William McKnight: Soldier and Resident of Cheltenham

Major William McKnight, c1920.

William McKnight was the son of James and Mary (Miller). His parents came to Port Phillip Bay from England in 1851. After a short stay in Melbourne the family moved to Cheltenham to take up residence in a tent on a property located on what is now the southern corner of Swinden Street and Nepean Highway. At that time James and Mary McKnight were amongst the first Europeans to settle in a district described as ‘wild’ in a report written in 1902. [1].

William was born in 1853 at the Cheltenham property and later five more children were born there. James, the second child was born in 1857, Isabella 1859, George Mathew 1861, and Mary Ann 1864. Like his brothers and sisters, William McKnight was a pupil at the Cheltenham State School, No 84 in Charman Road. There his attendance is recorded as the first entry on an honour board noting distinguished students.

After leaving school William McKnight worked as a market gardener while becoming involved in community affairs. For seventeen years he was associated with the Market Gardeners’ Picnic Committee and from an early age was a member of the Cheltenham Mechanics’ Institute. [2] Later he served as a trustee of the Institute, retiring in 1931 to make way for the nomination of a younger person. [3] He was a founding member of Branch 40 of the Protestant Alliance Friendly Society and rose to the position of Grand Master of the Grand PAFS Lodge of Victoria.

Another interest of William was the militia. He was a member of the 2nd Battalion Militia Infantry at Brighton along with Robert Rigg and when Rigg was given approval to form a company of rangers at Cheltenham by Major Otter, William McKnight joined him. As a lieutenant McKnight assisted in the organization of meetings at Cheltenham, Bentleigh, Moorabbin, Somerville and Mornington in order to recruit members for the new company. It was in 1889 that the first detachment of ‘G” Company commenced drilling at the Mordialloc State School where Rigg was the head teacher. By 1891 Rigg had been promoted to major and William McKnight held the rank of captain in the new company known as the Cheltenham Rangers. [4]

With the conflict between Britain and the Boers in South Africa many Victorians volunteered for service. Several members of the Cheltenham Rangers were part of this group. William McKnight, aged forty six was one of these. He offered to forgo his status as an officer and join the First Contingent as a private. However he was not accepted until the Third Contingent or Bushmen’s Corp was formed and transported to the Cape of Good Hope in 1900. His success on this occasion in achieving his goal of joining the British and colonial forces in South Africa was due to the influence of his colonel who supported his application. [5]

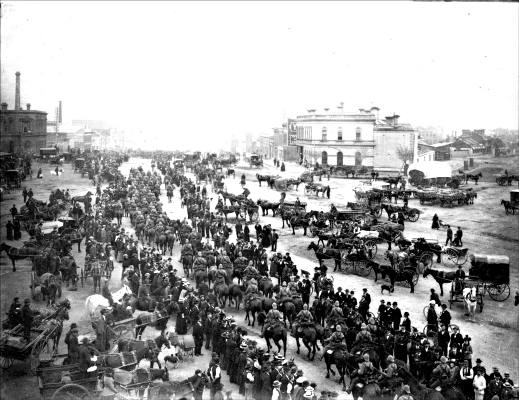

Leaving for South Africa.

Before leaving for South Africa William McKnight was given a farewell by the local community and colleagues in the Rangers and Militia in the Protestant Hall at Cheltenham on March 1, 1900. Cr Mills who chaired the meeting of about one hundred men said that all who knew him held McKnight in the highest esteem. Mills wished McKnight well hoping he would win the Victoria Cross and he was sure the captain would do his duty like a Britisher. [6] They presented him with 47 sovereigns and an illuminated address from the numerous societies to which he belonged and from the general public. Initially members of the organising committee were going to provide him with a horse but changed their minds when they discovered the horse would become the property of the crown.

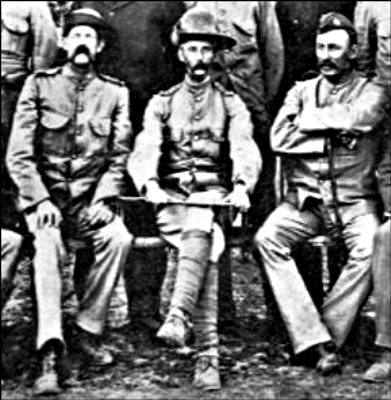

In South Africa William McKnight served in several different capacities. At first with the Bushmen he held the position of adjutant with the rank of captain but during this early period of service he spent several months as Paymaster, Camp Quarter Master and Officer in Command at a Base Camp as well as active service in the field. [7]. He then joined Colonel Otter in the Fifth Contingent at Pretoria with the rank of major. Otter had been his commanding officer in the Victorian Rangers. [8]

Colonel Otter with two other officers.

On June 12, 1901 William McKnight was a member of a column in eastern Transvaal under the command of Major General Beatson. The Victorians had been split into two wings, one of which was commanded by Major Morris a British officer. The senior Victorian officer in this wing was Major McKnight. They had camped for the night when the Boers infiltrated their lines. Havoc was created with fourteen Victorians dead, and about sixty wounded. Seventy nine horses and about twenty mules were killed. The Boers losses were ten killed and about thirty wounded.

