Sand Mining

Mining at Karkarook Park, 1998. Courtesy Leader Collection.

The dunes, which ran along the perimeter of Port Phillip Bay from Cheltenham to Frankston and as far inland as Heatherton, Clayton and further east, have provided a resource for sand mining for over a hundred years. The various grades of sand found were used in the construction of major Melbourne buildings and in the manufacture of glass.

Frank McGuire wrote that one factor that facilitated the development of the sand mining in the area was the opening of the Caulfield to Frankston railway line in 1882 (The section to Mordialloc was formally opened the previous year). Several sidings were created along the line. The Wedge family had a railway siding located towards Frankston in 1890 from where sand was transported to Melbourne from their estate [1] There were other railway sidings between Frankston and Mordialloc where mined sand was loaded for delivery to Melbourne. [2] The Australian Glass Company used the Forsyth siding to transport sand they were mining from their property on the northern bank of the Patterson River. In 1934 the Construction Sand Ltd had sand pits in East Frankston with a 500 metre rail link to the main line. [3]

Ken Smith recalled that when he was a young boy living in Cheltenham in the 1920s the heavily laden sand trains often needed assistance to conquer the steep gradient of the line between Mentone and Cheltenham. “Steam engines hauled fifteen to twenty trucks of sand daily to Melbourne in the afternoons about 4 o’clock. Often the engine failed to make the grade between Mentone and Cheltenham, the steepest section of the Frankston-Flinders Street railway line. Many, many times the engine failed to make the grade near Latrobe Street. In those days, the trains had a shunter or guard in a guard’s van at the end of each train. He would disconnect half the train allowing the engine to haul those trucks up the hill and back them into the siding on the western side of the station. The engine would then go back and haul the remainder of the train to the siding. Even then the trains crawled at a slow pace up the hill towards Bay Road. Electric trains came around 1923 and when the sand train stalled the electric train would gently help it up the hill. It would then be put in a siding to allow electric trains quicker access to Melbourne.” [4]

It was the Crawfords who established a sand pit at Cheltenham in the 1920s in the area now known as Shipton Reserve at the rear of the Cheltenham Primary School. “They shovelled sand into drays for transport to the railway station at the goods rail siding located on the eastern side of the railway just north of Park Road. The horse-drawn carts had an extra horse to help the dray through the loose sandy track from the pit to Glebe Avenue where the golf links are today. The extra horse was left to return by itself. The drays wended their way down Glebe Avenue, Charman and Park roads to the siding where the sand was shovelled into trucks. Rather exhausting work, especially in the summer time. Crawfords attempted to have an extension of the goods line through the park to the pit, but failed. Eventually Crawfords sold out to a Mr Chevasse who continued operating the pit until the area was depleted of suitable sand.” [5]

By the early 1930s sand was being mined at Clayton, Heatherton and other places in addition to Cheltenham and places beyond Mordialloc. The initial concern of the Moorabbin Shire council was not the disfigurement of the landscape or what to do with the hole created, but rather with the damage being done to roads by the heavy wagons and speeding trucks. [6] Residents were also concerned about the dust that was created by the mining activity.

Four owners of properties mining sand in Clayton in 1934 agreed to pay sums of money to the council to repair the roads and offered metal screenings to facilitate the work. R Dingle, O Gilpin Ltd and V M Whitchurch each paid £12 10/ while Reynolds Bros Cartage Co with a much smaller business contributed £5. [7]

By 1935 the council was becoming more concerned about the operation of the sand mining companies and consideration began to be given to constraining their operation within the municipality. The cartage of sand on some roads was prohibited for certain periods of time. For example, Old Dandenong Road, Heatherton, was closed for three months to the cartage of sand and portions of Bernard Street, Cheltenham, were closed to the same activity for six months. [8] The by-laws committee of the council began deliberations on whether restrictions should be placed on owners and entrepreneurs wishing to mine sand from private property. The council had power under the Local Government Act 1928 regarding land use, to prescribe areas within the municipality as residential and prohibit those areas being used for industrial purposes, including the removal of sand. In addition, they could fix levels below which sand could not be removed for building or other purposes. The committee members realised the issue was controversial but decided to recommend to council that appropriate by-laws be formed and implemented to control sand mining in the municipality of Moorabbin. [9]

At an October 1935 council meeting details of the proposed bylaw were examined. It was suggested that a pre-eminent requirement of anyone wishing to remove sand was the gaining of a licence. [10] The fee suggested was one penny for every cubic foot of sand to be removed, and in addition, a deposit of one shilling per cubic yard was to be paid in advance of removal as a safeguard to a proprietor leaving the property in an unsatisfactory condition or walking away from his obligations once the sand had been removed. The deposit money was to be placed in trust and used to restore the land to a suitable condition. Should there be any money remaining it was to be returned to the licensee, but if more money was required this would be the responsibility of the licensee.

