Poultry Farming at Dingley

For decades poultry farming was an important industry in the Kingston area. This was acknowledged in the seal of the Shire of Moorabbin where a cockerel was featured in the top right quadrant. Writers in the local press gave advice on breeding, feeding, marketing and other matters of concern to anyone keeping fowls. In 1914 poultry farms were spread from Ormond, through Cheltenham and Mentone to Mordialloc.[1]

Seal of the Municipality of Moorabbin.

In 1955 Ron Coughlan bought ‘WillowBend’, a poultry farm in Spring Road, Dingley from Chris Howe. The property had a septic tank system and both power and water were connected but as Ron explained the water supply was poor. “We were still under State Rivers and it was still the old wooden pipe line. We would connect up a thousand gallon tank at the end of the hay shed in the summer time. To keep the drinkers going for the fowls we used to have to switch off the main and switch on the thousand gallon tank to keep the drinkers up.” [2]

“The power was very poor. We were right at the end of the line. We used to have a job to even get a jug to boil in the wintertime during the peak period. We had an electric stove but it wouldn’t even cook a meal there was such a drop in power.”

“There were four rows of poultry pens each of which were divided into five units. Each unit held about one hundred fowls. So the farm consisted of about two thousand birds which was the norm for poultry farms at that time,” said Ron. “Day old chicks were bought and placed in a four tier brooder in a room set aside for this purpose. The chickens were kept in this warm environment until they were about one month old when they would be gradually be transferred to a weaner where there was no heat. There they remained for a fortnight before being placed in ‘colony runs’ - little sheds with a run for them to exercise and grow. From there they were placed in the pens.”

Birds in shed on Coughlan’s Poultry Farm 1957. Courtesy of Ron Coughlan.

Running a poultry farm was not a very profitable business in the sixties. As Ron Coughlan explained, “We scraped a living but it was really just a scrape.” The birds were kept for one season because the farmer couldn’t afford to carry them through the moult period, a time when the fowls dropped their feathers and didn’t lay eggs. Day old chicks were brought in four times a year so that a continuous supply of eggs could be maintained. The older birds outside their laying period were sent to the market at Bentleigh Poultry Auctions for sale as table birds. As Ron commented, “They were only twelve months old so they weren’t bad for eating.”

The day old chicks had to be fed for up to four and a half months before they laid their first egg which was comparatively small. Few purchasers wanted these small eggs weighting up to a maximum of an ounce and three quarters. It took another month before the birds were producing the readily saleable two ounce eggs. Ron Coughlan had a customer at the Pier House Café in Mordialloc who appreciated the smaller pullet eggs. Ron explained “They liked the small egg because they would sit nicely on a hamburger. They used to take thirty dozen every week but other shops were not interested.”

Ron Coughlan’s main customers were half a dozen local shops. If there were any eggs in excess of the need of the shops they were sold to Mr Buchan of Noble Park who had a stall in the Prahran market. Other customers of the Coughlans were golfers. The Coughlan property abutted onto the Kingswood Golf Links and after a round of golf some players would call to collect cracked and double yolker eggs. “They would take the whole eggs as well as half a dozen cracked eggs to make a cake when they got home. We had no trouble in getting rid of cracked eggs. We also used a lot ourselves.”

Raising poultry had its problems. Leucosis, a type of paralysis, was a disease that would attack young birds. Ron commented, “When you went out into the run of about four hundred you would find half a dozen with a wing down or dragging a leg. You just had to destroy them and bury them. Some years the problem was so bad you could lose up to a quarter of your flock.” In earlier years flocks were also cleaned out by fowl pox but with the introduction of an inoculation program this problem had been eliminated. All birds when about a week old were inoculated by a visiting veterinarian

