The Mordialloc Baby Murders

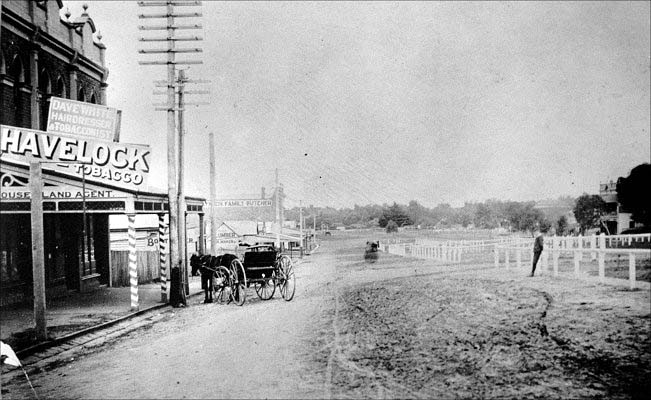

Main Street, Mordialloc, c1910. Courtesy Hazel Pierce.

On December 5, 1913 two detectives from Melbourne, Sainsbury and Olholm, travelled by train to Mordialloc and caught a cab to a lonely house out past Epsom racecourse. It was located on a small farm along a bush track in what was then sparsely settled country over two miles from the small seaside township. Their visit was to result in a sensational death and some grisly discoveries that put shock, fear and disgust into the lives of Mordialloc people.

The two detectives had gone to the country property in Mordialloc’s backblocks because they were investigating the disappearance of a number of babies from various places in inner Melbourne suburbs. Police work led them to the home of the Newmans which was on the track that later became Malcolm Road, now part of an industrial estate. At the time the area was divided into small farms, each of about ten acres, stretching inland towards the Dandenongs. The Newmans lived in a weatherboard house on one of these, called La Belle Farm. Isabella Newman and her husband, Thomas, had a family of five but only two lived at home, a boy seventeen and another who was eleven. The others had left home, one daughter having married.

Neighbours of the Newmans regarded them as unexceptional people who had few visitors and who rarely visited local people. Thomas Newman grew oats and other crops and worked as a labourer in the district. Isabella often chatted to local children when she met them going to school and she had helped at least one neighbour when her children were sick. The woman reported that Mrs Newman had stayed at night and helped nurse her young ones through a severe bout of pneumonia and fever. Other women found her helpful, especially where assistance with children was required, but apart from these connections local people knew little about the Newmans who had been in Mordialloc for a number of years. They revealed few details about their own lives to others in the district

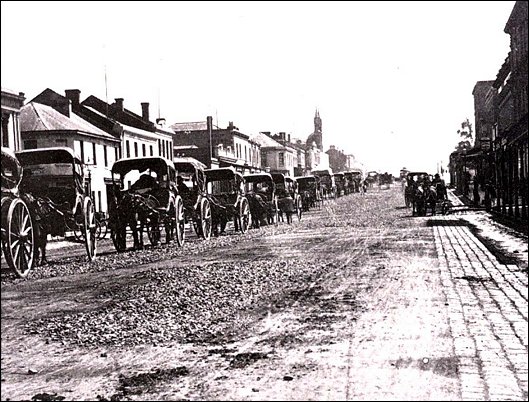

There was one unusual aspect of Isabella Newman’s life that drew comment from several people. Almost daily she went to the city by train and returned each night, often quite late. Thus she became acquainted with some of the cabbies who carried passengers to and from the Mordialloc railway station. On these trips she always carried a dress basket covered over with fabric and one cabbie had carried the basket into the house on a couple of occasions, noting that it was quite heavy. Mrs Newman had remarked that it was full of groceries. The cab driver said that he had been well paid by Isabella and had received as much as seven shillings for the trip from Mordialloc station, well above the few shillings of the normal fare.

Cabs lined up in Melbourne street, c1900.

When Detectives Sainsbury and Olholm called at La Belle Farm on Friday 5th December 1913 they carried a warrant for the arrest of Isabella Newman resulting from a long period of police work, some of which dated back to 1909. They began to question the Mordialloc woman over babies that had disappeared.

