Off To The War In South Africa 1899-1902

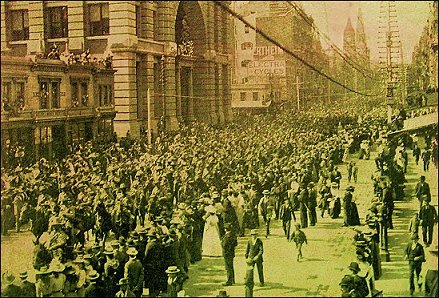

Marching down Collins Street, Melbourne before departure for South Africa.

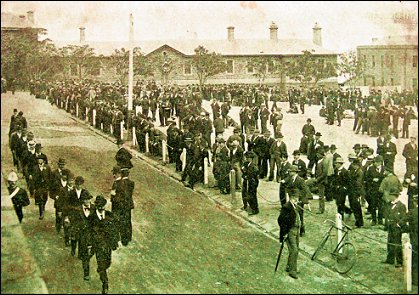

The colony of Victoria offered to provide volunteers to support Britain’s campaign against the Boers in South Africa and by the end of September 1899, before hostilities had been declared, 1153 men had volunteered from Victoria. [1] Cheltenham members of the Victorian Rangers, G Company, were amongst this number. Other residents of the district also volunteered, some of these men being selected to join one of the several contingents leaving Melbourne. The first sailed on October 22, 1899, the second contingent quickly followed on January 13, 1900, with the third contingent known as the ‘Bushmen’s Contingent’ departing on March 10 in the same year. The ‘Imperial Contingent’, the fourth group, sailed from Melbourne for South Africa on May 1, 1900. This contingent was given the title ‘Imperial’ because the British Government accepted the responsibility for paying allowances and pensions. [2] The criteria used in selecting the members of the contingents included physical and medical fitness, ability to shot and ride and marital state. Single men were preferred. [3]

Men enlisting at Victoria Barracks to join the Fourth ‘Imperial’ Contingent.

The fifth contingent under the command of Colonel Otter sailed from Melbourne on February 15, 1901 while the final three contingents were raised after Federation and members were part of the Australian Commonwealth Horse. Their departure dates were February 12, 1902, March 26, 1902 and May 19, 1902 meaning that the last group arrived in South Africa after the cessation of hostilities on May 31, 1902.

Some Victorians joined other units in South Africa. Lieutenant Murray from Sandringham was with the Wiltshire Regiment while F W Symonds signed on with the Durban Light Infantry [4] Private R G Keys, the son of George Keys of Cheltenham, joined Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts and John Foster, also of Cheltenham enlisted in the Kaffrarian Mounted Rifles, a force primarily made up of Australians.[5] Murphy was with the Imperial Light Horse.

Men joining the Victorian contingents volunteered for twelve months’ service but many continued to serve beyond this period of time in British Imperial units or later Australian contingents. Albert Fisher of Cheltenham, originally with the First Contingent later served with the Orange River colony’s Provisional Mounted Police, then the South African Constabulary, and later still the Canterbury Division of the New Zealand Garrison Artillery.[6] Towards the end of their time in South Africa members of the Third Contingent were invited to join the Royal Artillery and seven men responded. [7] Tom Germaine, son of Mentone’s publican, was one of these. He comments in a letter home, “I have been promoted to sergeant. Not so bad for a Mentone youngster, is it?” [8] William McKnight joined the Fifth Contingent with the rank of major but he was originally a member of the Third Contingent before joining his former commanding officer in the Victorian Rangers, Colonel Otter. When it came time for members of the Imperial Contingent to return to Melbourne, they were encouraged to remain in South Africa and join other military units. Promotion was an incentive as those staying obtained promotion of at least one rank; sergeants became lieutenants and troopers became sergeants. [9] After making his own way to South Africa Lt H Kessell, a member of the Cheltenham Company of the Victorian Rangers, joined the Fifth Contingent in June 1901. Later he joined the 6th Battalion Australian Commonwealth Horse (Eighth Victorian Contingent) where he served as a troop leader.

There were many more from Moorabbin district at this war. Will Christie, George Stayner and Tom Matson were members of the First Contingent. William George Rigg and William Daff were members of the second and although William McKnight volunteered for both the first and second contingents he was not selected.[10] He had to wait for the Third Contingent before gaining his opportunity to join the action in South Africa. Farrier Sergeant P Ockenden and William Gillespie were also members of the Third Contingent. James Collins left with the Fifth Contingent only to die at Wilmansrust a few months later, one of at least four volunteers from the Moorabbin District to lose their lives. [11] Many men sent letters home from South Africa to their friends and relations and it is these letters or extracts of them published in local papers that provide the substance of this report.

