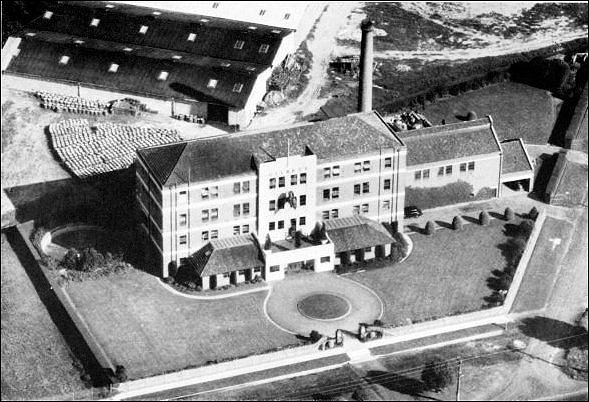

Gilbey’s Gin at Moorabbin

Aerial View of Gilbey’s Gin, Moorabbin, c1940. From Gold, Eric, Four-in-Hand: A history of A & G Gilbey Ltd. 1857-1957.

Gin found a ready market when it was first introduced into England from Holland in the 1690s. It was far cheaper than wine or brandy and easily distilled making it a common brew for many people struggling to survive in the squalor of urban living in the eighteenth century. [1] It was later, in the nineteenth century, that Gilbey’s gin was first produced and not until the 1930s that the company responsible for its production came to Moorabbin.

Two brothers, Walter and Alfred Gilbey, and a friend, Henry Gold, first started the Gilbey company. Returning from the Crimean War in 1857 they established a small cellar in London where they sold port, sherry and brandy. With advertisements in the local papers their enterprise thrived to the extent they were able to open a branch in Dublin. It was in 1872 that they expanded further by opening a gin distillery, and fifteen years later, their first Scotch whisky distillery. [2]

Fred Collins, manager of the advertising department of Gilbey’s, migrated to Australia in the early 1880s because of poor health, but he kept contact with his former employers. Perhaps because of this contact and Collins’ assessment of a potential market, the Gilbey brothers decided to use him to develop the Australian and New Zealand trade. By 1927 Gilbey’s imported produce was facing increased competition from locally produced gin, so the company adopted the strategy of shipping their product at a higher strength in drums to be rebottled in Australia, effecting a considerable saving in duty and enabling the price to the consumer to be brought down to meet local competition. A site for the bottling establishment was purchased in West Melbourne but in the 1930s it was decided to construct a distillery and bottling plant in Moorabbin. [3]

The Moorabbin Shire Council was interested in attracting industry to the municipality because industry provided employment opportunities for a growing population and strengthened the financial basis of the Council through the rates it paid. At the meeting of Council on May 18, 1936, F. N. Collins, the solicitor representing Gilbey’s, explained that the company had obtained an option to purchase land on the corner of Point Nepean Road and Exley Road and it was there the company intended to build a modern distillery. However, before committing themselves to the project they required the Council to rezone the land from its classification of residential to industrial.

Following the display and explanation of a model of the proposed building by the architect Mr Kingsley, Cr Forbes gave notice of a motion that the area identified by Gilbey’s be declared a factory area. Once confirmed by Council, Gilbey’s indicated they would construct the four storey brick building on the four acres of land, with a separate boiler house and garage. The estimated cost of the project was £50,000. Cr Forbes said he realised the importance of the industry to the municipality and he considered any objection had been satisfactorily explained away. [4]

But not all individuals and groups in the community approved the Gilbey’s proposal. Mr R F Campbell, claiming to speak for the Bentleigh Branch of the Independent Order of Rechabites, objected to Gilbey’s plan saying it would “make a hot potch of Point Nepean Road, it was near a school, and would detrimentally influence the young.” [5] The Rechabites opposed the Council’s intention to rezone the land to allow Gilbey’s to build a distillery there for the production of pure white alcohol.

Other temperance groups also protested against the issuing of a permit that allowed the construction of a distillery on the nominated site in Moorabbin. They requested that the Council decision be rescinded. This view was supported in a petition presented to Council signed by thirty ratepayers who objected to their councillors’ action. [6] Despite this antagonism the Council confirmed its original resolution. As Cr Allnutt said, “Opposition to the measure had been raised too late.” [7]

Councillors believed they were honour-bound to stand by their original agreement reached with the company in May 1936 as the company had proceeded with the purchase of the land on the understanding given by the Council that the land would be rezoned. Besides, they were aware that there were other municipalities where Gilbey’s could pursue their interests if Moorabbin turned them down.. For the majority of councillors such an occurrence was not in the long term interest of the municipality. It was an opportunity that should not be lost.

On Wednesday, November, 3, 1937, over a thousand people were entertained at the official opening of W & A Gilbey at Moorabbin, an occasion when the local product was liberally dispensed. [8] Richard Casey, Federal Treasurer, officiated at the opening in the absence of the Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons. [9] In his speech he pointed to government imposition of custom and excise duties, which, he believed, encouraged companies like Gilbey’s to come to Australia. As Treasurer he acknowledged that excise duty in the previous year had raised about £2 ¼ millions for the government coffers, “not an inconsiderable sum, even for a treasurer,” he commented. But he went on to express the wish that the company should prosper, and “raise that sum to a respectable figure.” [10]

Guests at official opening of Gilbey’s Distillery, 1937.

