Wilmansrust: The Debacle in South Africa

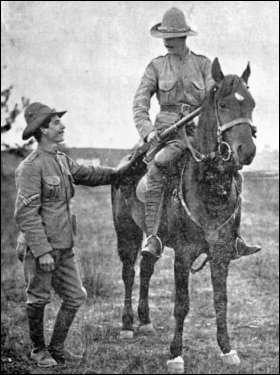

Members of a Victorian Contingent in South Africa.

James Collins of Cheltenham left Melbourne on February 15, 1901 for South Africa with the Fifth Contingent of the Victorian Mounted Rifles to fight the Boers. On June 13, 1901 he died of stomach wounds at Wilmansrust the morning after a fiasco that cost the lives of eighteen Victorians. Four officers and thirty eight men from the Fifth Contingent were wounded and a large number of men, although later released, were taken prisoner,. [1].

Writing to his sister ten days before his death, Collins wrote about his encounters with the Boers, “They tried to surround us. They were firing from behind and on both sides of us. I never expected to get back alive. The air was full of bullets and they chased us for four miles. My horse fell, and I had to run for cover.” He concluded, “It is a very sad life and I don’t care how soon it ends ”

James sent his letter in a black bordered envelope written on paper taken from a copy book which had the headings ‘An honest man is the noblest work of God’, ‘Cease to lament for that thou canst not help.’ and ‘Behind the cloud is the sun, still shining’. The reporter for the local newspaper, where the letter was published commented, “This, no doubt, is only a coincidence but taken together with the sentiments in the letter, it seems to point to the fact that Collins had a presentiment that he would not come out of the war alive.” [2]

By June 1901, the nature of the military tactics used by Kitchener, the British commander, against the Boers had changed. Rather than fighting large-scale battles, the focus was on guerrilla activities and attrition. Women and children were interned in concentration camps, crops were burned and livestock removed. Mobile bands of troops were used to counter the activities of the Boer commandos. R G Keys of South Moorabbin wrote of making captures of large numbers of prisoners and cattle and having brought in large numbers of Boer families. “We have also burnt thousands of acres of grass and a number of farms and have destroyed everything of any use to the Boers.” [3]

Private F W Collins of the Fifth Contingent wrote, “What I can see of the war is that the Boers can keep it on as long as they like, the only way is to starve them out. They get right in the mountains, and there are bullets whizzing about you and you cannot see any enemy. We are going from daylight till dark, up at 4 o’clock in the morning, and it is sometimes midnight before we get in again, so you can imagine we feel quite knocked out. When I get back to old Victoria I’ll do nothing but sleep. [4]

In June the Fifth Contingent was part of a column at Middelburg in eastern Transvaal commanded by Major General S. Beatson, a distinguished Indian army cavalry officer. Under his direction the Victorians were split into two wings. The left battalion, consisting of companies E, F, G and H, along with two ‘pom-poms’, (one pounder automatic maxim guns) was under the command of a British officer, Major Morris who had recently arrived in South Africa from India. The senior Victorian officer was Major William McKnight of Cheltenham.

Major Morris, with sufficient rations for two days, had been instructed to make a sweep to the south with his 350 strong flying force, and on the afternoon of June 12, 1901 they camped on a farm named Wilmansrust, twenty miles south of Middelburg. Trooper White of Caulfield and a member of H Company wrote in his letter home that they had been camped for about two hours when three Boers approached. [5] When they were in range they were forced off by fire from the pom-poms but this enabled them to establish the position of the guns. It was about quarter past eight when the Boers returned in strength.

“We had just had our tea and got our issue of rum, which we get every second night out here, and I had just got into bed, when they opened fire, and thank God our horses were between us and them, because the first volley mowed our mounts down like a gust of wind. They all dropped like one, or else there would not be one of us in H Co. alive today.” White continued to describe the panic in the camp following the first volley. “You could not shoot on account of not knowing which were your own men in the dark. … I was in bed when it started and had taken off my coat and overcoat and put them over my bed, and when I got them back again there were five holes in the coat and the left arm of the overcoat was blown to pieces with explosive bullets. … Two of my mates on the right of me were both shot dead, whilst three others were very badly wounded, and one of them has since died; poor fellow, he was shot through the stomach and suffered terrible agony.”

