Westfield Spans Nepean Highway

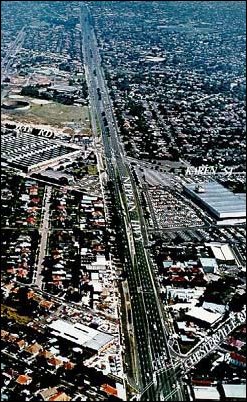

Aerial view of Southland Shopping Centre and Lucas Pty Ltd, Cheltenham, 1984.

Not everyone welcomed the news in 1992 that Westfield proposed to extend Southland across Nepean Highway on to the site of the failed Cheltenham Market. The Melbourne City Council opposed the development as a matter of principle as large freestanding regional retail and office complexes eroded the retail turnover and activity in the central business district. At the local level the Mordialloc Council warned its colleagues in the municipality of Moorabbin that, should the proposal proceed, financial hardship would be inflicted on the smaller shopping centres. [1] The Chelsea Council as well as local traders shared this view. “Local shopping strips would be forced to the wall and jobs would be lost”, was one view expressed. [2]

The Mentone Chamber of Commerce opposed the development as “Southland was already draining much activity from local shopping centres.” [3] Traders in Highett and Bentleigh vowed to fight the proposed expansion through legal means and government avenues. Eddie Belfield of Highett thought the Moorabbin councillors had sold traders out, but not all felt this way. [4] Mr Richards of Cheltenham said, “People only go to Southland under sufferance,” and Leon Hain of Patterson believed people would still shop locally because they liked individual attention, something that could not be provided in a large regional centre. For him the key threat to Southland’s development was other major shopping centres such as Chadstone.

Westfield developers began discussions with the Moorabbin Council in June 1991 about the rezoning of the Cheltenham market site to allow them to construct a $200 million extension. The plan was for a two level shopping centre, a ten-storied office complex and a retail bridge linking it to the existing Westfield Shopping Town on the eastern side of Nepean Highway. The new shopping centre was to include two department stores, one a discount supermarket, and the other a regular supermarket. A report in the Australian newspaper [5] said the project would rejuvenate the 24-year-old centre and place it in the big league of regional centres. Westfield went so far as to claim the developments would make Southland the largest retail shopping centre in Australia although competitors at Chadstone, Dandenong and Highpoint were already planning large expansions. [6]

Architect’s proposal for Southland Redevelopment superimposed on photograph, 1992.

Prior to the new developments Southland was already a major employer of labour with 2600 workers, of whom thirty percent were full time, fifty three percent casual and seventeen percent part-time. Of the 2600, seventy five percent were women and young people, with two thirds being under twenty five. In a Westfield analysis of the community benefits to be derived from the Southland extensions was the claim that the employment level would rise by 2100 for a loss of 100 positions in Moorabbin retail outlets. [7]

A consultant’s report prepared for Westfield noted that the venture would generate a net increase of retail sales of $108 million per annum, over and above the existing Southland/Cheltenham Market turnover, and of this sum $33 million would be drawn from local centres within the trading area. However, they argued that this impact was within the normal levels in a competitive market environment. [8] This loss of $33 million to local traders was seen by Cr Ian Lyons of Mordialloc as “nothing but greed by Southland”. [9]

Concerns were also expressed about the increase in traffic resulting from the Westfield expansion. The Public Transport Users’ Association predicted chaos, overcrowding and poor service unless the Public Transport Corporation created a new railway station to ease the situation. The Corporation, arguing the district was well served with bus routes and the presence of the Cheltenham railway station, dismissed the plea for the new facility. [10] Des Grogan, the consultant traffic engineer to Westfield acknowledged that an extra 8250 vehicles a day would be using the Nepean Highway and surrounding streets as a result of the development. However, the Moorabbin Council, VicRoads and Westfield agreed on road improvements, funded by Westfield through a $1.5 million community grant, to facilitate traffic movement. [11]

Geoff Leigh and Inga Peulich, members of the Legislative Assembly in the Victorian parliament representing the electorates of Mordialloc and Bentleigh, both declared their opposition to the bridge. Leigh saw it as “blot on the landscape” while Peulich described it as “an unattractive intrusion on the skyline.” [12] Leigh went on to indicate that his opposition would be less vehement if the linkage between the two portions of the centre was underground. Don Anderson, a consultant civil and landscape engineer, also canvassed this notion of a tunnel rather than a bridge. He believed the bridge, which amounted to the equivalent of a three-storey structure, would interrupt what he described as a magnificent vista created by Norfolk Island pines planted to the north and south of Southland. [13] There were other local residents who also expressed concern about overshadowing and the visual impact of the structure.

