Tough Conditions on the Carrum Swamp

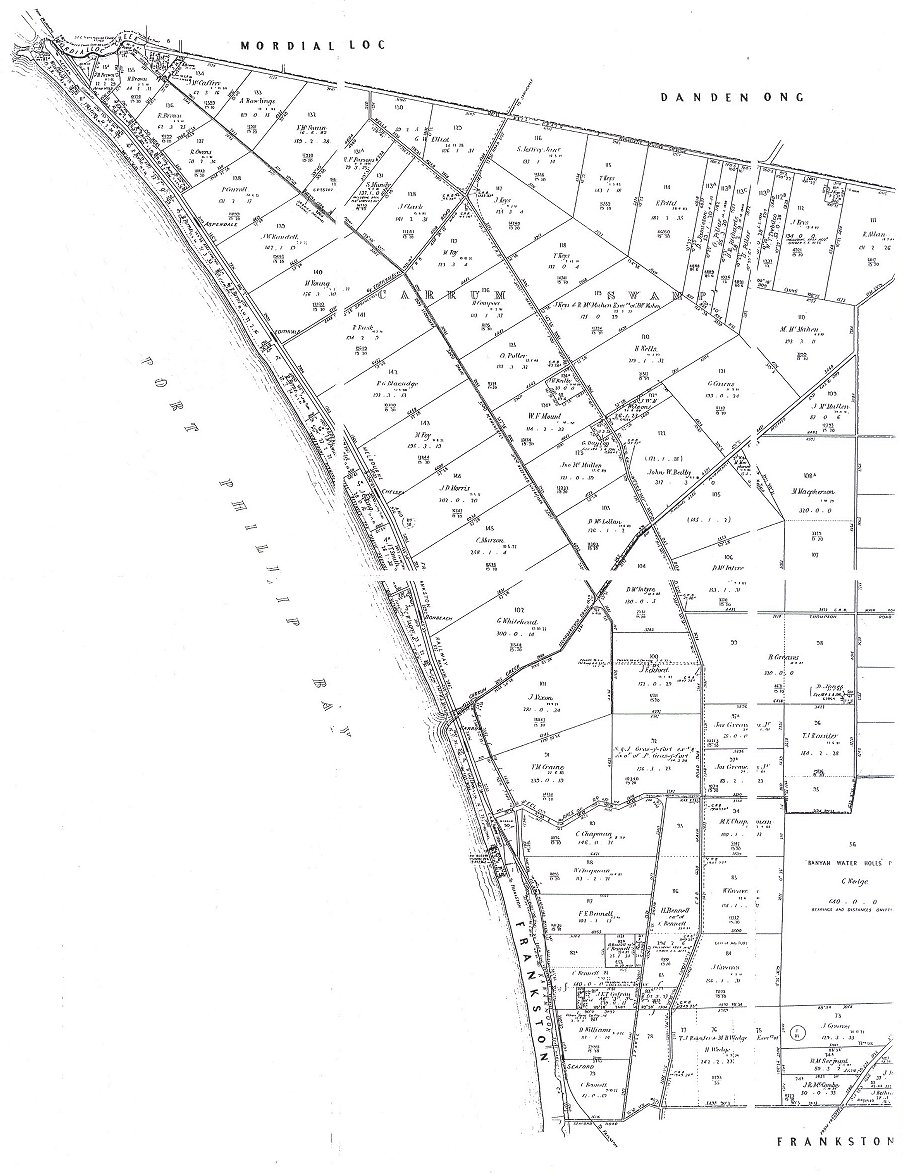

Selectors on the Carrum Swamp.

The Carrum wetlands, now an integral part of bayside suburbs, and covered with housing development, has not always been a convenient place to live. Bunurong people valued it as a source of food but initially the white man found it a difficult place on which to survive.

The Carrum Swamp, first surveyed by T C Rawlinson in 1866, stretched over 11,000 acres between Mordialloc and Frankston, and from the coastal dunes to five kilometres inland. Two years later, Hodkinson and Couchman repeated the survey noting the swamp’s rich soil and recommending to the Lands Department that with the provision of effective drainage, the land could be opened up for agricultural usage. The recommendation was taken up in part, as the area was made available for selection in 1871 with forty-nine men taking advantage of the opportunity to gain land. However, the provision of a successful and appropriate drainage system was to take many decades so the grantees had to labour under appalling conditions and to fight to get their difficulties recognised by the government.