The police had been alerted by many complaints during the past year from women who had given up infants for adoption or fostering. In some cases they had answered advertisements in the press where a ‘Mrs Williams’ or a ‘Mrs Millar’ had offered to take babies for adoption and promised that they would be lovingly cared for. The woman who said she was ‘Mrs Williams’ or ‘Mrs Millar’ claimed to be acting on her own behalf or sometimes as an intermediary for someone wanting to adopt a child. When young mothers contacted her she gave them details of land she owned at Frankston and the fact that her husband was insured for 500 pounds, as well as her ownership of racehorses. This, she said, would enable her to go into business if ever she became a widow so the baby being adopted would be well looked after. She made a fuss of the babies and small children when they were presented to her, and as noted earlier, seemed to have a natural affinity with youngsters. Young mothers were asked to dress the babies in their best clothes when being offered for ‘looking after’, giving a nice feeling about this woman’s love for the infants she was taking. Police had been told that this ‘Williams’ or ‘Millar’ woman sought payment for the service of adopting each child. Various amounts were quoted. In one case it was 50 pounds and another it was 12 pounds to be paid over a twenty-four-week period.

In several cases the young mothers were told their babies would be brought for a ‘visit’ periodically and meeting places were arranged, but the woman seldom came good on these promises and the babies did not see their mothers again. Several of the young mothers, no doubt guilt-ridden and heartbroken, became suspicious and in one case that was to be crucial. A young Fitzroy mother had met ‘Mrs Williams’ and after allowing her baby to be ‘adopted’ had asked that the baby be brought back to Fitzroy after one month for a visit. ‘Mrs Williams’ attended the house of the young mother’s sister where the meeting was to take place, but she had no baby with her. After a dispute the sister of the aggrieved young mother insisted that the baby be produced and ‘Mrs Williams’ offered to take her to where the baby was being looked after. The pair went to Mordialloc where the indignant aunt of the missing infant was shown a baby being cared for by a neighbour of ‘Mrs Williams’. The Fitzroy woman pointed out that the baby was not her sister’s; for one thing it was a female, and her sister had ‘adopted out’ a boy. ‘Mrs Williams’ was adamant that the child was the one from Fitzroy but the visiting woman threatened to go to the police if her sister’s baby was not produced. She left Mordialloc not satisfied with the promises made and police were notified. In any case the police had already become alarmed when the corpses of several infants were discovered in parks or behind hedges in the Prahran-St Kilda district. Reports began to appear in the Melbourne dailies about ‘infanticide’in the inner suburbs.

It should be remembered that at this time there were many young women who were in despair because of unwanted pregnancies. Contraception methods were not as effective as they are now. Single mothers were often treated as outcasts. Families commonly disowned daughters who had ‘fallen’ and the best they could expect was to be sent to an institution, quite often run by religious orders, where they would stay until they had the baby adopted. For many young single mothers this course was not possible and they were forced into more drastic actions. The newspaper advertisements of ‘Mrs Williams’ attracted many replies.

Police, using information given by those who answered baby advertisements, traced the woman known as ‘Mrs Williams’ to an address in Charlotte Place, St Kilda, where she had stayed for a short time. It so happened that this address was the same as Isabella Newman’s married daughter. The woman claiming to be ‘Mrs Williams’ had used another address in Perth Street, Prahran, as well. Further checking of police files revealed that Mrs Isabella Newman had been charged in 1909 with receiving an infant for adoption without signing the appropriate documents, a fact that may have gone unnoticed except that the illegitimate child from Geelong had disappeared without trace. The court had fined her five pounds but the conviction was quashed after an appeal. Isabella Newman had convinced the court that she had no knowledge of the child’s fate as the infant had been placed in the care of others who could not be found.

With this background information fresh in their minds the two detectives began to question Mrs Newman on that day early in December after she had let them in to her modestly furnished lounge room. Isabella Newman refused to answer many of the questions put to her and denied having anything to do with adopting babies. When the two men noticed a baby in a pram in another room Mrs Newman claimed it was her daughter’s child that she was caring for temporarily. One of the detectives opened a wardrobe and found it full of baby clothes, enough for ten infants, he estimated. This tallied with later statements by neighbours that there were often large amounts of washing on Mrs Newman’s clothes line. Then came the sensational event that shocked Melbourne citizens and put an unwelcome focus on Mordialloc.

Isabella, who had been informed she was about to be arrested and taken to the city for further questioning, asked the detectives to allow her time in her bedroom to change into another dress. They permitted her to leave the lounge, but after a short time a scream of agony came from behind the bedroom door. As the policemen entered that room they found Mrs Newman writhing in pain on the bed. She had swallowed strychnine. They carried her outside to the cab that had brought the detectives to the house. The cabbie whipped the horse into a gallop as the vehicle tore down the gravel track that is now White Street and then into the town to find Dr Grindrod, the sole Mordialloc medical practitioner. After a short examination he pronounced the woman dead.