These men together with their comrades were farewelled, prior to departure for South Africa , by friends and colleagues, presented with gifts and urged to return safely. Tom Matson was presented with a gold watch subscribed for by the residents of East Brighton while George Stayner and Albert Fisher each received a silver match box suitably engraved together with field glasses. Tom Germaine and E M Caughey with the Imperial Contingent were farewelled at the Mentone Hotel where Tom’s father as publican, hosted the farewell where they were both given a pair of field glasses. Tom also received a leather belt containing sovereigns from a well wisher. [12].. James McCormick, Dr Scantlebury’s groom for eight years and a popular captain of a local football team, also received a pair of field glasses as a gift from members of the local community. His farewell held in the Exchange Hotel Cheltenham was attended by about sixty people, and was followed up with a dance in the Mechanics’ Hall lasting from 10 to 12 at night. [13]

A community meeting at Cheltenham rejected the idea of presenting Captain McKnight with a horse as the animal would become the property of the government. Instead he was given an illuminated address, signed by representatives of organisations with which he was associated, together with a purse of 47 sovereigns. The Market Gardeners’ Picnic Committee, with which Captain McKnight had been associated for seventeen years, gave him a cheque of £10 and at the same meeting Farrier Sergeant Ockenden received a purse of seven sovereigns. [14] Cr Penny, President of Moorabbin Shire, apologised for the small amount but “they had heard only within the last few days of Sergeant Ockenden’s connection with the contingent.” [15]

Leaving the camp at Langwarrin where they had been in training for their operations against the Boer, the troops travelled through Chelsea, Mordialloc, Mentone, Cheltenham and Brighton on their way via the city to their embarkment point at Port Melbourne. The first contingent received an enthusiastic send off all along the route.

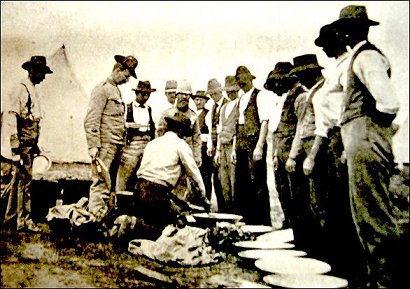

At the Langwarrin Camp.

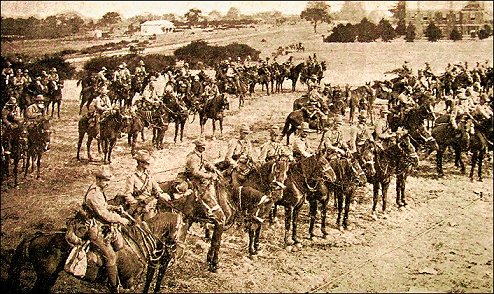

The third contingent on arrival at Cheltenham was “scarcely recognisable” as members were covered with dust from“ head to foot” raised by the hoofs of the horses proceeding along dry and dusty roads. [16] On arrival the troopers were greeted by buildings decorated with flags and bunting, and three triumphal arches. One was opposite Keighran’s hotel bearing the words, ‘Good Luck’, the second was opposite the Post Office reading ‘God Bless Our Queen’, while the third, above the Protestant Alliance Hall, carried the message ‘God Speed’. The Brighton Southern Cross reported the arches were well made although the second with the letters VR in the centre formed with flowers was exceptional. [17] Several hundred people had travelled from Melbourne and the surrounding districts to farewell them from their last stop before they embarked at Port Melbourne on the SS Euryalus. People said that the demands on Keighran’s Cheltenham Hotel were so great that the publican was forced to water the whisky so that customer demands could be met.

A reporter from the Cheltenham Leader described the cheering which greeted the troops: “One or two of the horses startled by the noise or perhaps by the coloured flags, bolted from the ranks and sent the crowd shrieking on to the footpath. One horse, the same wicked little black fellow that has caused no end of bother in the camp, suddenly commenced to buck, and the rider, after sticking resolutely to the saddle for a few moments, was thrown on to the hard road. Fortunately, he sustained no injury and was soon mounted again.” [18]

Cr E Penny, the President of the Moorabbin Shire spoke a few words of welcome and Colonel Otter responded briefly before indicating the men were hungry and the horses needed ‘their grub’. [19] The President was there in his official capacity but only after lengthy discussion at a Council meeting on the merits of erecting arches and the need to spend £5. Cr Burgess said the “contingent had not done anything to cause rejoicing” and he did not believe in “frittering away £5 on an empty show”. [20] On the other hand Cr Thomas Bent said the contingent were “loyally responding to a call of duty and there would be reasons for sorrow if the residents did not publicly manifest their appreciation of their action.” Bent’s colleague Cr Mills thought the locals would give the troops a “right royal welcome” but thought a good dinner, after a dry march, without intoxicating drinks, would be more appreciated than a triumphal arch. Finally it was left to the President to determine how he would spend the £5. He indicated it would not be for an arch! Nevertheless three arches were built across the main road.