On the initiative of the Moorabbin Council an independent public enquiry was established to provide an opportunity for those people objecting to the development to present their arguments. Andrew McCutcheon, Planning Minister in the Victorian government, appointed Diane Morrison, Reg Ellis and Egils Stokans as a panel to consider the evidence presented by the 150 objectors and make recommendations. The panel’s challenge was to consider economic impact assessment reports, population projections, retail spending estimates, together with shadowing effects of the proposal and the merits of Norfolk Island pines, amongst other things, before drawing conclusions. [14]

Defending the Westfield proposal, its advocate pointed out that the bridge would enable the integration of the market site into Southland as a regional shopping centre, and it would improve safety for pedestrians and motorists by overcoming the physical barrier created by Nepean Highway. Furthermore, he said the bridge would provide a landmark at the entrance to the Cheltenham district and boost employment and economic activity in the bayside suburbs. The claim was that the bridge would create a unique gateway to the Cheltenham business centre. [15]

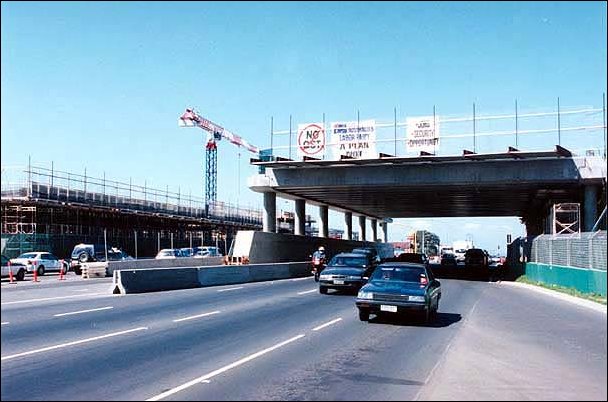

Bridge being constructed across Nepean Highway. 1998. Courtesy Leader Collection.

The enquiry panel met for eight weeks in the function room of the Moorabbin Council Chambers to hear submissions and after that time submitted its report to the Moorabbin Council on March 1, 1993. The initial reaction of the Council was to place an embargo on the release of the report until March 28, 1993 to allow time for its officers to respond to the recommendations. This action generated the headline “Secrecy shrouds Centre Extension” in the local newspaper. [16] Despite the embargo the newspaper was able to gain access and report the next week that the independent panel supported the proposal to extend Southland across Nepean Highway.

The three person panel in its report confirmed fears that some local traders would be unable to compete with the new development and some strip shops might be forced to close or relocate. Nevertheless, the report indicated that the benefits to the community as a whole greatly outweighed the detrimental effects on the nearby centres. The panel strongly supported the idea of a bridge link and should this aspect not proceed it considered the whole proposal should be reconsidered. [17]

While the mayor of Moorabbin, Cr Barry Neve, welcomed the recommendations of the enquiry’s report, commenting that he had always supported the extension, others expressed disappointment. Highett trader Eddie Belfield pointed out that 90 shops were already empty in a 5km radius of Southland and extending the shopping centre would ruin nearby businesses. He vowed to “fight this right to the bitter end.” Ralph Saulep representing the South East Combined Chambers of Commerce said his biggest concern was that

the decision would effectively hand over control of the future shopping requirements of the Moorabbin area to Westfield. [18] Alan Salter, a former councillor in the City of Moorabbin, wrote to the Moorabbin Standard to voice his opposition to the Westfield proposal pointing out the need to give consideration to the aged and the unemployed who easily become disenfranchised by things being too far away, expensive and time consuming to get to. Small viable local shopping centres, he suggested, had the spin-off benefit of attracting other businesses to the area. [19]

On June 1, 1993 Rob Maclellan, the Minister for Planning, gave approval for the Westfield $200 million development at Southland to proceed, noting that there is “plenty of evidence to show that a well managed strip centre with a niche market can perform well despite the proximity of large, free-standing retail complexes.” One aspect of the minister’s approval was that the expansion be substantially commenced by June 1997. [20]