Trooper Chas Redstone of Cheltenham, a member of the picket on the perimeter of the camp, in his letter printed in the Brighton Southern Cross, described the arrival of the Boers. We did not expect anything unusual … The Boers crept up and were lying within 30 yards of the camp for twenty minutes before they attacked. A lot of our men were cooking in front of the fire; some had gone to bed because we had to start out in the morning at half-past three. …At quarter to eight the Boers put the first volley in and then they rushed the camp, shooting as fast as they could pull their triggers, never attempting to put the rifles to their shoulders. .. They ran along the line of saddles and shot men in their beds.”

Trooper White explained that the fight was short and deadly. The Boers had departed from the camp site within two hours of the first shots being fired. They took with them the two pom-poms and all the ammunition and food they could find as well as what could be scavenged from the dead. “One of them took a purse from me and a few shillings that was in it, all that I had left from my last pay, and asked me what sized boots I took? I told him ‘fives’ and he said that he wanted a pair of ‘sixes’ as his were worn out,’ wrote White.

They took Trooper Redstone’s watch and chain and belt with £2 in it but, as he said, “he was glad to get away with his life.” He went on to describe the predicament of one of the attackers, “One of the Boer’s shot himself through the foot. He was taking a badge off one of our fellows and rested his rifle on his foot, muzzle down, when it went off blowing a few of his toes off. I wish it had been his head. I might say that half of them that attacked us were not Boers; a lot were Americans, Irish and other nationalities, they could all speak good English.” [6]

When the attackers withdrew with their booty the remaining men of the Fifth Contingent attended to the wounded as best they could, as their doctor, Dr Palmer, had been killed in the initial attack. Redstone said it was a bitterly cold night as a group of them nestled amongst the rock about 1000 yards from their original camp. At the break of dawn about half a dozen Boers approached to muster some cattle. When challenged they wheeled their horses and retreated but fire from the Victorian troopers killed one Boer and wounded another. The dead Boer was the son of General Grobler. When the body was searched it was found to carry only twopence, a bible, and a lot of blood stained papers which were left untouched.

One hour later a large body of Boers returned but retreated with the arrival of the relief group who had been camped seven miles away. Lance Corporal Arthur Ruddle was with the right wing of the Fifth Contingent when it arrived at the sickening scene of the disaster that morning. He likened it to a slaughter house not a battlefield. Trooper White wrote that the ambulance came up for the wounded and then they set to work to bury the dead. “We dug one big hole about six feet deep and twenty feet long, as we had eighteen killed in all, and we buried them all in the one hole, put stones on top and a fence around” before marching off to join the right wing. [7] McKnight’s report indicates that 18 Victorians, Captain Watson of the Royal Artillery, one Kaffir and one Boer were buried in the grave. [8] Beside the lost of human life 79 horses and about 20 mules were killed, adding to the devastation.

Various explanations have been offered as to why the tragedy occurred, including the cowardly behaviour of ill disciplined Victorian troopers. General Beatson was scathing in his remarks made over several days on the actions of the Fifth Contingent. He contended the Australians were “a damned fat, round-shouldered, useless crowd of wasters”, and later, “a lot of white-livered curs”. When he observed them slaughtering some pigs the comment was, “Yes, that’s about what you are good for. When the Dutchmen came the other night you didn’t fix bayonets and charge them, but you go for something that can’t hit back.” In his view “all Australians were alike.” [9] This did not endear him to the Australian troops. Chamberlain concluded in his analysis of the events of Wilmansrust that “Beatson was learning to fight the Boers at the Fifth’s expense, while his insults and punishments show him to have been guilty of poor leadership.” [10]

Writers have drawn attention to the spirited independence of the Colonial and Australian troops which they suggested arose from their more egalitarian way of life, and that members of the Victorian Contingent valued bushmanship more than parade ground discipline. Such an attitude is unlikely to have found favour with General Beatson, a distinguished Indian Army cavalry man who was known as a strict disciplinarian.