The men were billeted in the Rangers’ Orderly Room and the Mechanics’ Institute with the horses being picketed in a neighbouring paddock. The next morning the contingent left twenty minutes early as Colonel Otter remarked “military law does not countenance unpunctuality in arriving at the end of the journey.” [21] As they left, “boys and girls and young maidens threw showers of blooms at the men as they rode by, until the sombre khaki uniforms became gay with bright colours and men held flowers in their hands while waving adieus.” The reporter went on to write, “This was too much for Captain Dobbin, who left his place at the head of the column. ‘Put those flowers away’, he commanded. ‘You’re soldiers now, not children’.”

The Third Contingent Parades in Readiness to leave Cheltenham.

Triumphal arches, bunting and flags were again features of the farewell organised for the Fourth or Imperial Contingent. But this time the centre of activity was Mentone. A daily paper reported great jealousy existed between the Cheltenham community and the Mentone community regarding the opportunity to billet the troops and their horses, but a report in the Moorabbin News contradicted this view noting that Cheltenham didn’t even apply for the privilege of bivouacking the 700 men. [22] A Department of Defence official had noted the accommodation available at Cheltenham was scarcely sufficient and suggested the use of the skating rink at Mentone.

Again the President of the Shire, Cr Penny, welcomed the troops to the Shire, and Major Clarke, responded.[23] Mentone people were good hosts despite the contingent’s late arrival. Nevertheless there was some sensitivity amongst some members of the community as to how the troops might behave themselves. Initially the owners of the skating rink declined to bivouac the troops but with the agreement of Crs Smith and Storey to act as guarantees for repairs to any damage done by the contingent they reversed their decision. [24] The troops were well treated and some were observed to be walking their ‘sisters and cousins’ in the grounds and streets of Mentone. [25] One soldier was reported to the police for firing three shots from a revolver at three gentlemen, one of whom was grazed in the lower abdomen during the incident. Constable Canty failed to find the culprit and Colonel Kelly promised to investigate the matter further but nothing eventuated. [26] Another incident reported in the local press was where a “commando of Imperial Bushmen commandeered five bottles of laager beer from a grocer’s cart on the Nepean Road, the driver being compelled to gallop through their ranks in order that all his customers should not be disappointed.” [27]

In general the men were described as a fine sturdy group, resourceful, determined and unflinching. The same writer was less impressed by the officers noting the comments of a member of the contingent; “We are all supposed to be riders, good shots, and trackers but some of the officers are not fit to track their ballroom partner to her seat in the conservatory, or ride a goat down the tradesmen’s entrance of their aristocratic residence.” [28] During their stay in Mentone officers took advantage of the superior accommodation provided by Como House and the Mentone Hotel. Mrs Pearson entertained 19 officers at Como House while 12 were with Mr J Germaine at the hotel on Beach Road.

After reaching Port Melbourne the troops embarked for the voyage to Capetown in South Africa. A member of the First Contingent and a correspondent to the Brighton South Cross wrote of a fairly calm trip from Albany to the Cape on the Medic except for a few rough hours towards the end of the voyage. Corporal Daniel wrote that the storm caught them about 5 o’clock in morning and gave them a rough time. “We had to stand to our horses and the seas were breaking over so heavily that sometimes you would see nothing but water, and it would wash across the deck up to our knees. Our over coats were no good, for we were soon wet through. We would wring the water from our shirts.” [29]

The Brighton Southern Cross correspondent was sorry to leave the Medic “although the food was none of the best.” George Stayner referred to the rough and ready style of serving meals on the ship and was not complimentary regarding the supply of pannikins and other utensils. The soldiers were required to undertake light drill on board but there was plenty of spare time. One of the activities involved shooting at floating barrels that were thrown overboard. “This was practised every second or third day and some very good shooting was done up to 1,300 yards,” the newspaper reported. Medic arrived in Capetown on November 28, 1899 and it was there the First Contingent disembarked. [30]