Pecking was also a problem. “If a fowl in a pen of one hundred birds had a spot of blood on it other birds would attack it. Young birds were a problem. Birds laying eggs were very soft around the vent, where the egg came out, and if there was a speck of blood there other birds would attack. The solution was to use stuff called PickPaint, a vile smelling and tasting liquid. The minute a bird showed a bit of blood you got a feather and dipped it into PickPaint and put it on the bird. You put it on a few birds which had blood on them and that used to stop the action of the aggressive birds. Nevertheless we used to have a reasonable mortality rate. Sometimes if you didn’t check the birds you might later find half a dozen dead ones. We used to hurriedly grab affected birds if they were alive and chop their heads off, and clean them. They were good eating. Pecking could also be a problem with the young chickens in the brooders but we found the solution was a red light. This way the chickens couldn’t see the blood.”

Foxes, mice and rats can also be of concern for the poultry farmer. Ron recalled he did not have a problem with mice or rats at Dingley although there was a rat plague on one occasion. “We had rifle which fired very small shot, similar to a shot gun, and our son with his mates used to love going around with it and a torch. They cleaned up the rats in a very short time! They were never a problem but we had a few foxes. I didn’t realise they were there but our neighbour Joe Souter who had the market garden next door asked me one morning if we were missing any fowls as he had feathers all through his garden. We did a count and found we had lost twenty five birds from a pen of one hundred. There was a hole in front of the three feet long galvanised automatic drinkers. The fowls had to put their heads out to drink. Evidently the fox used to come up in the early hours of the morning and drag the fowl through the little space.

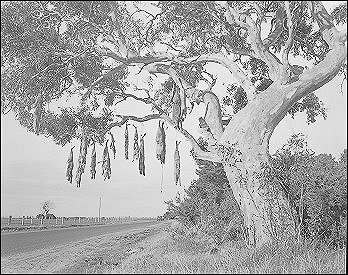

Dead foxes hanging from tree in McLeod Road, Carrum 1964. Leader Collection.

In the 1960s the birds were fed a commercial product and green feed but in the early days they were fed a hot mash consisting of maize and molasses. Ron Coughlan said that the hot mash practice had died out before he entered the business. He used clippings collected from cutting the grass in his own property but also the clippings from the greens of the Keysborough Golf Club together with the commercial pellets. He explained he collected the clippings twice a week from the club. “The birds loved the green stuff. If you didn’t give them green stuff the egg yolks would have been very pale. Nowadays they put something in the pellets to achieve the same purpose. In addition to the pellets and green feed the fowls were fed shell grit. This provided calcium which was important in forming the egg. Ron travelled twice a year to Point Henry in Geelong to get a eight bags of shell grit. “There was a farmer down there whose place used to run down to the water. He had beautiful shell grit. It was a fine spiral shell. Besides the shell grit we also placed a small dish of little pieces of granite in the pens. They would eat this fine granite chip which would lodge in their gizzard and help them grind up their food.

Besides feeding and watering the birds and ensuring they were free of disease a major task of the poultry farmer was to collect the eggs. This was done a minium of four times a day. Each bird needed fourteen to sixteen hours of light to feed, form and lay an egg so in wintertime farmers used automatic light controls in the sheds. The lights would be turned on at two o’clock in the morning and the hens would start laying two hours later. To avoid breakages and the consequential mess it was important to collect the eggs regularly and frequently. Ron explained, “Birds are funny things. Even though we had up to twenty nests in each pen they all wanted to deposit their egg in the one nest. You would probably find a dozen eggs in one nest and the others empty. This meant we needed to start our first collection for the day by six o’clock. Otherwise we finished up with broken eggs and once the other eggs in the nest were soiled they took a lot of cleaning.”

Because many of the poultry farms were in the business of producing eggs roosters were not welcome. Roosters were weeded out early and drowned. Ron explained, there was no market for them. .Once the chickens were hatched a chicken sexer determined the sex of the day old chick and the males were dumped into a bucket of water.”