The 1869 Land Act, under which the Carrum Swamp was made available for selection, detailed several conditions that had to be met by people receiving grants. Should all these conditions be met the selector received the title to the land and was then in a position to sell it any time he chose. However, should he fail to meet the conditions the penalty was the loss of the land without compensation for his efforts and capital investment.

Individuals could peg out up to 320 acres of land and with the granting of a licence, paid two shillings per acre rent for three years. During that time, to demonstrate they were genuine farmers, they had to fence their selection, make improvements to the value of £1 per acre by constructing dams and other structures, cultivate one acre in every ten in the first two years, and permanently reside on their selection. After three years, if all conditions had been met, a lease could be granted for seven years during which time the farmer continued to pay the rent of two shillings for every acre. Each selector could, if he wanted to and had the money, pay the seven years rent in one hit and obtain the title to the land. Holding the title, which attested to his ownership, he was in a position to sell the land if he wished. Prior to obtaining the title the selector had no transfer rights. [1]

The conditions set by the government for individuals to gain the title to the land were not easily met and caused much anguish to many selectors. The major constraint on development was the presence of too much water! The Dandenong Creek and Eumemmerring Creek discharged their waters into the swamp from where the water gained inadequate access to Port Phillip Bay through Mordialloc Creek and Kananook Creek. The broad sand ridge between Mordialloc and Frankston formed a natural barrier for the water’s access to the Bay. The first efforts to improve this situation were made by the Dandenong Road Board in 1873 when it arranged the construction of several channels to link the Dandenong and Mordialloc creeks and the Eumemmerring and Kananook creeks, but its efforts were inadequate.

Prior to this action by the Dandenong Road Board selectors on the Carrum Swamp met under the chairmanship of Mark Young at Mordialloc on March 11, 1872. The meeting agreed that the situation was desperate and that serious and immediate action was required. They proposed to the President of the Board of Land and Works that selectors should be taxed one shilling per acre per year for three years in order to finance a drainage scheme for the swamp. However, they wanted the government to agree that all future selections on the swamp, and others given rights of occupancy such as Mr Beilby and the Sugar Beet Company, should be subjected to the same tax. The tax they saw as part of their obligation to make capital improvements to their properties. The second proposal to the President of the Board related to the residency condition. Because of the flooded nature of the swamp they wanted the Lands Department to recognize that it was impossible to comply with the residency condition. [2]

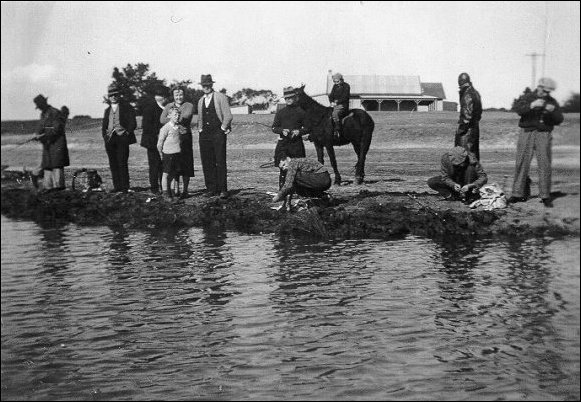

Mark Young met the residency condition, having built a substantial house on his 176 acre selection and lived there with his wife and family of six children from 1872. This was despite the fact that he could only access the back boundary of his water-logged property by using a rowing boat. Malcolm McQueen wrote that it was not a pleasant place to live, “Some of my family were often in the habit of walking all the distance with the water above our knees carrying our weeks provisions with us”.[3] Henry Comport claimed that he was up to his armpits in water in some sections of his property, and fellow selector, Norman McSwain, was unable to reside upon his land and cultivate it because during the winter there was “not one acre dry in the whole of it” making cultivation useless and throughout the year three fourths of the land was under water. [4] Given these conditions residency was impossible for many selectors.

Flooding at Chelsea 1934. Courtesy, Norman Stephens.