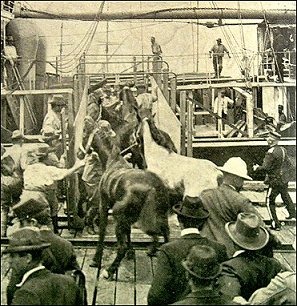

Corporal Daniel of Oakleigh described his first washing day during the voyage on board the Medic. “It was a pretty big wash - cotton tunic and trousers, two shirts, two pairs socks, some handkerchiefs, underpants, towel, &c. I managed to get some hot water, but only had common yellow soap but they were clean, and that’s good enough.” Another task on board ship was to look after the horses. “They get a lot of handling, as we have to climb all over them to groom and muck out, when we get in behind with a shovel and basket and crawl along his back and pass the full basket over his head to our mates, as there is not spare room.” [31] Despite the cramped conditions the horses arrived in South Africa in “first rate condition. Only one horse died during the voyage.” [32]

Loading the horses on Euryalus for their journey to South Africa.

On arrival in Capetown a Brighton Southern Cross correspondent reported his surprise at seeing so many “colored people” there. “About three out of every four you meet are darkies,” he claimed. He went on to describe the narrow macadamised roads and streets through which the trains ran, disturbing their horses. Most carts were two wheelers pulled by mules. Four wheelers were rarely seen. This was because a toll was placed on carts according to the number of wheels used in their construction. He thought Table Mountain overshadowing Capetown was very pretty, especially in the early morning when the mist had lifted. “Beyond Capetown the country was stony with poor soil covered with eighteen inch high patchy scrub. Protea was very common for the first 100 miles and there was some beautiful native heaths but grass was scarce.” [33]

Farrier Sergeant Ockenden and Private Gillespie of the Third Contingent wrote about the voyage on the SS Euryalus to their friends at home. The first twenty four hours were fine but after that, as Ockenden wrote, “you could not kick them out of your way; they were lying about in all directions.” Gillespie explained, “Bushmen, you know, are not sailors, and with their usual generosity they often parted with the greater portion of their meals, so that the little fish might be fed. However, we soon got over that lot.”[34] But no sooner had they recovered from their seasickness than the vaccinations commenced. The result was a sore arm for a couple of days. [35] George Stayner of the First Contingent also commented on the vaccinations. He received the needle twice on the way to Africa but both attempts failed. The program of inoculation was instituted because of the presence of small pox in South Africa

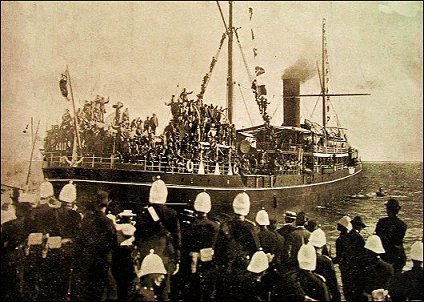

Departure of the Euryalus from Melbourne.

Sergeant Ockenden described his daily routine on board the Euryalus He would rise each morning at a quarter to five, have a cup of coffee and a biscuit and then attend to the horses. Seven o’clock was breakfast time. After breakfast the sick horses took all his attention and this continued until eleven o’clock when he was freed from duties until three o’clock in the afternoon, at which time the routine was repeated. During free time there were plenty of amusements on board the ship; tugs-of-war, obstacle races, magic lantern shows and revolver practice. Ockenden wrote of the revolver practice where a kerosene tin was hung from the yardarm. He was obviously successful in this activity as Captain McKnight wrote in one of his letters that Ockenden was the best shot amongst the sergeants, securing a score of 10 hits out of 12 on one occasion. [36]

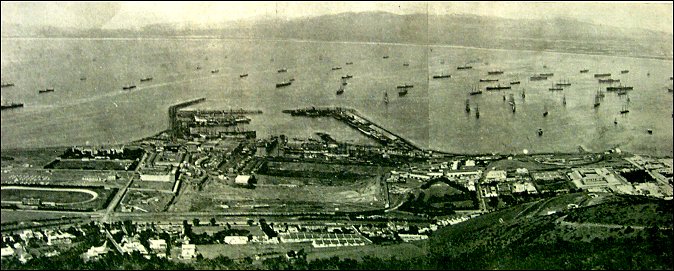

The Third Contingent arrived in Capetown on April 3, 1900. Ockenden reported home that going up the harbour at Capetown was a lovely sight, “the scenery being beautiful”. There were about 123 vessels anchored in the bay and out of that number 101 had brought troops, horses and mules. The troops were not allowed to disembark, remaining on board for several days before sailing on to Beira in Portuguese East Africa where the scenery was not as attractive being, “all sand and scrub” according to McKnight. [37]. McCaughan agreed. He felt that Beira was “the last place God made, nothing but sand and blacks,” but went on to note, “We all have a nigger working for us, he does all our washing.” With spare time McCaughan and his comrades were able to have “some fun deer hunting” as they were very plentiful in the area. They also caught a hyena and were aware of the presence of lions, particularly at night when they were roaring. “When we are on stable picket we have to be armed to the teeth, with rifle and ammunition, in case of beasts coming into the horse lines.” [38]

Transports at Capetown harbour, South Africa.

