Southland Expands Across Nepean Highway

In 1991 Westfield Development Limited announced its plan to extend the Southland shopping complex across Nepean Highway, Cheltenham. [1] This location, originally part of the land purchased by Charles Smith, passed through various owners including Joseph Lucas Australia Limited and the Cheltenham Community Market before becoming part of a proposed $200 million development project. It was reported in the Weekend Australian that the site passed from the Community Market to its new owners for $7,000,000. [2]

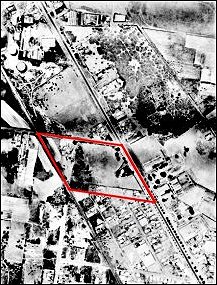

Aerial photograph showing site of Westfield extension in 1945.

The history of the site reveals some very good deals being made by investors. [3] Commencing in 1852 Charles Smith, a farmer, paid £118 16s at auction for a one hundred and thirteen acre block in the parish of Moorabbin. Less than a year later, on January 12, 1853, he sold a ten-acre section of it to Charles Everall, a gardener of the parish of St Kilda, for sixty pounds sterling. This portion was on the southern corner of what is now Bay Road and Nepean Highway and stretching down towards what was later to be the Mordialloc railway line. Everall only held the land for six months before selling it to Peter Le Lievre for ninety pounds. Another handsome profit for a short-term investment!

Peter Le Lievre sold the land on July 24, 1860 for one hundred and six pounds to John Brownridge who mortgaged the land for one hundred twenty five pounds ten shilling to John Arnold Macarthy on March 17, 1862. Macarthy was the man who became President of the Moorabbin Roads Board in 1869 and first president of the newly created Shire of Moorabbin in 1871. In 1876 the mortgage was discharged and the ten acres was sold to Walter Stevenson for one thousand and twenty pounds reflecting the escalating prices being paid for land at the time.

In 1882, the year after the construction of the Mordialloc railway line on the western boundary of the property, the land was purchased by Thomas Bane of La Trobe Street, West Melbourne. Bane was the hotelkeeper of the Duke of Kent. When he died on January 6, 1891 the land became the responsibility of the National Trustees Executors. By this time the market for real estate had disappeared, nevertheless the probate papers indicated the property was valued at £2500. [4] Property values throughout Melbourne had fallen and many of the land companies, who had invested in acreage and allotments with the intention of making large profits on resale, had collapsed and declared bankrupt to the consternation of their shareholders and depositors.

On January 27, 1909 the ownership of the land was transferred to Thomas’s wife Anne and their five children Cecilia, Lily, Ignatius, Joseph and Francis James Bane. With the death of Francis and Ann the ownership of the land fell to Cecilia, Lily, Jospeh and Ignatius. They were the owners on December 21, 1926.[5] The descendants of Thomas Bane continued to hold the land until May 23, 1947 when the property was sold to Parson Pty Ltd. It was that company who sold the land to Joseph Lucas on June 2, 1950.

The Lucas factory 1995. From the Leader Collection.

The front-page headline of the Moorabbin Standard of June 1982 announced that the Lucas site was for sale. [6] It was in the same newspaper in January of the following year that the new owners declared their intention of building a market. [7] Despite great predictions for its future, the Cheltenham Market failed to become the financial success expected and as a consequence an official receiver was appointed by the Hong Kong Bank and moves to sell the market by tender commenced in 1990. [8] By November 1992 the new purchaser announced the plan to extend Southland on the former market site with a bridge straddling Nepean Highway. [9]