Not all councillors were in favour of pressing ahead with the by-law. Cr Wishart wanted the matter deferred until the question of charges was discussed with the pit owners as through discussion, he believed, a solution could be found that was acceptable to the council, owners and ratepayers. Cr Bevers wanted the proposal to ‘lie on the table’ for further consideration but the Mayor (Cr George) argued that any further delay was dangerous and as a great deal of time had already been spent by the committee framing the regulations it was time for the matter to proceed. Finally it was resolved to form a committee of four councillors to confer with four representatives of the Sandpits Proprietors’ Association and to hold a conference in the municipal buildings with the interested parties. [11] [12]

A W Adams, a sandpit owner of Cavanagh Street, Cheltenham aware of the actions of the council, and the recently formed progress association’s antagonistic attitude to pits, wrote to the editor of the Moorabbin News expressing the view that sand pits were not an unnecessary evil forced upon ratepayers as portrayed by some, but rather a new essential industry opening up avenues of employment in the municipality. Land that had been relatively worthless and never been productive was bringing families into the district because of employment opportunities in the pits and these families in turn were spending money with local trades people, thus boosting the general prosperity of the district. Additional transport was needed to shift the sand and the trucks purchased needed to be serviced at local garages, once again enhancing employment opportunities. These factors Adams saw as evidence that the pits justified their existence. [13]

Adams’ views were challenged by C J Hoffman of the Cheltenham Progress Association, in a following edition of the Moorabbin News. [14] He bemoaned the presence of uncontrolled conditions, which he believed made the pits an “unnecessary evil” and called the industry a nuisance and a menace to the district as a whole. Hoffman believed the pit owners were arguing for a control-free industry and posed the rhetorical question, “If a man has sand on his property why should he not remove it?” and then went on to answer it by drawing parallels to a person wishing to build a fowl house or keep pigs. They needed council approval so why not pit owners?

At the meeting of the pit owners’ association, held with the council on December 4, it was admitted that while fifty per cent of the association’s members agreed to some form of control there was no guarantee that the remainder would fall into line. They believed they had certain rights which they were not prepared to surrender. After taking into consideration the replacing of over-burden, the profit margin was small so the association asked the council not to charge a licence fee or to introduce by-laws regulating the removal of sand from private property. However, Mr Brough, from the association, indicated that the majority of members were prepared to pay a nominal annual registration fee and that owners operating below road level should deposit a reasonable sum of money as a guarantee of good faith that the land would be satisfactorily drained. However, Mr Coulter of Moorabbin Sand Pty Ltd had legal advice suggesting the council had no power to charge a fee for a licence to operate a sand pit, arguing that the removal of sand does not come within the interpretation of the words “quarrying operations.” [15]

Residents and organizations continued to complain about the sand pits. A H Sutherland of Clarinda objected to the establishment of sand pits on land in Stuart Road. The valuation of his land, he claimed, had depreciated to such an extent that he was unable to sell. The Victoria Golf Club protested against the council’s action in permitting the cartage of sand on Park Road, Cheltenham and the committee of management of the Heatherton Sanatorium urged the Council to prohibit the creation of any further pits as the dust caused by the present operations was seriously affecting the health of its patients. [16] A resident, Mr Brown, went so far as to accuse the council of corruption in a very abusive letter which on the motion of Cr Allnutt was ‘not received’ and placed in the waste paper basket. [17] Another correspondent offered to provide board and lodging free for one month to any member of the council who would live on Clayton Road given its deplorable condition resulting from the cartage of sand. The writer signed himself/herself, “Sprained Ankle.” [18]

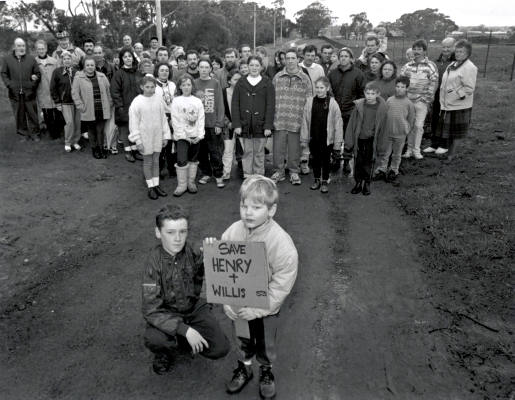

Luke O’Brien and Ryan Mahony with local residents protesting against proposal to sell streets for sand mining, 1995. Courtesy Leader Collection.

By July 1936, and after months of discussion, the council finally passed a by-law related to the removal of rock, stone, gravel, clay and sand from residential areas. A licence was essential and would be issued in appropriate cases on the payment of a fee of £5 5/- where the area involved was less than one acre. Larger areas would attract a higher fee. Licences could be refused. Drainage levels were to be fixed by council and guarantees had to be given by proprietors to fill the excavations within a specified time. [19] By September the Public Works Department indicated the bylaw had been approved.