Tom Matson describes the country in his letter written in September from Crocodile River in Swaziland. “The river bank is covered with bamboos and undergrowth. There are monkeys chattering all day in the trees; all kinds of deer jump up as you walk along and there are snakes in abundance. The river swarms with fish that make a welcome change in our diet. … There is a krall or native village about half a mile from here full of naked Swazis. They have funny little houses like bee-hives. They are made of grass and the door is so low they have to crawl in to it. … I have not seen lions and elephants yet but they are not far off. I would rather be home.” [39]

Private Fisher of Cheltenham, a member of the First Contingent, wrote home on December 16, 1900 after a forty-seven hour journey by train to the Orange River. “The country is dotted over with bushes similar in appearance to the box thorn, and rocky hills called ‘kopjes’, about half a mile in diameter, a few being two or three miles long.” [40] He was very disappointed with the country because of the numerous kopjes but commented on the splendid water which could be obtained by sinking a bore twelve feet into the dry veldt. Rain was infrequent but when it did rain within twenty minutes the dust was flying again

Germaine writing from Maradellas claimed the Boers were frightened when they learned of the Australians arrival and apologised to his readers for not being able to report the Victorian troopers’ superiority over the Boer in action due to lack of contact. “We are willing enough,” but he indicated, “Even if we see no fighting the trip will do us good, as we see new country, and there is nothing like military discipline to make you ‘sit up’.” [41] Others expressed their desire to ‘have a go’ at the Boers.

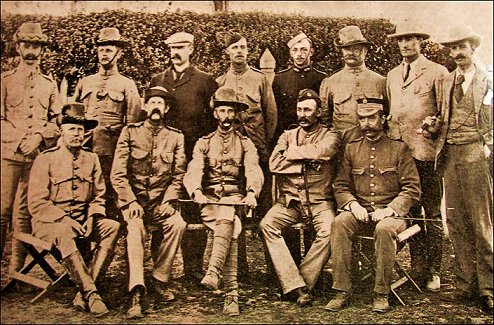

Officers of the Third Victorian Contingent: Lieut W Strong, Lieut G Moore, Mr Cameron, Lieut H Trew, Lieut J Holdsworth, Lieut W McCulloch, Vet-Lieut Stanley Fletcher

Lieut R Gartside, Captain D Ham, Colonel A Otter, Captain W Dobbin, Captain J Griffiths.

Footnotes

- Holloway, David, Hooves, Wheels & Tracks: A history of the 4th/19th Prince of Wales Light Horse Regiment and its predecessors, 1990 p 26.

- Holloway, David, Ibid., p61.

- Holloway, David, Ibid., p42.

- Brighton Southern Cross December 1, 1900.

- Cheltenham Leader, December 15, 1900.

- Holloway, David, Ibid.

- Moorabbin News, July 21, 1900.

- Moorabbin News, September 29, 1900.

- Holloway, David, Op cit., p71.

- Brighton Southern Cross February 3, 1900.

- The members listed as dying Will Christie of 3rd Contingent a nephew of Mr Goodison of Cheltenham, died of enteric fever at Rustengburg hospital Moorabbin News, December 15, 1900, F Clay killed in action at Elandshock, J Collins died at Wilmansrust and F Fisher.

- Brighton Southern Cross April 28, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross April 21, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross February 24, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross March 3, 1900.

- Cheltenham Leader March 17, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross March 10, 1900.

- Cheltenham Leader, March 17, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross March 10, 1900.

- Cheltenham Leader March 10, 1900.

- Cheltenham Leader March 17, 1900.

- Moorabbin News April 28, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross May 5, 1900; The report in the Moorabbin News April 28, 1900 indicates that it was Colonel Kelly who made the response.

- Brighton Southern Cross April 21, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross May 5, 1900.

- Moorabbin News April 28, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross April 21, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross May 5, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross January 20, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross January 27, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross January 20, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross January 27, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross June 27, 1900.

- Moorabbin News May 12, 1900.

- Moorabbin News June 2, 1900.

- Moorabbin News June 16, 1900.

- Moorabbin News June 16, 1900.

- Moorabbin News September 1, 1900 - letter written June 25, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross Nov 24, 1900.

- Cheltenham Leader February 3, 1900.

- Moorabbin News September 29, 1900.