Trams

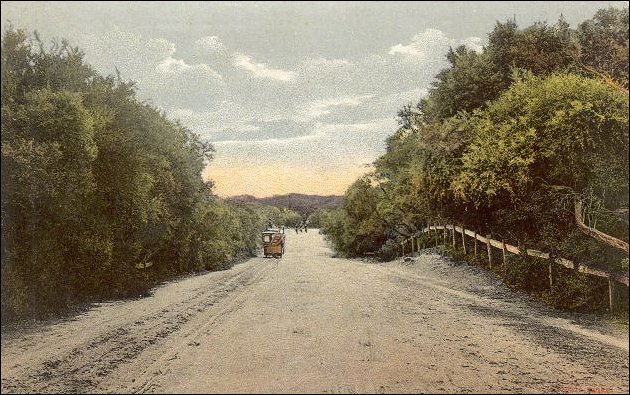

Horse Tram on Beach Road amongst the Ti-Tree Groves, c1900. Courtesy Jean Martin.

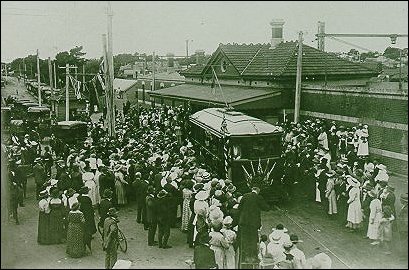

From 1889 to 1915 the Beaumaris Tram Company conducted a horse drawn tram service from Sandringham to Cheltenham through Black Rock and Beaumaris. Towards the end of that time the company experienced great difficulty in maintaining the service in the face of increasing costs and declining patronage. The year nineteen fifteen saw the demise of the service but community interest in trams continued. [1] An electric tram service was instituted in 1919 from Sandringham to Black Rock on a route that slightly differed from that followed by the horse powered models. Seven years later the service was extended to Beaumaris on the understanding that residents of that district would meet some of the losses that might be amassed by extending the route to a scarcely populated area. [2]

Official opening of the Sandringham-Black Rock Electric Street Railway at Sandringham 1919. Shows Tram No 22, the first car moving out. Courtesy the Sandringham and District Historical Society.

Several of the Beaumaris neighbouring communities wanted to tack onto the Sandringham/Beaumaris line but to achieve this goal the Railway Commissioners had to be convinced that the proposals were financially viable. The Cheltenham Beaumaris Tramway League Committee was formed to promote Cheltenham’s cause. Following a meeting on November 10, 1926, a local politician informed the committee that, despite the Shire’s support, the matter was unlikely to be considered because of a pending election. It was not until July 19, 1928 that the committee was reconvened to prepare a case for presentation to the Standing Committee of the Railways [3]

The proposed route was the shortest distance from the beach to Cheltenham; from Tramway Parade to Cromer Road, along Balcombe Road as far as Charman Road and then to the Cheltenham station. This route, it was argued, would provide the Moorabbin Shire with an outlet to the beach while providing an additional source of revenue for the service. Figures on population growth were assembled with the assistance of the Shire Secretary. They showed that the number of residents in the Cheltenham Riding had increased by five hundred and sixty six people to a total of 4,113 over a three year period, and five hundred and eighty buildings had been erected in the Shire since October 30, 1927. [4] One supporter of the Cheltenham proposal believed the area had outdistanced Mentone in terms of buildings and development but provided no data to support his claim. [5]

The vision of the Cheltenham committee was not restricted to the Beaumaris to Cheltenham route as they saw the possibility of future extensions. One was along Centre Dandenong Road to Dingley and Dandenong, ‘an area fairly well populated.’ A second was from Centre Dandenong Road along Moorabbin Road (now Warrigal Road) to Oakleigh to serve the Cheltenham Benevolent Homes, the Sanatorium and the Golf Links. The Superintendent of the Benevolent Homes told the people attending the Cheltenham Beaumaris Tramway League meeting that his institution constituted one of the largest hospitals in Victoria with 700 patients, 32 nurses and 50 other employees. The number of visitors on a Sunday was from 250 to 300 and 150 to 200 on a Wednesday. There was also a large number of visitors to the home to give the inmates different forms of entertainment but the trouble was the lack of suitable transport. Trams he suggested, “would be a boon to them and to the consumptives at the Sanatorium.” [6]

In addition to the Benevolent Homes there were other institutions, it was observed, that would benefit from introducing a tram service. The Cheltenham Cemetery was listed, no doubt for its visitors and not inmates, together with the Church of England, Convent of Mercy in Cavanagh Street, the Methodist Children’s Homes, and the Convalescent Home for Men.