Several pit owners immediately applied for licences. T G Johnson of Bernard Street, Cheltenham; Hartnett Bros of Keys Road, Moorabbin; and S Cuddigan of Avoca Street, Highett, were granted work permits for a two year period while applications from M Adams on the corner of Argus and Cavanagh Streets; C Williams, Wickham Road and A W Smith of Heather Grove, Cheltenham, were deferred to allow ward councillors to inspect them. S F Lancaster pleaded that the regulations did not apply to his pit in Crawford Street, Cheltenham because its operation commenced prior to January 4, 1911. The council recognised his claim. [20]

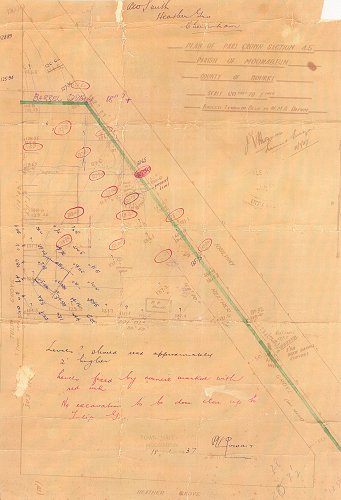

Plan for sand mining at Heather Grove, Cheltenham 1937. Courtesy Ken Smith.

By November 1937 council was becoming impatient with pit owners who were operating without a licence, or were working portions of their property which were not included in the licence, or were failing to honour agreements on filling and restoration. Mr Chevasse’s request to operate a sand pit in Tulip Grove was refused because of earlier failings. The application of E Nelson and Co Pty to remove sand from their property in Heatherton Road and to install a small washing plant on the land lapsed from lack of support in council. Cr Sheppard, in stating that he was against granting any more licences, pointed out that the holes in the workings will never be filled up and the land will become absolutely worthless as it would be too flat and low to build upon. [21]

In 1941 the Moorabbin Council received applications from four property owners for authorization to excavate 178 acres of land. These four owners were confident of success as the council had earlier given approval to A E Hocking to work 40 acres in Old Dandenong Road. J McGrath, the managing director of McGrath Sand and Stone Co Pty Ltd, congratulated the council on its change of attitude to the sand business and informed the councillors his company had “taken no time in acquiring new properties knowing full well that you are a body of fair-minded men and will treat all applications in the same fashion.” McGrath applied to excavate eight acres on the corner of Keys and Moorabbin roads which he planned to fill with municipal garbage where sludge was unsuitable. He estimated it would take ten years to complete the operation. At the same time as making this application McGrath also applied for a permit for thirty six acres adjoining the eight acres, and another one hundred acres in Kingston Road opposite the Kingston Heath Golf Links. [22]

Despite McGrath’s expectations the council refused his application. Cr Caldwell expressed surprise of the extent to which the municipality was being dug about, mutilated and scarred. In speaking against the application of T M Mardling to remove sand from thirty four acres in Carroll Road, Clarinda, Cr George said the Moorabbin Ward was looking like a battlefield and despite assurances that the pits will be filled in, he thought they would always exist. “We get very vague promises and the Ward is becoming an eye-sore, not a thing of beauty.” [23]

Sand pits and market gardens in Moorabbin District, c2000.

The problems associated with sand mining did not disappear in the late 40s and early 50s although the frequency with which they were reported in local newspapers significantly reduced. Other more pressing issues in the eyes of the residents and ratepayers emerged. A large number of young families were moving into the municipality to set up their homes in situations where sewerage did not exist and where reticulated water was not always available. [24] Access to homes was severely restricted as roads were often quagmires in winter and sand traps in summer. Kindergartens and baby health centres were few in number. Given these circumstances, the attention of the councillors changed and the heat in the sand mining debate diminished for a time only to re-emerge later with a change of focus. The early nineties saw debate once again on sand mining but now it related to mining public land, the rehabilitation of old quarry sites and the establishment of a chain of parks. This is a continuing, but another, story.

Footnotes

- McGuire, Mordialloc Chelsea News, July 1, 1981.

- McGuire, Chelsea a Beachside Community, 1985 page45.

- Moorabbin News, March 31, 1934.

- Whitehead, G., Interview with Ken Smith, 2003.

- Smith, K., Memories of Cheltenham, 2003 [Manuscript].

- Moorabbin News, September 14, 1935.

- Moorabbin News, July 7, 1934.

- Moorabbin News, August 17, 1935.

- Moorabbin News August 31,1935.

- Moorabbin News, October 19, 1935.

- The committee was made up of Cr George from the Moorabbin Ward, Cr Butters, North Ward; Cr Allnutt, Cheltenham Ward; and Cr Forbes, Centre Ward.

- Moorabbin News, November 30, 1935.

- Moorabbin News, December 7, 1935.

- Moorabbin News, December 21, 1935.

- Moorabbin News, January 4, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, March 21, 1936.

- Moorabbin News August 6, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, September 5, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, July 4, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, December 12, 1936.

- Moorabbin News, November 20, 1937.

- Moorabbin News, May 9, 1941.

- Moorabbin News, May 9, 1941.

- In April 1950 the Mayor of Moorabbin, Cr L Coates reported that 1700 permits for houses had been issued in the previous twelve months, double the number of any other council Moorabbin News, April 6, 1950.