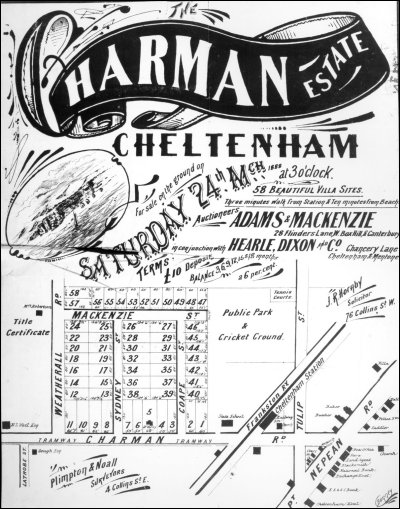

An estate agent’s poster advertising the sale of land on the Charman Estate in 1888 included a sketch map of Cheltenham. The map shows the existence of a villa on the Bane land. Thomas Bane’s probate papers indicate the house was brick and had six rooms. The outhouses were wooden. When the house was built is not known but it was demolished in the 1950’s when the Lucas factory was constructed. At the time of the house’s destruction it was derelict and had been so for many years. It is not known if Thomas Bane and his family lived in the house but two of his daughters resided there under the care of Patrick and Maria Hayes for six years from January 7, 1885 until the death of their father. Thomas Bane believed the surroundings, example and influence of the Duke of Kent hotel in Latrobe Street, Melbourne was prejudicial to the rearing of his two daughters, Cecilia and Lily. In addition to caring for two of his children Patrick Hayes was engaged by Thomas Bane to look after the property. For completing this task Bane paid Hayes the wage of one pound per week and allowed him to live in the house rent free. [10]

Charman Estate poster showing the location of the Bane villa in the bottom right corner, 1888.

The last people to live in the house were the family of Charles Bert Whitehead, a greengrocer who rented the property. Connie (Kathleen) Town, Bert’s eldest daughter recalled living in the house after the First World War. “The house was in decay. The rain got in in different spots and there were possums in the roof. At night they used to run across the roof and the next time you would see them they would be up in the trees in the moonlight." [11]

“Once it must have been a beautiful brick house with a slate roof. Before we lived there it has been occupied by Miss Reynolds, a school teacher. There were several bedrooms. I think it was a house that had maids. They had bells, old fashion bells near the kitchen to call the maids. There was a room off the kitchen, which I think must have been the maids’ room. There was a veranda around the front of the house and down the side. There was no bathroom. We used to have a bath in the washhouse as we called it in those days. It was further down the backyard. There wasn’t even a bath there. I think we used to bathe in the wash trough. There was a copper there and two troughs but no bath. The toilet was down the back of the yard together with a well. The well had a pump but it was rarely used and only for the garden".

“At the front of part of the property there was a Hawthorn hedge with its prickles and red berries. On the corner of Bay Road and Point Nepean Road there were several very tall pine trees. Towards the back near the railway line there was a hill of bracken fern and some wattle trees. At the front of the house there was garden containing many jonquil bulbs that continued to flower each Spring for many years long after we left. There was a circular drive with a fine oak tree at one of the front gates. This tree was left there even after Lucas factory was built. I can also remember a large cork tree that was in the front but the garden, which had originally been formally laid out, was like the house neglected and overgrown when the we took possession."

Aerial photograph showing the Bane residence and the pine trees, 1945.

The land surrounding the house had been used as a market garden but had been allowed to return to natural pasture before the Whiteheads took occupancy. They grazed seven cows and a number of heifers there to provide milk and a small income to the family. They also kept about two dozen hens for eggs. After the Whiteheads left, the land was used by a local dairy farmer to graze his cows during the day.

With the purchase of the land on May 23, 1947 by Parsons Pty Ltd, the expectation was that the company would build a factory to manufacture its breakfast cereals, custard powder and other cooking products. [12] This expectation was not fulfilled. Until the transfer of the land title, which occurred on June 2, 1950, the land remained unimproved pasture with sections covered with bracken and the occasional wattle tree. Joseph Lucas, an Australian subsidiary of an English company purchased this property together with some adjoining land to gain ownership of “sixteen acres one rood eighteen perches and three tenths of a perch or thereabouts" of the one hundred and thirteen acres originally granted to Charles Smith almost one hundred years previously.

