Bluey Lonsdale of Cheltenham

As you grow up there are people who impress you for a variety of reasons and remain in your memory for a long time. This may have been because of their achievements in sport, at school, or in business, or it may have been because of their personality, or their antics. According to Len Allnutt, Clarence Alexander (Bluey) Lonsdale was one of those people who made a lasting impression. Len claimed Bluey was a leader among the boys, a fine footballer and an individual who got up to tricks to the amusement of some, and anguish of others. He tells four stories of Bluey’s pranks. [1]

Len Allnutt, Storyteller, 2001. Courtesy Dorothy Allnutt.

Bluey Lonsdale was a ‘bit of a lad’ growing up in the small community of Cheltenham, at a time when everyone knew everyone else. It was in the 1930s and things were difficult for many families. The Great Depression had thrown many people out of work and some families relied on ‘sustenance’ to survive. A member of the family would go to the Shire Hall and register as an unemployed person and in return would be given food vouchers that would be honoured by local shopkeepers. The beneficiaries of this scheme were required to work on community projects for several days each week; such as unloading wood from railway trucks, chipping grass, constructing breakwaters and repairing roads. There were men who ‘took the swag’, moving around the country looking for part time work, picking fruit, trimming onions and a host of other manual and unskilled tasks. No money was available for entertainment so people made their own fun.

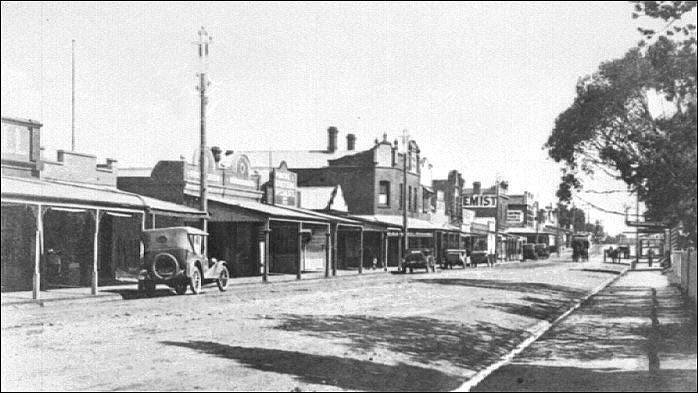

Charman Road, Cheltenham c1920. Courtesy Eric Longmuir.

Bluey’s father, George, was one of the local butchers. On one occasion Bluey was serving a woman in his father’s shop in Charman Road when he noticed the local dog catchers lassoing stray dogs and placing them in the cage on the back of a truck. The two dog catchers with their lassoes on the end of long poles were attempting to catch the last stray when it bolted off down Station Street. They went in pursuit.

Bluey finished serving his customer before taking a piece of meat out of the window and going outside to throw it in the gutter near the truck. He then unlatched the cage door and laughed as the dogs swarmed out probably attracted by the meat but also welcoming their freedom.

The dog catchers returned to the truck having failed to capture the last stray only to discover the cargo of animals had disappeared. How did they get out? That was the mystery to which Bluey never revealed the answer.

A second story that Len tells about Bluey involves a hearse, the special vehicle that was used to carry the body from the home, the church or the funeral parlour. The garage of the Cheltenham Funeral Directors was located behind the shops in Charman Road. One of the points of access was a bluestone paved lane which ran beside a billiard room, well patronised by some of the local lads and friends of Bluey. One day just before the hearse was to be driven out Bluey gained access to the glass sided vehicle without Wally Rose, the driver, being aware. Making himself comfortable in the back he lit up a cigarette as Wally drove off into Charman Road passing Bluey’s friends. They roared with laughter at the sight of Bluey and the smoke filled hearse. Wally, wondering what all the excitement was about, stopped the hearse and got out to investigate the cause of the fuss. Evicting Bluey from the hearse Wally informed him that he didn’t want to see him again, “not at least while you’re still alive”.

