

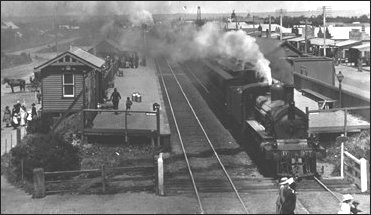

Service industries were needed to support the landowners. The skills of the ploughman were in demand. Wheelwrights and blacksmiths came to maintain horse drawn transport. And when Tommy Bent put through the train-line from Melbourne to Frankston bringing crowds of holiday-makers in its wake there was a need for stationmasters and mistresses, and cabbies for both horse drawn and motor vehicles, to carry people to their particular holiday destinations. [19]

In the era before tractors of course, Kath Kirkcaldy’s father was a wonderful ploughman. He used to plough the market gardens. In those days it was an acquired skill. Not everybody knew how to turn the furrows properly and also to get them straight says Kath, and her father was very good at what he did. [20]

Norm Stephens’ grandfather, Bill Stephens arrived in Carrum in the early 1900’s, and he became an all-rounder, combining the services of store-keeping, blacksmithing, timber selling and cattle dealing. He also became Mayor of the Borough of Carrum.[21] Bill employed a blacksmith, and his grandson Norm recalls that he and his father were always around horses watching the blacksmith shoeing them, or seeing his grandfather fitting steel tyres onto the jinkers they used to transport holiday-makers arriving at Carrum Station to destinations further down the bay. He used to play in there, he says, loading up the fire, heating up the iron and bending it. [22]

Although most people walked or rode horses and bikes everywhere, there were times when people needed to take a cab. Joy Telfer remembers she would get off the train when it was raining and get driven home by Mrs Dodd in her horse and jinker. Later, Mrs Dodd bought herself a car, and learnt to drive it, says Joy, and when she and her father came home on the train together, she would rather walk than ride with her. “I said to Dad, you go with Mrs. Dodd, Dad, you can go home with Mrs. Dodd, I’m walking!" [23] Perhaps suggesting that Mrs Dodd’s driving lacked something?

Chelsea Station about 1917, with Mrs Dodd’s cab to the left. Courtesy of Chelsea and District Historical Society.

Norm Stephens’ father operated as a cabby from the wood yard and blacksmith shop. There were five stables, and a loft, and the other part was a garage. It housed an old Chevrolet and a Ford, which were used as cabs after they finished with the horse-drawn ones, he recalls. [24]

The settlers in Kingston at the time of Federation had to be tough, flexible and inventive. Joe Souter regards the spirit of Australians as being somehow different. “I know and understand," he says, “because we lived in a country where you had to improvise, particularly on farms. You had to! Otherwise you took things to a blacksmith and waited for a week, or did it yourself. That’s the way it was. You had to think for yourself," he says. [25]

When he was President of the tennis club at Dingley, Joe was contracted by the Springvale Council to level the Dingley Reserve. He improvised a method of surveying the slanted surface of the reserve- (slanted so that it would drain he says)- so that the slant would be compensated for by the angle of the pegging. The councillors were astounded that his home-made method of surveying could be so accurate, says Joe’s wife, Betty, who along with Joe was on the committee for raising funds for the Dingley Reserve. [26]

George T. Allnutt’s grandson Len says that his grandfather was always having a go at making things, such as labour saving devices. He had a potato planter, which he did not patent, and he made the first tip truck from a T-model Ford chassis on which he built a tray body, when he was contracted to make the road from Frankston to Portsea. But the invention for which he is best known is the Invicta Butter Cutter. Len describes the Invicta Butter Cutter as standing on legs, with a series of wires crossways and vertically, which were brought down over the block of butter, to cut the 56 pounds into 112 and a half equal pieces with no waste. He patented it, says Len, and then a few years later he sold it to the Cherry’s, but he got the royalties for 30 years from it. Len recalls that there is one in the Dairy Museum at Phillip Island. [27]

