Shindig at the Mordialloc Life Saving Club

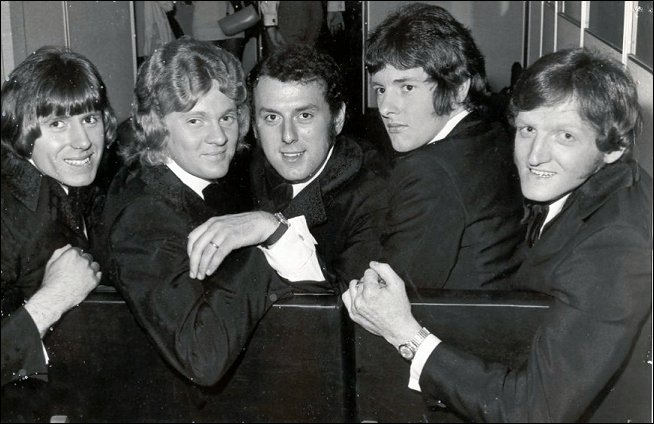

The original Paul Mackay Sound. Courtesy of Hazel Pierce.

When it started in 1957 the knockers said it wouldn’t last. But they were wrong! The dance at the Mordialloc Life Saving Club, later to be known as Shindig, continued for twenty three years under the direction of Hazel Pierce and her team. Initially called the Lighthouse, the name was changed to Mothergoose before becoming Shindig in the late sixties.

The beginning of the dance was modest, with recorded music being used, before moving to bands of live musicians, but the goal remained the same; raising money for the Mordialloc Life Saving Club to refurnish the club house after a disastrous fire and to purchase life saving equipment like reels and lines. Paul Meaney recalled that Stan Azzopardi was one of the foundation musicians who started playing the piano accordion. “They had a tea chest for a bass with a string on it, drums and an electric guitar with a ten watt amp. It was really remarkable because you have stereo equipment with more power than that nowadays.” [1] Bobby Cookson was the singer with the group called the Premiers, and he recalled the first night of live music when he sang Elvis Presley’s song, ‘Hard Headed Woman’ and the crowd going berserk even though the performance in his judgement wasn’t that good. [2]

After several years performing with the Premiers at Mordialloc, Bob Cookson left to pursue a career in cabaret, and Paul Meaney replaced him as lead singer. Over time a succession of guest bands and solo artists appeared including Colin Cooke, Johnny Chester, and Betty McWade. The Mordialloc News reported that a skinny singer called Johnny Farnham was a member of Strings Unlimited, which played occasionally. [3] Shindig provided a venue where new bands got a start and gained a feel of what audiences thought of their music. Early in the history of the dance, Stan Azzopardi was the director on the music front so he organised all the guests who performed at Mordialloc, later this role passed to Paul Meaney.

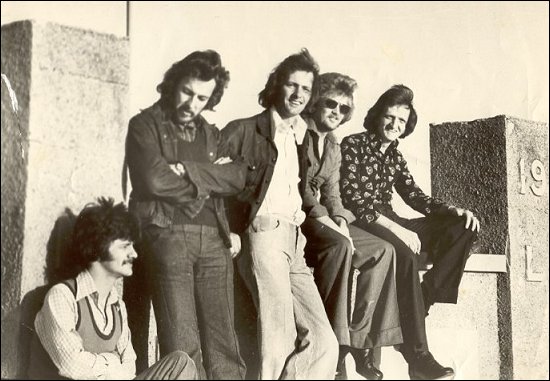

Paul Mackay Sound: From left, Les Szabo, Don Bailes, Stan Azzopardi, Peter Waddell and Paul Meaney. Courtesy of Hazel Pierce.

Paul Meaney brought several musicians together to form the Paul McKay Sound, the name of the piano player. “We thought McKay was a nice name so we used it.” [4] Paul wrote a number of songs which became hit records, a success which helped to establish the name and reputation of the band. Other records followed which Paul described as ‘moderately successful’. Appearances on New Faces, and Bandstand, popular national television programs of the day also helped the bands popularity, but during all this exposure the band returned each Sunday to perform at Shindig. This they did for fifteen years.

The music that was played was basically rock and roll; good time music designed to keep young people happy. For Ian Lyons the music was just the best, “it gave you a boost,” he claimed. From Tutty Fruity, all the Johnny O’Keefe numbers, Col Joy and Midnight Touch. [5] Peter Grant described the music as “great toe tapping stuff, music that young people today still get into. Even guys who didn’t dance could get into the grove of it and have a bit of fun.” [6] Greg Meggs described his dancing as a fairly free form involving shaking and spinning around, “but at times the place became so crowded as people moved shoulder to shoulder there was not much that could be done except shuffle. You could just stand there a jig a bit and twist a bit. There were those who really knew how to rock and people would move back and give them space and then admire the energy, combinations of moves and skill.” [7] But Michael Pierce acknowledged, “When it was crowded it was very hard to throw your arms and legs around.” [8]

The Paul Mackay Sound at Mordialloc. Courtesy of Hazel Pierce.

The dance on Sunday nights attracted teenagers, and some a little older, from all around Melbourne, not just Mordialloc. Many came from down the Peninsula, and from Collingwood, Brunswick and Prahran. Hazel Pierce said there were at least four distinct groups attending the dance. “There used to be the skin heads in one corner, they were the ones who had the short haircuts, the surfers would be in another corner, the jockeys and strappers in a third corner and the tough little ones with the leather belts and the studs and the rockers in the remaining section. But they all learned to live with one another.” [9] Greg Meggs recalled the Mordi Rockers who could be found down the front of the hall. Greg and his surfing mates, in ignorance, looked upon this group with fear as “they were dressed in black leather and used to drive Customlines and they would rock and roll. They were probably as peaceful as anyone else.” Although he was in one group he acknowledged there was a little interaction with other people on the edges. “I guess when you are teenagers you are fairly shy and you stick with your peers. There were those who accepted you and you accepted them.”