Chicken sexers were very successful in their job. Ron would buy day old chicks in batches of five hundred and in that group only get one or two roosters. The skill of chicken sexing was developed in Japan and the original Australian workers went their to learn the skill. Now this is not necessary. Training is available in Australia “Chicken sexers take a day old chick and open its vent,” said Ron. “They can see some little thing and tell the difference between a rooster and a hen. Those who are proficient can do a chicken in two seconds. It requires keen eye sight but it is something you have to be taught.”

The adult birds were constantly assessed for their egg laying capacity. Those that were not laying were culled and sold for meat. “By looking at a bird you could tell that it wasn’t laying. You would turn it over and if you could get two fingers between the pelvis bone you would know they were still capable of producing an egg but sometime the pelvis bone was closed up so you knew there was no way that bird could be laying. With a good layer you would get three fingers in between the pelvis bone where the egg came out. When it got down to two it was doubtful but when it got down to one you knew that bird was not laying so you tossed her out.”

According to Ron Coughlan egg production was a hard industry to be in. In the sixties there were no controls. Anyone could set themselves up as a poultry farmer. The result was over production. To dispose of this surplus, egg pulp was exported to markets mainly in South America. But the financial returns were small. In addition the local industry had to subsidise this action. “We had to pay a levy on each egg sold. Every month we sent to the Egg Board a return recording the eggs that had been sold. We were actually working for the Egg Board. Anyone who didn’t have a producer agents licence had to send all their eggs direct to the Board. We had an outlet to shops and we were also able to sell to people who wanted to buy a dozen eggs. But we had to account for every egg that was laid.”

“In an effort to improve the egg quality all producer agents or registered poultry farmers were issued with a stamp by the Victorian Egg Board. Every egg had to be stamped with the number of the producer. By this means complaints in regard to egg quality could be easily traced back to the producer concerned to ‘please explain’.”

Later the industry got in such a bad way that controls were brought in. Quotas were put on farms. This came about because farmers were changing from deep litter farming in pens to birds in cages. “Where there was space for about 3000 birds in pens they were able to accommodate up to 50,000 birds in cages. The cages about two feet off the ground had wire sloping floors. The birds just laid the egg on the floor and it rolled down into a chute at the front unlike the pen system where there were nesting boxes. With this new system poultry farming boomed. Those farmers persisting with the pen approach were generally engaged in producing the fertile egg for breeding purposes.”

Gradually the Coughlans reduced the number of birds on the property until they ceased egg production altogether. “For about six months we didn’t have any birds at all. A chap came around one day from Farm Pride Poultry and asked if we were interested in putting in birds for the fertile egg. For this program you had to have the fowls on the floor to allow the roosters to mate with the hens. They supplied you with the birds, the roosters, and the feed. All we had to do was look after the birds, collect the eggs, fumigate the eggs in a big wooded box, making sure they were clean and then deliver them to Hockey’s Hatchery in Bentleigh. It was a good arrangement.

“In 1975 the owner of the market garden next door received an offer from Ready Mix Concrete to purchase his land for sand extraction. He came and saw me to suggest we work together on the deal. In sand extraction you had to leave thirty feet between there and the neighbour next door. Thirty feet of sand sixty foot deep was a lot of sand. His idea was that we enter into an agreement with Ready Mix making the arrangement more attractive and hence generating a better sale price. We agreed to sell.”

“The bulldozer was put to the pens knocking them down and pushing them into the batter wall around the sandpit. We remained on the property for twelve months as they were in no hurry to commence their operation. But it was the end of our involvement in the poultry industry in Dingley.”

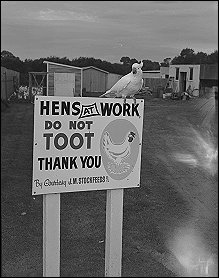

Hens at Work, Broadway, Bon Beach. Leader Collection 1966.

Footnotes

- Moorabbin News, May 30, 1914.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Ron Coughlan, August 2000.