The growing community needed supplies, and stores and shops in the area offered new opportunities of employment for women. Timber yards, such as Cauldwell’s of Mentone, not only supplied materials, but built houses as well. One of these was a house for William Black, the first settler in Chelsea. It’s still there today, on the corner of Swanpool Avenue and Black Street. His daughter Bertha Armstrong, remembers that later, her brother Sidney Black built the first shop in Chelsea for a Mr. Callaghan. ‘Why my father never opened one, I can’t imagine, as weekenders often came to my mother for something they had forgotten or run out of’ she writes. [28]

Edwin Thomas Deakin, a baker in Loch, South Gippsland, decided to settle in Carrum in 1901, and Miss Deakin describes her father’s beginnings as a baker:

‘My father proceeded to build a scotch oven with a furnace fed by wood. There was no electricity or piped water. So for the household needs, we had a water tank, and, for the doughs, water from a well. My father made the dough, baked the bread at night and delivered it by day from Frankston to Mordialloc along Pt. Nepean Road and over to Wells Road making a round trip with his horse and cart.’ [29]

Norm Stephens says that when his father left his Hardware Shop because he was unwilling to press for monies owed him by customers who enjoyed taking advantage of his gentle nature, he began working with Deakin’s Bakery. He and his dad, he says worked with Deakin’s until they finally sold out to the big firms, Hodders and Crowe at Black Rock, who in turn sold out to Sunicrust.

“I used to go with dad, in the old horse and cart days, delivering bread, of a Saturday morning," Norm remembers. “We used to leave about a quarter to five, I think. I would ride a pushbike, with a basket on the handlebars and deliver the bread up and down the streets of Chelsea. We’d walk down the bottom of Fowlers Avenue and deliver the bread to the houses down there. So dad would only have to come down, round, along and up."[30]

Surprisingly, there was a door-to-door delivery service of goods. Fresh bread; milk; meat; sometimes fish, and then the iceman called once a week with ice-blocks to keep things cool in the ice chest or old Coolgardie safe. Joy Telfer and her daughter Ann remember that Friday was always fish, because the fisherman called to the door. “They didn’t go shopping as we do nowadays because everybody delivered to the house. The grocer called and delivered … the store delivered; the milkman delivered and even into the late 40’s, the iceman delivered the blocks for the ice chest of their Coolgardie Safe on the back verandah," says Ann.[31]

Joyce Peterson remembers that there was a butcher, a Mr. Hewitt, who came up from Cheltenham once a week, with meat and ice in the cart. He had a piece of bracken to shoo the flies away. “When the cart was opened the meat nearly walked out to me," she says. There was also Aldridge the baker; there was a fruit man and the Co-op grocer, who used to come round one day to get the order and deliver the next, she recalls.[32]

Publicans, hoteliers and innkeepers were attracted to the district to provide hospice and a place for entertainment and relaxation for visitors and locals. Men only of course, as women were not seen in such establishments except in the course of duty as cleaners or barmaids. Joy Telfer recalls that the women used to sit out around the brick wall shelling their peas for tea, and the husbands would be in the pubs, because the ladies weren’t allowed in. [33]

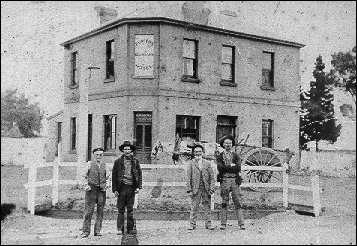

The general store Sidney Black built at Carrum for Mr. Callaghan was sold to a Mr. Gill, who in turn sold out to a Mrs. Duncan. She held a Commonwealth wine licence for the small wine saloon on the south side of that building from 1908.[34] So not all publicans were men. There seem to have been at least two women publicans known to Alf Liddell. He recalls that Mary Porter, a Methodist, actually built the Boundary Road Pub at the corner of East Boundary Road and Centre Road. “Nobody was allowed to talk about it," he says. “She was forbidden fruit. She made herself forbidden fruit. A nice pub, when she built it. She didn’t muck around. No half measures. It’s still there," says Alf. [35] Then there was the popular Cheltenham or Keighran’s Hotel from which Cheltenham got its name. It was a hub of action, and the publican, Keighran himself is the subject of many a great yarn told by Len Allnutt. [36]

Porter’s Boundary Hotel, 1905.