This did not end the sensational series of events. When the police returned to the farm their discoveries rocked the little community and sent shock waves through Melbourne. On that fateful day the other members of Isabella Newman’s family had their lives immersed in turmoil. The teenager son, who was working at home on that day, and one of his sisters who was contacted, were held by police for questioning. Then in the afternoon the eleven-year-old schoolboy arrived home to learn that his mother was dead in gruesome circumstances and that no one would be allowed to stay at La Belle Farm that night. In tears he was taken to a neighbour’s house to be given some solace. Thomas Newman arrived home from work to be given the terrible news of his wife’s violent death. Later he, with his sons and daughters, had to undergo extended questioning by the detectives who had now informed headquarters and been reinforced with more police.

More shocks were to follow. On the day after Isabella’s death police combed through La Belle Farm, digging up much of the ground near the house and searching sheds. It was not long before they dug up the decaying remains of two babies, a boy and a girl, in the dirt floor of the fowl shed. Despite more intense searches of the property no other bodies were found, but later a baby’s corpse was found at Carrum beach and was linked to Mrs Newman. Police contacted one young mother who had recently given up her baby to Mrs Newman and escorted her from South Melbourne to Mordialloc. Here she was shown the infant that had been in the house on the day Isabella committed suicide. She fondled the child and expressed relief that no harm had come to it, vowing never to let anyone take her baby away again.

When the news of these events broke in the days following Isabella’s death, Mordialloc people were dumbfounded and some were frightened. As police raked through the evidence at La Belle Farm during those early December days, many women in the district refused to stay in their homes alone during the day, and certainly not at night. Some arranged to go to neighbours’ places while their men were at work. The grisly discoveries brought an eerie uneasiness to the community.

There was no satisfactory explanation or conclusion to the sad tale. Isabel Newman, in the desperate last moments of her life, used a writing pad in her bedroom to send her family a brief message before taking the lethal poison dose that she had concealed in her blouse. Her note read:

My dear husband and children—Forgive me for what I have done. I am innocent but things seem against me. God forgive me and help you in your hour of trial—Your loving wife and mother. The last word; My husband and children do not know anything, but that I am getting 10/- per week to look after baby. That is all they know, so help me God – (signed) I. Newman

The Melbourne papers printed daily accounts of the Mordialloc ‘baby farming’, as they termed it, for about a week. They gave details about the culprit. Isabella Newman had been a footrunner when she was young and had competed under the name of ‘Isa Bell’. When one considers that she was 47 at the time of her death it is apparent that her ‘pedestrian’ events were probably in the 1880s, a time when few women would have been so liberated. Other accounts told of how handsome she was as a young woman. No one will ever know what drove her to the monstrous activity that took over her life in her last years. Her husband intimated that she had looked after a baby when they had lived in St Kilda for a short time, some months before the tragedy. But he said that his wife was doing that for a friend and to earn some money. He said that she had some debts at that time. He also stated that she sometimes worked as a house cleaner and took in washing to earn extra cash, but he gave the impression he was not fully aware of all his wife’s dealings. ‘How could she have deceived me?’ was one reaction he expressed to police.

It seems obvious that Isabella Newman needed money badly and the babies met their fate because she could receive substantial sums for taking them from their natural mothers. There was little evidence to show what Isabella did with the money. She probably frittered it away on little luxuries, like the generous payments to cabbies, all of whom now knew what had sometimes been in the large heavy dress basket that she always had with her. It is possible that she had some other dark secret in her life that led to her ruin. Mental instability may have been a major factor, though the evidence given by everyone who knew her pointed to the fact that she appeared to be normal. She covered up her fiendish activity very well. Her own family, subjected to heavy police interrogation, seem to have been unaware of her double life.

The coroner quickly concluded that her death was by suicide and that she had murdered three babies, the two found at Mordialloc and the one at Carrum beach. It seems likely that she had killed others, probably by smothering them. How many unfortunate infants met their deaths through Isabella Newman’s machinations will never be known. Young girls who had ‘adopted out’ their babies would not always speak out for all sorts of reasons. But there were enough who did come forward to indicate that Isabella’s plausible business methods had dealt out death to more than the three children noted in the official report.