Norman McSwain pointed out in his letter to the Minister of Lands that he was unable to comply with the conditions of his grant. The water-inundated land was unproductive and consequently expenditure upon it was not warranted. He wrote, “I might have built a house and other buildings on it and so bring up the list of improvements and the amount spent upon it but I really could not afford it, as the land is not returning anything. I had five head of cattle and two horses on it but when the first flood came down last winter I found the cows over their knees in water where they had been for two days without any food … it was very hard for a poor man to spend money on such land.” [5]

McSwain’s plea for a lease was refused by the Department of Lands so he wrote again in July 1876 reiterating his case, stating he was a bon a fide farmer but the only way to improve the situation was to provide adequate drainage. Once this was available, he suggested, he would be in a position to meet all the conditions of the grant. [6]

Richard Rusk, James Hallinan and Harry Breed were other selectors, noted by bailiff James Kennedy, as making no improvements to the land. Mounted Constable McGrath of Frankston reported that Caleb Kennett had made no effort to clear his allotment, the land being in its original state. [7] James Nixon, a disgruntled selector being threatened with the loss of his land, wrote a letter to the Minister of Lands, naming Keys, Carroll, Coleman and Chapman as individuals amongst a dozen others who, he claimed, had made no improvements to their selections. [8]

Other selectors made some effort to fence and improve their allotments by clearing, ploughing and cultivating the land. But in some cases the value of these improvements fell short of what the Department of Lands required under the condition of the grant. George Whitehead had built a two-room residence, erected 58 chains of fencing, ploughed 25 acres of land, planted trees, and provided for some drainage but the assigned value of these improvements was less than the required twenty shillings per acre. The deficiency was noted as £160. James Nixon claimed the value of his improvements was £200.6.0 but the bailiff challenged this with his valuation of £141.5.0. [9] After a second visit to the Nixon holding, James Kennedy explained he did not include the wages paid to two men, nor the cost of red gum posts because they were not erected. [10]

At the end of 1876 a Select Parliamentary Committee chaired by James Purves was established by parliament to investigate the claims of selectors. After receiving submissions from Mark Young, Henry Comport, Henry Wells, and Edgar Pettit it concluded that the Carrum Carrum Swamp was an exceptional case and that the selectors should not be expected to reside on their allotments provided they made other improvements. [11] As a consequence no selector lost his land and many were eventually able to gain the desired title.

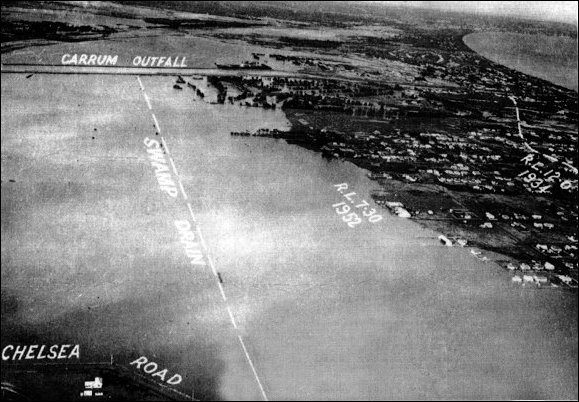

Generally, the Dandenong Road Board in 1873 and later the Dandenong Shire made unsuccessful efforts to resolve the problem of water on the swamp. [12.] When in 1878 the Minister of Public Works, J B Patterson, reviewed the situation he recommended that a channel be cut through the sand ridge to release water to the bay. The government responded to the recommendation by making £1,500 available to the Dandenong Council which, in turn, accepted the tender of £1,167-5-0 from Henry Powis to carry out the work. The 30 foot wide cutting was completed by August 1879 giving some relief. But the problem of excess water was not solved for the residents on the Carrum Swamp as floods years later in 1880, 1934 and 1952 again forced many people to leave their homes.

Aerial photograph of 1952 flood compared to the height reached by the water in 1934. Courtesy, Chelsea & District Historical Society.

Footnotes

- Victorian Government Gazette, December 31, 1869.

- Report from the Select Committee on the Carrum Carrum Swamp Selectors, 1876.

- Public Records Office, Malcolm McQueen.

- Public Records Office Unit 268, File 17920 Lyndhurst.

- Public Records Office, Ibid.

- Public Records Office, Ibid.

- Public Records Office Unit 1661 File 7231 Lyndhurst.

- Public Records Office, Unit 280 File 18847 Lyndhurst.

- Public Records Office, Ibid.

- Public Records Office, Ibid.

- Report from the Select Committee on the Carrum Carrum Swamp Selectors 1876.

- Black, N. C. The Carrum Swamp Lands Reclamation, Settlement and Flood History, Aqua, September 1957.