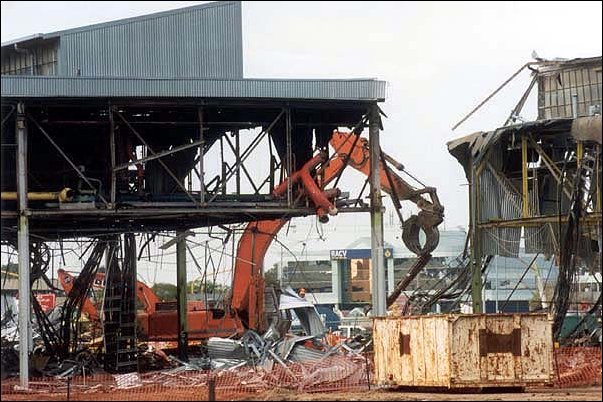

Clearing the old Cheltenham Market Site, 1998, Courtesy Leader Collection. Photographer Susan Windmiller.

In December 1996 the revised plan for the Southland Shopping Centre development was displayed showing the doubling of retail space, the addition of 1800 car spaces, a cinema complex of twenty screens and a bridge straddling Nepean Highway. [21] Because of discussion between the various interested parties considerable changes had been made to the plans originally submitted. The cinemas had been repositioned, the design of the façade had been modified and access to better parking arrangements improved.

Building in progress at Southland, 1998. Courtesy Leader Collection. Photographer Chris Eastman.

By November 1997 demolition of the Cheltenham Market site had commenced, and at that time it was expected the construction of the new shopping centre would be completed in two and a half years. In March the following year Jeff Kennett, the Premier of Victoria, poured the first concrete at the site and Steven Lowy, Westfield’s managing director said the project would be finished by the year 2000 creating 1800 jobs during construction and another 2000 retail jobs when completed. Cr Bill Nixon, the mayor of the City of Kingston said the development was of enormous value to the city and the Council would continue to liaise with Westfield during the construction to address residents’ concerns. [22]

Artist’s impression of the future Southland, 1998. Courtesy Leader Collection.

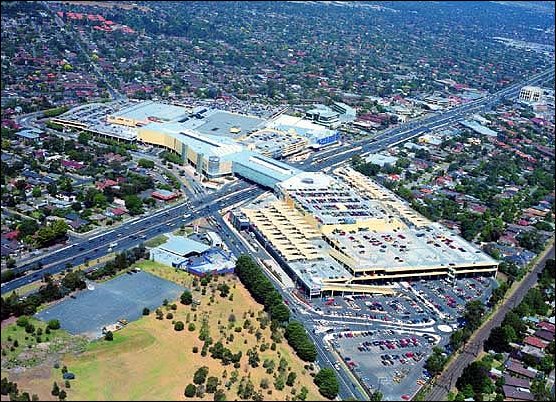

The prediction that the new Westfield Shopping Centre would be completed by 2000 was correct. In that year individual stores celebrated their opening with special sales to entice customers. Myer, Coles, K-mart, and Guyatt opened on the old market site, specialty shops and fast food outlet took their places on the bridge while the new retailer David Jones, Franklins and Big W were on the eastern location. Although some members of the district were fearful of the economic and social impact of this major shopping precinct there were others who saw it as an asset to the community. Only with the passage of time would the outcome be revealed.

Aerial view of Westfield 2000. Courtesy Westfield Management.

Footnotes

- Correspondence File – Moorabbin Council – February 2, 1992.

- Mordialloc News, February 26, 1992.

- Mordialloc News, February 19, 1992.

- Moorabbin News, January 15, 1992.

- Australian, January 18, 1992.

- Moorabbin News, December 18, 1991.

- Westfield Analysis of Community Benefits – Attachment, April 29, 1992.

- Henshall Hansen Associates, “Review of Southland/Cheltenham Market Proposed Expansion, April 1992.

- Moorabbin Standard, February 26, 1992.

- Southern Cross, October 21, 1992.

- Moorabbin Standard, November 17, 1992.

- Moorabbin Standard, November 17, 1992.

- Moorabbin Standard, December 1, 1992.

- Moorabbin Standard News, November 24, 1992.

- Moorabbin Standard, November 10, 1992.

- Moorabbin Standard, March 9, 1993.

- Moorabbin Standard, March 16, 1993.

- Moorabbin Standard, March 23, 1993.

- Moorabbin Standard, April 27, 1993.

- Moorabbin Standard, June 1, 1993.

- Moorabbin Standard, December 10, 1996.

- Moorabbin Standard, March 3, 1998.