Trooper ‘Dick’ Adams, serving with the Tullabardine’s Scottish Horse along with several hundred other Victorians who had volunteered for service with the Fifth Contingent but missed the ballot, indicated in a letter home that the Australians had a bad name. “There was £1,500 stolen out of the paymaster’s tent one night. They searched all our kits, but could not find it. Another time some one stole the officers’ whiskey. I have done 14 days in the ‘clink’ for refusing duty and going to ‘get to’ the sergeant on picket one night. Nearly all of us have been in some trouble or other.” [11]

Lance Corporal Ruddle believed the problem at Wilmansrust was the lack of experience of the officers and the skill of the Boers. “The Boers who are left fighting are real snorters and know a bit too much for some of us.” [12] Major Morris was an Imperial officer who had recently arrived from India and was still learning what was necessary to combat the Boers. He gave orders regarding the stacking of rifles in piles, as was required by regulations, but an unwise practice when there were marauding Boers in the vicinity continually sniping at them. When the major attack did eventuate the rifles were too far away from the unarmed troopers to respond quickly. In addition the pickets protecting the camp were placed at too wide intervals, allowing the Boers easier access. [13]

Major William McKnight, as senior Victorian officer, was relieved of his command after Wilmansrust but was not blamed by his troops for the defeat. McKnight, a member of the 2nd Battalion Militia Infantry at Brighton, was instrumental, along with Rigg, in the formation of G Company of Victorian Rangers at Cheltenham where he was promoted to the rank of Captain. It was as Adjutant Captain in the Third Contingent of Bushmen that he arrived in South Africa, and during this period of service he spent several months as Paymaster, Camp Quarter Master and Officer in Command at a Base Camp as well as doing active service in the field. [14]. He then joined Colonel Otter in the Fifth Contingent at Pretoria. Otter had been his commanding officer in the Victorian Rangers. [15] Given this lengthy involvement in military affairs, it is likely he had some knowledge and understanding of regulations and the strategies being used to contain the Boers.

The officers of the Fifth Contingent selected by the Victorian military commandant, Major General M F Downes and approved by Cabinet, had a mixture of experience and youth. Prior to departure for South Africa they had up to six weeks of drill, mounted exercises, lectures on scouting, and outpost duty at Langwarrin and worked at the butts for sixteen hours each day. However many men had joined only a few days before departure and would have benefited from more training. [16]

Chas Redstone seemed less concerned about the reasons for the debacle at Wilmansrust and more about achieving some revenge. For him the focus was “to get back at a few Boers” and to “make up for that night”. Concluding his letter home he wrote, “I could not sleep for three nights after that night thinking of my mates that had gone under. I am getting over it a bit now, but that night will remain green in my memory as long as I live.”. [17]

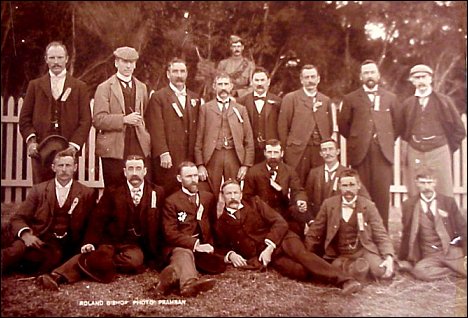

Shire of Moorabbin Patriotic Committee for Boer War. Three members named: J. Lannan, T. Mewett and W.P. Fairlam. Courtesy of Betty Kuc.

Footnotes

- Chamberlain, Max, ‘The Wilmansrust Affair’, Australian War Memorial Journal, April 1985, page50.

- Brighton Southern Cross, July 13, 1901.

- Moorabbin News, September 7, 1901.

- Brighton Southern Cross, June 29, 1901.

- Brighton Southern Cross, August 24, 1901.

- Brighton Southern Cross, Ibid.

- Brighton Southern Cross, Ibid.

- Wallace, R. L., The Australians at the Boer War, Australian War Memorial and Australian Government Publishing Service, 1976, p332 & McKnight, W., Reports of action at Wilmansrust, Australian Archives, 1901/3859, 4389.

- Age, October 1901.

- Chamberlain, Max, ‘The Wilmansrust Affair’, Australian War Memorial Journal, April 1985.

- Brighton Southern Cross, September 14, 1901.

- Brighton Southern Cross, August 24, 1901.

- Wallace, R. L., Op. Cit., page 330.

- Brighton Southern Cross, November 24, 1900.

- Moorabbin News, April 13, 1901.

- Chamberlain, M., Op. Cit., page 48.

- Brighton Southern Cross August 24, 1901.