Those Who Died.

General Beatson was scathing in his comments about the actions of the Victorian troopers and William McKnight was dismissed from his command although he was not blamed by his troops for the devastating defeat.

On returning from South Africa Major McKnight and men previously members of the Ranger company were welcomed home at the orderly room on Point Nepean Road, Cheltenham. Colonel Otter, William McKnight’s commanding officer and a guest for the occasion spoke of his regard for William and his qualities as an officer. Colonel Rodd in proposing a toast to McKnight commented on his sterling qualities as a civilian and soldier and said all ranks acknowledged him to be “a real white man.” [9]

William McKnight in responding to the praise of his senior officers said it was strange that such a receptions should be given to a man who had been called “a white livered cur,” by a senior British officer in South Africa. Despite this verbal attack on him, William acknowledged that the English officers taken as a whole were a fine lot of fellows. He went on to praise the members of the Fifth Contingent as a body of men that could not be bettered. It was unfortunate, he believed, that an English officer from India who did not know the Australians took command, and men were treated as dogs and their clothes taken from them, and the severe losses the Fifth Contingent had sustained were due to carelessness. [10]

William McKnight in a report requested by Major General Downes, the commandant of the Victorian Military Forces, and subsequently passed to the Secretary of Defence and the Prime Minister, detailed his recollection of events at Wilmanrust. [11] . He wrote of the confusion amongst his company when the Boers infiltrated their camp dressed in a similar fashion to the Victorians, in khaki and wearing hats with the brim turned up. While attempting to achieve some order out of the confusion he was wounded twice and taken prisoner. Ten minutes later, on being released to attend to the wounded he found Major Morris the commanding officer had surrendered.

After arrival at Middleberg, a few weeks after the disaster at Wilmanrust, McKnight was told that General Beatson, the officer in command of the British forces called the 5th VMR “a fat-arsed pot-bellied, lazy lot of wasters” to which he added “a white-livered lot of curs”. When Beatson heard that McKnight had “got his back up” sent an officer with an apology but McKnight refused to accept it. “It was too late – that the statement had become public property and was the talk of the Camp” [12] Major Umphelby, McKnight’s senior officer did accept the General’s apology and this information was conveyed to the troops by McKnight causing some unrest amongst the members of the Fifth Contingent.

McKnight in his report expressed his opinion that gross carelessness had been shown in the column and lives had been thrown away when there was no occasion for it. He said the men felt that there was no regard shown for their lives and in some cases the punishments awarded were of a most humiliating character. While loyal to General Beatson, when the good reputation of the Victorians was challenged McKnight said he felt compelled to strongly protest against the general’s universal condemnation of the men. Although he wrote that General Beatson was “quite satisfied with the work I had done” McKnight acknowledged that the general thought him “too outspoken”.

Major General Downes in his note attached to McKnight’s report wrote that as General Beatson had apologized for his words and as the commander of the Fifth VMR had accepted it nothing could be done. Nevertheless, he queried whether an officer who uses “such contemptible and disgusting language to and of troops under his command is fitted to have command of men.”

In the year following his return from South Africa, at forty-nine years of age, William McKnight married Isabella McColl at the Presbyterian Church at Canterbury. The event was reported in the Moorabbin News giving details of the participants and guests together with the gifts they gave to the married couple – dessert knives and forks, salad bowl and rosewood chair, brush and comb, laced table centre, cushion and supper cloth; candlestick, photo frame and vases. William gave his bride a pearl spray brooch while she in return gave him a dressing case. They travelled to Sydney for their honeymoon before taking up residence at Belgrave.[13]

Isabella died before William whose death occurred on April 16, 1934 after a prolonged illness when he was a resident in a private hospital. The funeral service took place at the home of William’s brother George McKnight in Cheltenham and the property where he was born. He was buried in the Presbyterian portion of the Cheltenham Pioneers; Cemetery where the graveside service was conducted by the Rev J E Higginbotham who was a minister at the Cheltenham Presbyterian Church thirty years earlier. William McKnight was 80 years of age. Two sons, William Duncan and Hugh McColl were left to mourn their loss. [14]

Memorial in St Kilda Road to members of the Fifth Victorian contingent who served in South Africa.

Footnotes

- Moorabbin News, August 16, 1902.

- Brighton Southern Cross, February 24, 1900.

- Moorabbin News, April 21, 1934.

- Brighton Southern Cross, January 5, 1901.

- Brighton Southern Cross, March 3, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross, March 3, 1900.

- Brighton Southern Cross , November 24, 1900.

- Moorabbin News, April 13, 1901.

- Moorabbin News, November 2, 1901.

- Moorabbin News, November 2, 1901.

- See Article http//localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au Wilmansrust: The Debacle in South Africa Article Reference 185

- Report from Major McKnight to Major General Downes, National Archives of Australia Series B168/0, Item 1901/3859.

- Moorabbin News, July 19, 1902.

- Moorabbin News, April 21, 1934.