Joseph Lucas, first registered in Australia in 1929 decided in 1951 to commence manufacturing its various products locally. They chose to use the Cheltenham property as the site for their £4,500,000 development. With extensions in 1956 the operation had 240,440 square feet and employed 1700 workers producing electrical and automotive equipment, starter motors, batteries, accessories such as horns, mirrors, wipers and screen washers, auxiliary lamps, brakes and shock absorbers. [13]

Principal buildings on the site in 1984 were the main factory building of approximately 25,300 square metres, the canteen building of approximately 1,860 square metres and the administration block of approximately 1,575 square metres. Other buildings include two houses, workshop areas, storage buildings and an effluent treatment plant. [14]

By 1982 the local motor industry was languishing. This was due; it was claimed, to the flood of imported vehicles and parts and the fragmentation of the national automotive market. Three local politicians were angry with the Federal government, “in forcing the car parts industry to the wall." [15] One hundred and fifty workers were retrenched by Lucas in June 1982 and just on one hundred workers in Moorabbin automotive parts factories suffered the same fate the following month. Further retrenchments occurred at Lucas in February of the following year and the company announced it would cease manufacturing certain products and shift its operation to a new factory. Subsequently it merged with Hella-Australia and placed the Cheltenham factory site on the market.

In January 1984 Twenty Ninth Trite Nominees Pty Ltd entered into a contract with Lucas Industries (Australia) Ltd to purchase that company’s site on the corner of Nepean Highway and Bay Road, Cheltenham. Twenty Ninth Trite Nominees applied to the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works in January 1984 to rezone the factory site from a light industrial zone to an appropriate zone to facilitate the establishment of a retail market and other associated uses. A raft of consultants was employed by the company to advise on various aspects of their proposal to re develop the site as a community market: architectural, site services, town planning, landscaping, traffic and parking. Their conclusions were presented in a report entitled, “A Proposal to Redevelop the Lucas Site Cheltenham Victoria."

The plan was to develop a market which included a food hall for the sale of butchers meat, poultry, fruit and vegetables, a general area for the sale of clothes, footwear and household items, a food court for take away items, a nursery area for sale of plants and related gardening items, craft stores, furniture, electrical appliances and a mini food market selling groceries. Provision was to be made for the parking of 900 cars in landscaped areas.

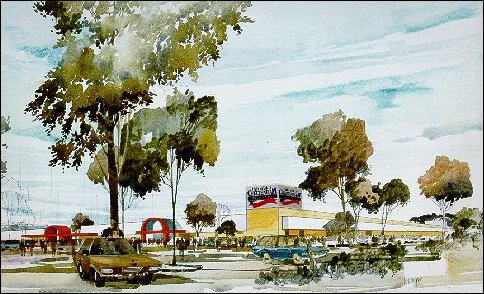

Architectural perspective of the proposed Cheltenham Market 1984.

The submission argued that markets were particularly significant to Melbourne pointing to major markets founded last century - Queen Victorian market 1859, Prahran Market 1864 South Melbourne Market 1866. “Their importance to Victorians is unquestionable. Markets have a regional drawing power and provide a focus of community activities." [16] Market research suggested that a significant proportion of the community were interested in market shopping and more than 156,000 residents were not effectively being served by a retail market. On the basis of initial enquires the developers believed there was strong interest from small businessmen in taking up stalls.

In November 1983, the Moorabbin Council gave support to the project but it was not until May 1985 that it was announced that the appropriate approval had been given by the State government. This was given after the Board of Works rezoned the site and a favourable finding was given by an independent investigative panel appointed by Mr Walker, Minister of Planning.

Despite initial enthusiasm from some people, the market failed to attract and maintain the customer support envisaged in the original development brief. With falling trade, by March 1990 some stall holders were falling behind in their rent payments and as a result some had been denied access to their stalls. [17] James Romanis, the agent acting for the market was reported as saying, “The position of the ongoing nature of the market is very clouded" pointing to the lack of financial viability. An editorial comment in the Moorabbin Standard reported the situation more colourfully, “The stench of defeat mingles with the market odors of fresh fish and pungent cheeses." [18] Blame for the demise was directed to the early tenants who charged too much for their goods to attract customers, to the Moorabbin Council for not permitting Sunday trading, and to the rivalry and competition of local shopping centres.