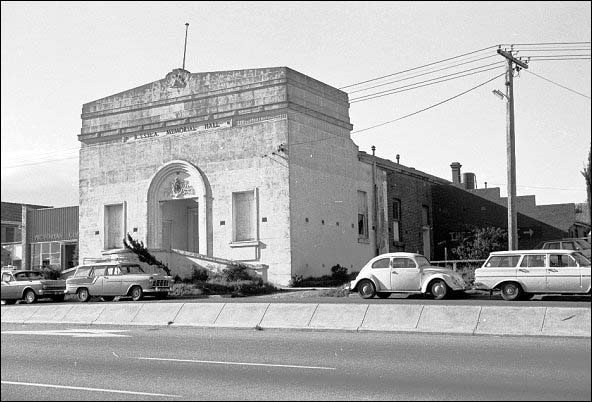

A third story involved Bluey at a dance in the Soldiers’ Hall on Point Nepean Road. During the Depression not all young men could afford to pay the admission price to a dance. One night Bluey with two friends was outside the hall when he asked them to give him a leg up onto the sill of an open window. Once settled, he commenced shouting abuse to friends who were dancing around the floor of the hall. Unbeknown to Bluey, Constable Thomas, the local policeman, saw him and taking hold of the rascal’s leg started to pull him from his perch on the window sill. Bluey’s friends ‘scarped’ on the first sighting of the police constable. Bluey, thinking it was one of his mates trying to dislodge him, retaliated with a few kicks, telling his tormenter that if he didn’t let go he would punch him in the face. Constable Thomas, in turn, used his baton to inflict some punishing blows on Bluey’s body to the extent that Bluey was off the streets for a few days. Constable Thomas’s attitude was there was no point in throwing the young men of the district into goal and taking them to court for minor offences as no one had any money to pay fines, so the best approach to misdemeanours was ‘a kick up the behind’, commented Len. Bluey’s mates thought it the best night’s entertainment they had had for a long time.

Soldiers’ Memorial Hall, Cheltenham, 1973. Courtesy Eric Longmuir.

A fourth story told about Bluey occurred on a Friday night when the shops in Cheltenham remained open until nine o’clock. It involved another young man who played football in the local team, although not very well. Often he didn’t get a game but he was a ‘smartly dressed show off’ who Bluey thought should be ‘pulled down a peg or two’.

Bluey enlisted the aid of three friends to whom he explained his plan. Two were directed to hide behind tombstones half way up the drive of the Cheltenham cemetery, but to create a lot of ghostly noises when he and the ‘smart alec’ approached. Bluey then went with his third accomplice who lived at the back of the cemetery, into the town to lay the trap.

To his co-conspirator and in the presence of the smartly dressed show off, Bluey said, “I don’t know how you do it walking through the cemetery at night to get home. I won’t do it. I reckon there are ghosts up there.” He turned to the skite and goaded him with the question, “You wouldn’t do it would you? You’re not game!” Immediately and without much thought, as Bluey predicted, the confident young man replied, “Of course I would”. “Well come on let’s do it,” said Bluey drawing the collaborator in as a witness. “I want you as a witness because I don’t think he will do it.”

Graves in the Pioneers’ Cemetery, Cheltenham.

The three of them were walking up the dark unlit drive of the cemetery when Bluey claimed he could hear voices. His two companions said they heard nothing. Bluey followed it up by pointing to the right of the drive indicating that he saw movement. At that moment the two hiding mates jumped out shouting and screaming. Bluey yelled out ‘Ghosts, go for your life’ and scampered down the drive to Charman road. The bragger left for dead tried to follow but in the darkness fell into an open grave and called out to Bluey , “Don’t leave me.” Bluey and his mate returned and pulled him out of the grave chiding him, “You useless fool, I knew you couldn’t do it.” Len Allnutt said the story of the prank quickly spread around the town and the boaster never lived it down.

Bluey, who started playing football with the Cheltenham Club played League football at Hawthorn where, according to Len Allnutt, he was one of the best half-backs in the League in the 1930s. On October 29, 1942 he joined the army at Glenhuntly when he was 45 years of age, and at the time of his discharge on November 2, 1945 was a member of the 14/32 Australian Infantry Battalion. [2] Returning to civilian life he took up residence in Moe, Victoria, where he worked as a plasterer. It was in Moe that he died in 1971 at 65 years of age. [3]

Footnotes

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Len Allnutt, 2002.

- World War II Website – http://www.ww2roll.gov.au

- Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages.