Larrikins and Hooligans at Cheltenham

Vandalism and hooliganism are not just negative features of the twenty first century. Divisive elements of behaviour were present in the local district from early in the twentieth century and most likely earlier.

Tom Sheehy writing in 1977 reported the ‘warfare’ that occurred between young boys of the town and the local constable of police. [1] It was in reference to incidents after the 1904 unveiling of the Boer War Memorial on Point Nepean Road that Sheehy suggested the lads were attempting to emulate the activities of their returning local heroes from the conflict in South Africa. Apparently one member of the gang would create a disturbance to which the constable would respond. While he was attending to this commotion the remainder of the gang would pursue the destructive activity of white washing everything in sight. One solution seen by the older citizens was to establish a Boys’ Brigade where the lads could be suitably entertained and inculcated with appropriate values regarding the care of personal and community property. In addition, they hoped the boys might adopt the characteristics of ‘manly behaviour’. Cr Everest LePage observed that groups of young men, called ‘pushes’, were not uncommon throughout Melbourne in the early 1900s. According to him there was a Cheltenham push which called itself the Merry Hawks. [2]

Early in July 1905 a youth, who was amongst those who congregated at the Cheltenham Railway Station, was taken before the court and charged with using obscene language. It was his second offence so he was given a fine of £2 or the alternative of a one month term imprisonment. Two other cases of insulting behaviour were heard. Two ‘young roughs’ had refused to allow a young woman to pass. One, a second offender, was sentenced to one month in gaol or the payment of a £2 fine. The second youth was a first offender so his punishment was less. He was given a ten shilling fine or a stay of seven days in gaol. [3]

There were other examples of mischievous behaviour including deliberately leaving a garden gate open allowing a cow to enter, rude behaviour towards passengers on trains and damaging plants and shrubs at the Cheltenham railway station.

In August 1905 Dr Gerald Weigall, a local general practitioner, raised the issue of larrikinism and hooliganism at a meeting of the Cheltenham branch of the ANA (Australian Natives Association). He claimed women were not able to walk down the main street without being insulted by bands of young men and noted other anti-social behaviour occurring in the town. This behaviour he believed was not happening in Mentone and he wondered why. To counter this situation in Cheltenham he argued that young men should be provided with more useful and interesting occupations so as to keep them from loafing around the streets and getting into mischief. He saw it as appropriate for the society to give friendly advice and to tell the young men to desist from their idiotic behaviour. Dr Weigall went further and suggested the branch might form itself into a Vigilance Committee with the object of preventing damage being done to private property. [4]

Mr E Rippon agreed that something needed to be done about the hooliganism although he believed it was no worse at Cheltenham than in other places. He attributed the problem to the way mothers raised their children, perhaps implying the lack of discipline or a failure to instil appropriate standards of behaviour. Rippon did point out that some of the examples given by Dr Weigall of poor behaviour of the youth of Cheltenham were incorrect. For one example given by the doctor Rippon claimed the perpetrators were Sunday School children, not youths, and a second example of damage to insulators on light poles was due to severe weather; “the hoary visitor, Jack Frost” and not young men testing their skill and accuracy in throwing stones. [5]

Percy Colman, the president of the branch, thought some of the members were being too hard on the local lads. They were being blamed for things they did not do. He personally had not noticed any ladies being insulted as they walked in the street. Moreover, he believed there were some young girls who by their familiar remarks enticed the boys to speak to them with some degree of levity. Yet he did support the idea that some place should be provided where the lads could socialise and engage in ‘mental recreation’ and thus keep them away from street idling. [6

Responding to the report of the ANA meeting, “The Man in the Garden” defended the youth of the town stating that “hysterical abuse will do no good” and expressed his amusement in seeing a man raging over a paltry practical joke. While he did agree many of the boys were at the silly age, he suggested they were only as bad as other boys and no more. He was sure they would do good work like their brothers and comrades had done in South Africa and elsewhere. [7]

The meeting resolved to approach the Mechanics’ Institute’s Committee with a view of forming a young men’s club for “their mutual improvement and entertainment.” [8] This followed the information presented by Mr T Ricketts that he had brought the matter of larrikinism before the Institute’s committee where the idea of purchasing a billiard table was put forward, as well as providing other social and intellectual recreation for the young men of the town.