In November 1960 the company expanded its operation at Moorabbin by building a new £250,000 facility adjoining the existing building. With this extension all aspects of the company’s operation were centralised at Moorabbin; including bottling, delivery, sales, administration and distilling. Production was doubled with the installation of high-speed modern machinery. [11]

The News reported that the gin was piped from the distillery to the vatting gallery and then drawn on to the bottling line, where bottles were filled, capped, labelled and packed into cartons in one continuous operation, touched only once by the operator before being taken to the assembly line. Liqueurs made by Gilbey’s were mixed and blended in a ‘liqueur kitchen’. Bottles were washed in a giant machine capable of transforming 3000 dirty bottles into clean bottles in one hour.

Since its opening Gilbey’s had expanded the list of products distilled, bottled and stored at Moorabbin to include Australian whiskies, liqueurs, Jim Beam Bourbon, Hennessy Brandy and Smirnoff Vodka. By the 1980s eighty people were employed to achieve the company’s goals but in March of 1983 a major change was made to the company’s marketing structure. Gilbey’s merged with Castlemaine Toohey’s and Lion breweries of New Zealand to form a marketing company known as Swift and Moore. [12] While production continued at Moorabbin the functions of marketing and sales moved to an address in Cheltenham.

Less than two years later, in 1985, the decision was made to move the company to New Zealand and to cease its operation at Moorabbin. Mr Dowett, a union representative, claimed this decision was brought about by the government’s imposition of the exorbitant excise duty of 85 per cent in 1978, making it impossible for the company to compete with imported brands. “The government was taxing the spirit industry into oblivion,” he said. Stephen Goodwin, the production manager at Gilbey, acknowledged the company was progressively closing down and that sixty four people would be out of work as there was no viable distillery to which employees could be transferred. [13]

In September 1985, A T Cocks & Partners approached Council asking that the zoning of the Gilbey’s site be changed from light industrial to allow them to redevelop the property for office accommodation, a restaurant, and a sporting complex complete with a pool and tennis courts. The developer claimed the aim was to create an attractive business environment with landscaped forecourts, and pedestrian paths. The two landmark buildings used as a bulk store and a distillery were to be retained.

The Council rejected the Cocks proposal arguing it was in conflict with their strategic plan which focused on Cheltenham as the commercial centre for the municipality. This ‘conflicting view’ was disputed by Phillip Steere of Cocks & Partners who saw their Moorabbin development as complementing the Council’s Cheltenham plan. He said it was not a major redevelopment but rather a refurbishment of existing buildings. Moreover, if the redevelopment plan did not proceed, he believed the buildings would simply fall into disrepair and would eventually be demolished. [14]

At that time the Moorabbin Council, desperate for additional space for its officers, had already explored the use of the Grange, a property on Nepean Highway, for this purpose but rejected it after a bitter controversy raged amongst councillor and the members of the public. The Gilbey’s refurbishment offered another option to solve the space problem as 80,000 sq. ft of office space was available. However, the possibility was rejected. Bill Jacobs, the town clerk, told the Moorabbin News that although the developers had made no formal offer to the council an inspection of the buildings showed they would require considerable reconstruction if they were to be made suitable for offices. [15]

In 1985 the Reg Hunt Rhodes Motor Company took over the building and its surrounding site for their car sales operation. After fourteen years the car company informed the Kingston Council of their intention to demolish the building, having received a permit to do so from Procheck Building Surveyors on January 28, 2000. Structural engineers had advised the company that the building was affected by advanced deterioration of the concrete beams and columns, that the structure had reached the end of its useful life, and that the building was a safety risk in its present condition. [16]

Reg Hunt Motors at Gilbey’s Gin, 1999.

Council officers, arguing that the property was of historical significance, moved quickly in an effort to protect the site. The Minister of Planning, John Thwaites, was asked to place a interim heritage control over the building and tower, and Heritage Victoria was requested to consider whether the building should be placed on the Victoria Heritage Register. [17] Living Histories and Associates were commissioned to report on the historical and cultural significance of the building. [18]

An Interim Protection Order was issued for a period of four months allowing the Council officers time to resolve the tension between two objectives of the Planning and Environment Act 1987, one which sought to provide for the fair, orderly, economic and sustainable use and development of land, while the second aimed to conserve and enhance those buildings of scientific, aesthetic, architectural or historical interest.

Demolition of Original Building viewed from Exley Road, 2000.

Ultimately, the Heritage Council assessed the building as not warranting State heritage listing, the Interim Protection Order expired and the Council agreed to the demolition under several conditions, including the completion of a photographic record of the building in both colour and black and white by a professional photographer. In June 2000 the building came down to be replaced by a shopping complex.

Shopping Complex on the Original Site of Gilbey’s Gin, 2002.

Footnotes

- Haigh, C., (Ed), The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland, 1985.

- Gold, A., Four-in-Hand: a history of W & A Gilbey Ltd, 1957.

- Gold, A., ibid.

- Moorabbin News, May 23, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, July 11, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, July 11, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, July 11, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, November 6, 1937.

- After a distinguished career in international affairs and politics Richard Casey, as Lord Casey was appointed Governor General of Australia from 1965 to 1969.

- Moorabbin News, November 6, 1937.

- Moorabbin News, November 2, 1960.

- Moorabbin Standard, September 30, 1983.

- Moorabbin Standard, July 31, 1985.

- Coote, G., Gilbey’s site as council offices?, Moorabbin Standard, Wednesday, September 11, 1985.

- Moorabbin Standard, September 11, 1985.

- Woodland, M., Heritage Status of the Former Gilbey’s Gin Building, Council Minutes, February 28, 2000.

- Woodland, M., ibid.

- Sheehan, M., & Moylan, G., Gilbey Distillery Complex Moorabbin: Cultural Heritage Assessment (Preliminary Report) 2000.