As the settlement became established land became more attractive, and real estate agents took up residence. The community built churches and schools helped by benefactors such as the Allnutts, Attenboroughs and Gartsides. Clergy and undertaker served the spiritual needs of the community and teachers took up the challenge of educating children.

Banks were there to offer credit and managers at times risked their personal money to give worthwhile people a chance to survive in hard times. Joe Souter recalls that his father wanted to buy a horse, and went to one of the banks saying that he needed to borrow eight pounds to buy it. When the bank manager asked him what collateral he had, his father had said, ‘My face!’ “The manager looked at him", Joe goes on with the story. “ ‘Oh!’ He says. ‘I don’t know,’ he says, ‘But I tell you what’, he says, “I will lend you the eight pound, but if you don’t pay me, I’ll lose that eight pounds with the Bank." [37]

And of course, the community demanded doctors, midwives and nurses, to deal with their medical problems. Ken Smith recalls that a Dr Johnstone had a medical centre just south of where the Cheltenham School is now. On one occasion, he was going to Sunday school with Kenny Butterworth, and they were misbehaving. Young Butterworth dropped half a brick on Ken’s head and cut it right open. He had no sympathy from his father, he recalls, who merely sent him bleeding to Dr Johnstone. “Dr Johnstone said, ‘I won’t stitch it up, because the stitch marks will stay’ so he only put plaster across," reports Ken still wincing at the thought. [38]

Women were as capable and resourceful in their own way as the men, working in the fields when necessary. Frank Baguley’s wife helped him throughout the mean, lean and good times. “My wife helped me one helluva lot in the early days after we were married. She worked with me, all the times, never faltered. She used to pick flowers with two children on her back, and helped him to clear the block, sawing through trees some of which were five feet across. “She helped me do that," he says.[39]

Len Allnutt recalls that many women were in domestic service. They were employed in shops, perhaps as bookkeepers. Estate Agents always had girls in their offices as secretaries. And then of course there were the teaching and nursing professions. A lot of country girls would take on nursing or teaching, he observes. [40] The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum (MBA) established in Cheltenham offered employment for administrative, domestic and nursing staff during this time. Len recalls this interesting story about the MBA.

“Actually," Len says, “How the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum came to be there, was because of Tommy Bent. The home was at North Melbourne. It was overflowing and they knew they had to get somewhere else. When Tommy Bent who represented this area, obtained the 300 odd acres at Cheltenham the press attacked him.[41] There was a great howl, he ought to be gaoled, and all the rest of it. There was a great furore. He bought it to make employment in his own constituency. Before they got the land cleared and the buildings up, he had died. I think it was round about 1903–1904 when he got the land, and the Benev. didn’t finally open here until 1910. That’s how it came to be out here, from North Melbourne, because Tommy Bent bought the land. He was the instigator," Len maintains.[42]

Many nurses were needed at the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum. Courtesy of Len and Dorothy Allnutt

And of course, for the final journey, there was a need for the specialised skill of the undertaker. W.D. Rose was an undertaking firm established in the district in the 1880s. It was a family concern. Len Allnutt’s family had a long friendship with the Roses lasting to this day. “There was a fellow in our grade at school who lived near here, who became a gravedigger, and he said to me that in all the 40 years he had been at the Cheltenham Cemetery, no undertaker had ever said a word against Roses. “That’s the name they bear," says Len with pride. [43]

Those who were in a better position than others did not shirk their duty of care to the community. Ken Smith remembers that the Rose Family spent a lot of money on looking after people. They did it quietly, he says. The front door was always open, and inside, there were all classes of people, from top to bottom in their lounge room having a chat. This was characteristic of the times, he fondly recalls.[44]

There was a great deal of unpaid work done by men and women in those early days. Families not only worked hard for a crust. They freely and cheerfully contributed of their time, money and talent to provide transport, entertainment, and facilities, and also to organise committees and events to showcase the achievements of their beloved communities.

Len Allnutt says that in his father’s day, people gave their time freely. They would have been offended if anybody had offered them any pay for what they did, he maintains. “They would put their own money into things, and if there were an appeal they would be the first to throw in money." They tried to help the sporting clubs, and all the other things in the district." He recalls with approval. [45]

Footnotes