After making enquiries at other Mechanics’ Institutes about the success of billiard facilities the Cheltenham organization decided to proceed with the erection of a billiard room. To finance the building program the plan was to issue £1 debentures bearing interest at 5 per cent and redeemable by ballot. [9]

The president of the Institute, Cr LePage, approached Sir Thomas Bent, the Premier of the State, who was also a friend and a colleague on the Shire Council, and asked for financial assistance. At first the Premier promised £200 on condition that the Institute raised £100 but when it was found impossible to reach this target the condition was modified. [10] Finally Bent responded on behalf of the government with a grant of £200.

It was in June 1906 that Cr LePage reported that Sir Thomas was anxious for the money to be spent so it was important to clarify quickly what the Institute wanted to do. A meeting was called and a sub committee appointed to consider options. Their report, presented in June 23, 1906, recommended additions to the hall stage, the building of two retiring rooms and the construction of a billiard room. A billiard table was also to be purchased. [11]

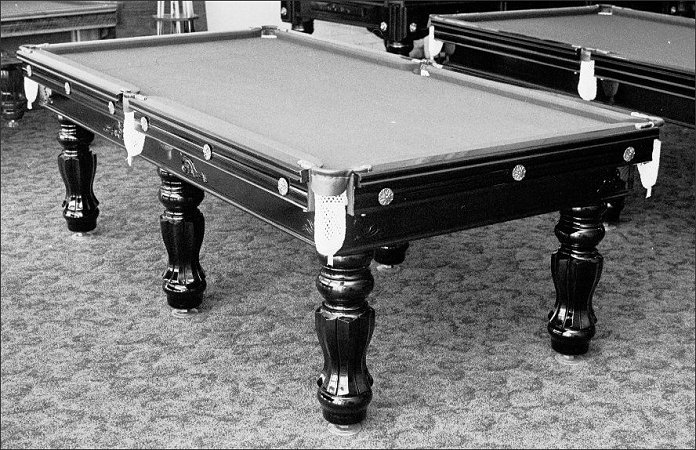

By September 1906, the Caudwell brothers of Mentone as contractors had made considerable progress in constructing the billiard room and plans were being made for the purchase of a billiard table. Initially the idea was to purchase a second-hand table but finally the decision was made to buy a new ‘up to date, full-size Fallshaw table’ at a cost of £75. [12]

An ‘Aster’ Billiard Table, 1983. Courtesy Leader Collection.

On December 4, 1906 the president of the Cheltenham Mechanics’ Institute, Cr LePage, officially opened the Institute’s additions to the acclaim of the invited audience who had earlier benefited from a ‘sumptuous tea’ provided by the president. The councillor ‘broke the balls’ scoring a nice cannon before the exhibition match between B Lambell and J Stewart commenced on the new table.

A local paper report praised Cr LePage’s actions in achieving the goal of a billiard room believing that there was no longer an excuse for the young men of Cheltenham to stand in the street to discuss cricket, football and other things for in the billiard room they had “a meeting place where they could while away their long winter evenings in a pleasant game of billiards or friendly intercourse.” The committee of members of the Institute were also very pleased with the outcome both from the point of view of a community and financial venture. Their president, Cr LePage, reported that eleven individuals had become members of the billiard room in the month since its opening. [13]

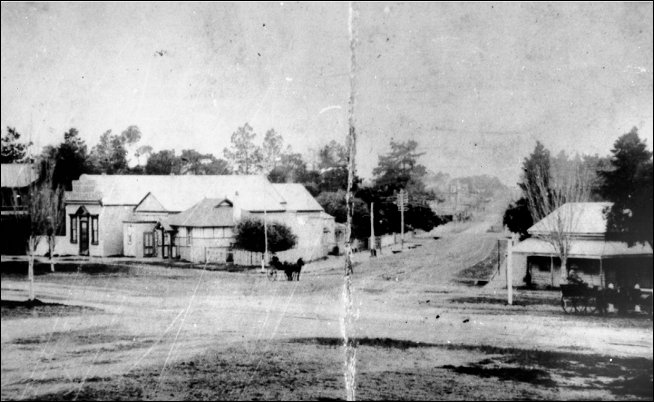

Intersection of Charman and Point Nepean roads with Billiard Hall to the left, c1906. Courtesy Eric Longmuir.