As sections of the land along the route were under development, it was claimed that the number of potential customers was likely to improve. Moreover, it was pointed out, many residents of Beaumaris already were travelling to Melbourne each day via Cheltenham rather than using the existing tram route because the Sandringham station was too distant. Another link between Cheltenham and Beaumaris related to business. Many Beaumaris residents made use of the post office, police station and banks, as well as doctors, estate agents, private hospitals and dentist, all located at Cheltenham.

The Beaumaris Tramway League, after discussion, lent support to the Cheltenham case. While one speaker feared the extension to Cheltenham would result in a drop in revenue on the Beaumaris Sandringham section, others saw the potential for an increase in traffic from Cheltenham and Mentone by people travelling to the beach. Another participant who favoured the Cheltenham connection drew attention to the possibilities of ‘a round trip’ as in the days of the old horse trams, an attraction to tourists. [7] Advantages were also seen with the Cheltenham connection over one to Mentone in that there would be a saving in terms of fares and time taken to travel to Melbourne. [8]

When the Beaumaris Tramway Company with its horse drawn trams was first mooted in 1885, the plan proposed a three stage development. Stage one was the construction of the line from Bay Road, Sandringham to Balcombe Road; stage two was from Balcombe Road to Cromer Road; with the final section being from Cromer Road, Beaumaris to Mordialloc. This final section was never built. Although the company ceased service in 1915 there were residents of Mentone and Mordialloc who persisted with the dream of a tramway linking their suburbs to Sandringham. In 1922 the Surrey Hills – Mentone Tramways League was formed to facilitate the construction of lines along the length of Warrigal Road but it failed in its intention. [9] The Chairman of the Tramways Board ‘turned the idea down flat’ and the matter was dropped. Some years later a few people thought the time was opportune to raise the matter again. Cr Denyer from the fledgling City of Mordialloc attended with a deputation to the Tramways Board arguing for a tramway from Mentone to Oakleigh, although he said he did not care ‘two pence’ whether it went from Mentone or Mordialloc but he believed it would be of great benefit to the municipality. [10]

A meeting was convened in the Mordialloc Council Chambers March 25, 1929 of those people interested in securing a tramway from Box Hill to Mentone. Councillors Edwards, Denyer and Blanche of Mordialloc, and Clements, George, Stooke and Allnutt from Moorabbin were there along with the Minister of Railways, Frank Groves. Councillor Brine of Oakleigh said, “the project would provide work for many of those currently unemployed, the line would act as a feeder to two railway lines and would cause many people to build along the route. There were many people in the eastern districts who wanted direct access to the beach and should not be forced to go so far around as the present.” [11] The Moorabbin councillors when reporting to their colleagues were not so enthusiastic. Councillor Allnutt did not think it advisable to throw cold water on the proposition before they knew what the proposition meant. However he was quite aware that Oakleigh and Mordialloc would benefit the most and have the least to pay. [12] Mr Dickenson, a Mentone resident attending the meeting, took a much stronger position saying the Mentone people had nothing to gain as they had no desire to go to Oakleigh. He considered the ‘pioneer stage’ would be to go for a motor bus service.

Frank Groves, Minister of Railways, stressed that if the project was to eventuate there was a need to gather the appropriate data. Information on areas that would be served, where the line would act as a feeder, the area on which a betterment tax should be imposed, and estimate of the increased population as a result of the tramway were all matters that needed to be addressed. Guesswork was no good in a job of such magnitude, he warned. They would have to get facts. To this end Councillor Denyer moved that all present at the meeting form themselves into a league to be called the Box Hill to Mentone Tramway League to advance the cause. [13]

The Box Hill to Mentone tramway proposal like the Beaumaris to Cheltenham scheme did not eventuate. Over time it was the motor bus service that became the mode of public transport. Extensions to the tramway system from inner Melbourne occurred to the east and north but not to the south. There it was left to enterprises like the Ventura Company and the Grenda Company to meet the needs of an increasingly populous area.

Footnotes

- See Horse Trams from Cheltenham to Sandringham, Kingston Historical Web Site, http://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au

- Moorabbin News, July 28, 1928.

- Moorabbin News, July 21, 1928.

- Moorabbin News, July 28, 1928.

- Moorabbin News, July 28, 1928.

- Moorabbin News, July 28, 1928.

- For two shillings a person could purchase a ‘Circular Ticket’ and travel from Melbourne to Sandringham and from there by tram to Cheltenham, returning to town via Cheltenham.

- Moorabbin News, July 28, 1928.

- Gamble L., Mentone Through The Years, 2003, page 115.

- Moorabbin News, December 1, 1928.

- Moorabbin News,

- Moorabbin News April 27, 1929.

- Moorabbin News March 30, 1929.