For those who didn’t want to dance or wanted to get a ‘fizzy drink’ there was the lounge room down stairs. From there, one of the participants recalled, when the McKay group were really moving you could see the floor pulsating above you. There was also a games room there with table tennis, hockey and quoits for the less active. There were also table and chairs and a television set, which could hardly be heard above the noise. On the first floor there was the veranda where people went for a breather and a cigarette.

Hazel Pierce with Barbara Morgan (left) receives Life Membership of Royal Life Saving Society from H R H Prince Michael of Kent at Government House Melbourne, 1995.

Hazel Pierce was viewed as a tough operator who had strong support from her team in maintaining harmony at the dance. Jeff Coote, who was responsible for security, had the support of three other members of the organising committee in seeing that any unruly element was excluded. They, Hazel explained, were the ‘bouncers’. Hazel herself was not averse to smacking a girl on the backside if she misbehaved. “How would you like to do that today? They would come back the next week and say ‘I’m sorry Hazel, I won’t do it again.’ The fellows would be made to sit outside. They weren’t allowed in for a couple of weeks but they still came back." [10]

Ian Lyons recalled they got the occasional complaint from the people living across the road, but the whole thing was well run and people who attended were expected to respect the people who lived around there and they did that.[11] Generally the crowd was well behaved and Jeff Coote commented, “there were only a few occasions when the police were called.”[12] Michael Pierce told of the time there was a fight in the hall and “the bouncers got hold of them and Mum was in the middle of them telling them what she thought of them and helping to throw them out. It didn’t seem to worry her. She said they won’t hit me I’m a lady.” [13]

The dance had several inviolate rules; one was no alcohol and another no pass outs. While stylish dressing was not necessary, scruffy dressers were turned away. Jeans were the mode and participants were always neat, clean and tidy according to Paul Meaney. [14] The no alcohol and no pass-out rules were appreciated by parents who felt their children were able to enjoy themselves in a safe environment. Nevertheless there were teenagers who managed to get back into the dance after leaving and there was alcohol present in the vicinity of the dance according to Margaret Buchan who said she came to the dance with her friends in F E Holdens and Ford Customlines with their eskys loaded with beer. [15]

Shindig was not a ‘one man show’ according to Paul Meaney but it was Hazel Pierce who kept her finger on the pulse and coordinated the whole show. People looked to her for direction, but she had the support of members of the club who did things like selling drinks or the tickets, and looked after the security of the place. Over the years it raised more than $110,000 for the club and gave some financial support to the musicians enabling them to develop their musical talents, and take up other opportunities. Bob Cookson remembered it was about two bob to get in and the musicians shared the door with Hazel. “We got about ten quid so it averaged two quid each. That was when the average wage for a week’s work was about eight quid. It soon got to four or five quid so that was terrific money. We learnt very quickly and we were pretty professional in twelve months and started playing big gigs like the town halls and Earl’s Court.”. [16]

Member of the Paul MacKay Sound get it together with some of the gang at Shindig at Mordialloc Life Saving Club. Group members pictured from top left are organist and guitarist Peter Waddell, pianist and organist Noel Tresider, vocalist, Hazel Pierce, organizer, Paul Meaney and bass guitarist Don Bailes, 1974. From the Leader Collection.

Early in 1980, Stephen Taylor, a reporter from the Mordialloc Chelsea News wrote that Shindig, the dance that had been the Mecca for thousands of bayside teenagers on a Sunday evening, had closed. Hazel Pierce described the situation as a tragedy. “I will probably grow old now!” was her comment. When attendances fell below twenty it was obvious that Shindig could not continue with the dance unable to compete with venues providing entertainment without the restrictions imposed at Shindig. The time of crowds of 500 had gone. Hazel Pierce saw the demise of the dance being linked to the prevalence of under-aged drinking in local hotels. She said many of these hotels were filled to capacity with teenagers on week nights and by Sunday they had spent their allowances on admittance prices and alcohol and could not afford another dance. [17]

Shindig celebrated twenty one years in 1980. On that occasion newspaper reports said the crush made it impossible to dance but it was a free night. Six weeks later it was finished. It was eleven years later, in 1991, that three hundred individuals returned once more to dance to the Paul Mackay Sound. In 2001 the crowd came back for the third time, to rock and roll and listen again to the vocals and music of Bob Cookson, Betty McWade, Paul Meaney and others of the musical team. Although still managed by Hazel Pierce and her group, on this occasion it was held at the Youth Centre in Warren Road, Mordialloc because 700 indicated they wanted to be present at this reunion and that number could not be accommodated at the Life Saving Club. It was a great occasion for reminiscing, by individuals now in their forties with families of their own, about how it was back then.

Admission ticket to 2001 Reunion of Shindig. Courtesy of Hazel Pierce.

Footnotes

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Paul Meaney, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Bobby Cookson, August 2001.

- Mordialloc Chelsea News, March 5, 1980.

- Membership of the band varied from time to time but included Lindsay Shan, Don Bailes, Peter Waddell, Les Taylor, Les Szabo, Paul Meaney.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Ian Lyons, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Peter Grant, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Greg Meggs, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Michael Pierce, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Hazel Pierce, Novemeber 2000.

- Ibid.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Ian Lyons, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Jeff Coote, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Michael Pierce, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Paul Meaney, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Margaret Buchan, August 2001.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Bob Cookson, August 2001.

- Taylor, Stephen, Mordialloc Chelsea News, March 5, 1980.