There were plans to revamp the operation of the market, to advertise, to attract new stallholders and to trade on Sunday all actions, which encouraged a more optimistic outlook of the current tenants. [19] Their optimism soon faded. James Romanis and Co was appointed as official receiver for the Hong Kong Bank and within months had moved to sell the market by tender. [20]

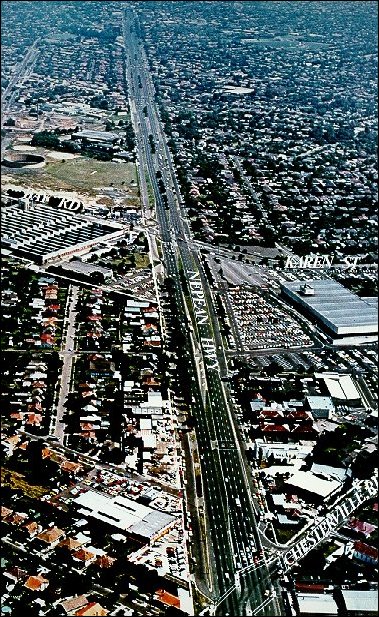

Aerial photograph showing Lucas factory and Southland in 1984.

The Moorabbin Council at a meeting in February 1991 resolved in principle to pursue redevelopment of the ‘Market Site’ and at a subsequent meeting of councillors, council officers and representatives of Westfield two proposals were discussed. [21] One involved the construction of a bridge and the other a tunnel to join the two properties now owned by Westfield. It was in December 1991 that Westfield Developments revealed its plan concerning the extension of Southland to the ‘Market Site’. The proposal was to construct a two level building housing a food court, department stores, specialty shops and a ten-storey office tower on the market site. [22] The new property was to be linked by a bridge across Nepean Highway. Just as the Cheltenham Market proposal generated a negative response with some groups when plans were announced, the Westfield proposal to extend the shopping centre across Nepean Highway to the market site was not greeted with enthusiasm by all people. The concept of a retail bridge linking the two sites generated some hostility. This was a relative new concept in Australia. In addition to the bridge, many feared the impact of this giant shopping complex on the smaller shopping centres in the district and predicted heavy financial losses for small businesses. [23] Concern was also expressed about the anticipated loss of local work opportunities. Nevertheless the construction of the complex, with modifications, went ahead.

Footnotes

- Moorabbin Standard, December 18. 1991.

- Weekend Australian, January 18, 1992.

- Certificates of Title, Title Office Melbourne.

- Probate Papers - Public Records Office.

- The last surviving children of Thomas Bane were Lily who died at Toorak aged 64 in 1946 and Cecilia who died at Camberwell in 1965 aged 85.

- Moorabbin Standard, June 16, 1982.

- Certificate of Title shows the transfer of land from Joseph Lucas to the Cheltenham Community Market occurred on April 10, 1985.

- Moorabbin Standard, June 13, 1990.

- Moorabbin Standard, November 10, 1992.

- Mrs Anne Bane affidavit - Public Records Office Files .

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Kathleen Town, January 1988.

- Several large companies were considering establishing factories in the Municipality of Moorabbin at that time. H.J.Heinz Pty Ltd was exploring the possibility of building ‘a modern factory in a parkland setting’. Moorabbin News, May 15, 1947.

- Moorabbin News , December 15, 1960.

- A Proposal to redevelop the Lucas Site Cheltenham Victoria. Page U3.

- Moorabbin Standard, February 23, 1983. Mr Graham Ihlein, MLA for Sandringham; Mr Lewis Kent MHR for Hotham; and Mr David Charles, MHR for Isaccs.

- A Proposal to redevelop the Lucas Site Cheltenham Victoria. Page U9.

- Moorabbin Standard, March 21, 1990.

- Moorabbin Standard, Ibid.

- Moorabbin Standard, June 13, 1990.

- The Herald, March 6, 1990 contained advertisement calling for tenders. Time for submissions closed on April 12, 1990.

- Crs M Trist, B Flavell, R Brownlees, B Neve and N Hamilton were the councillors present at the meeting held on June 6, 1991. The Mayor, Cr N Bennett was an apology. City of Moorabbin File: Redevelopment of Westfield and Cheltenham Market.

- Moorabbin Standard, December 18, 1991.

- Moorabbin Standard, February 26, 1992.