The relief from riotous and inappropriate behaviour of young men, brought about by the existence of the billiard room, if it ever existed, was short lived. Three years later the Moorabbin News was again protesting about the conduct of young people at Cheltenham but this time the anger was directed at visitors. The claim was that young girls, some about sixteen years of age, were wandering the streets half drunk. Residents instead of receiving the benefit of a cool breeze on a hot summer’s night, were compelled to remain indoors to escape from the abusive language uttered by the young women and men who came by train to Cheltenham on public holidays to dance at the Orderly Room on Point Nepean Road. [14]

Four months later the Moorabbin News was using forceful language to describe the ongoing problem of larrikinism, with terms such as “a horde of howling, drunken and depraved hooligans … a blot on civilized humanity …scourge of odious, depraved, disgusting and filthy imbeciles who defy law and order… residents are submitted to scenes that curdle the blood of the righteous and shock the modesty of the most hardened.” The writer was concerned about the impact of this behaviour on young children who might attempt to copy it and so be “caught up and swept down to ruin.” The cause of the problem he believed was the Violet Assembly, an organization who rented the Orderly Room to conduct a dance. However, approaches made to the hall authorities to withdraw access to the hall had been treated with nonchalance. The writer concluded his article with a call to residents “to unite and expunge from the town every drifter from the wreck of humanity that has hitherto demoralised it.” [15]

Comments about the youths creating nuisances in public places have persisted down to the present time. While many features of our society have changed, including levels of education, mobility of young people, strength of family life, job opportunities and the range of social and sporting activities available, there is still a small minority of youths and young people who have little respect for public and private property, and the rights of other people. Although authorities and motivated citizens have seen solutions in a variety of clubs where young people can spend their idle hours a final solution has yet to be found..

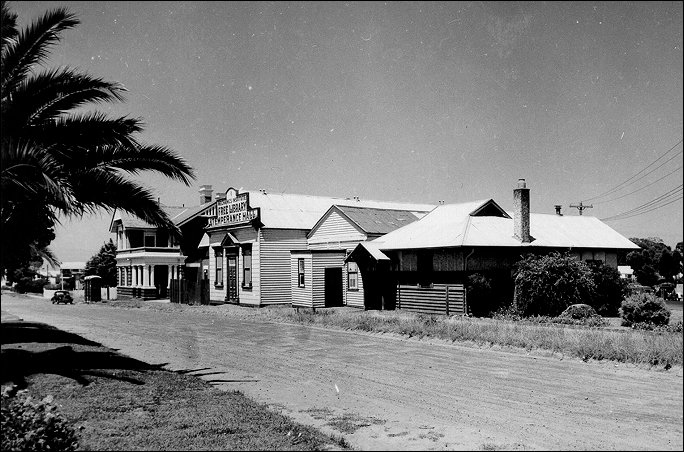

Billiard Hall and Mechanics Institute at Cheltenham, 1960. Courtesy Australian Post Archives.

Footnotes

- Moorabbin News, September 14, 1977.

- Moorabbin News, March 30, 1960.

- Moorabbin News, July 8, 1905.

- Moorabbin News, August 12, 1905.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Moorabbin News August 19, 1905.

- Moorabbin News August 26, 1905.

- Moorabbin News, September 16, 1905.

- Moorabbin News, December 8, 1906.

- Moorabbin News, June 23, 1906.

- Moorabbin News, November 10, 1906.

- Moorabbin News, January 12, 1907.

- Moorabbin News, January 1, 1910.

- Moorabbin News, April 2, 1910.