The Mentone Board of Works: 1887-1892

This was a different ‘Board of Works’ from what we usually understand by the term. This Mentone entity which began in the 1880s had little in common with the huge organisation, ‘Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works’, that controlled water supply and city planning for most of the twentieth century until renamed ‘Melbourne Water’. What, then, was the Mentone Board of Works? Why would a small seaside town of the 1880s have a ‘Board of Works’? Here is why.

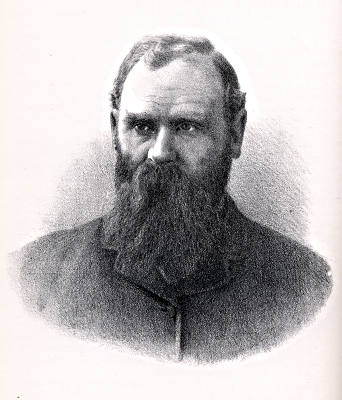

Mentone came into being after 1883. It was set up to be a fashionable watering place, a desirable seaside resort where people of means might buy land and establish holiday homes or permanent places of abode. Matthew Davies, a Victorian lawyer, politician and ‘land boomer’, was the prime mover in establishing the town on land that had been mainly pastures and scrub owned by Alexander Balcombe and his family until 1882 when Davies acquired it. Davies grew in social stature through the 1880s, being elected to the Victorian Parliament and rising to the position of Speaker at the end if the decade. By that time he was the head of about forty interlocked companies which speculated in land and property development. Matthew Davies, after drawing up plans for the new town of Mentone, formed various companies which sold the land around his subdivision, and gave the place Mediterranean street names so that it would assume a Riviera aura. This worked quite well for a time and some big homes were built, along with facilities such as the Mentone Coffee Palace (now Kilbreda), a racecourse, a sea baths, a skating rink and a public hall. Land sales went well too until the late eighties when the first cool whiffs heralded the coming cold winds of the economic depression that brought despair in the 1890s.

Matthew Davies.

Davies and a number of his ambitious land boom colleagues of the mid-eighties were clever enough to see that a town would attract land purchasers if it offered the amenities and infrastructure that allowed a comfortable lifestyle in keeping with the standards of the times. They built many of these using their own companies. But they believed that more could be done if the resources of governments and other citizens could be harnessed. The Mentone land boomers, led by Matthew Davies and Joseph Bartlett Davies, who was a principal in some of his younger brother’s companies, hit upon the idea of a formal lobby group that could be used to exert pressure for the improvement of the town’s physical amenities. They formed a body that was given the impressive name, ‘Mentone Board of Works’.

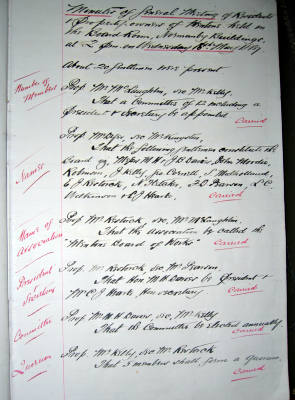

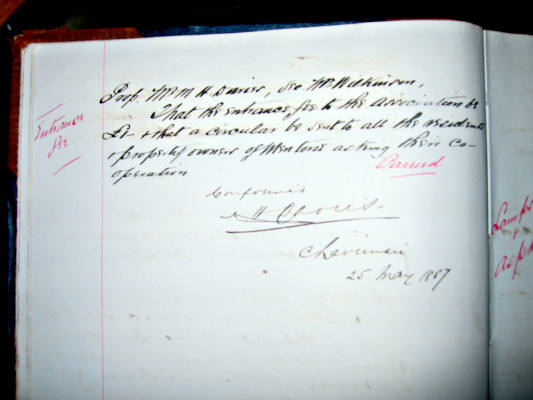

The inaugural meeting of this entity was held on Wednesday, 18th May 1887, at 2 p.m. in the Board Room, Normanby Buildings, Chancery Lane, Melbourne. This location was Matthew Davies’ city offices in Little Collins Street to the west of Elizabeth Street. The meetings took place there for the first two years, after which they were more frequently held at Mentone in the Coffee Palace or at the Recreation Hall located in the park near the corner of Venice Street and Mentone Parade. The first meeting was described as a gathering of ‘property owners and residents of Mentone’ and ‘about 20 gentlemen were present’. The meeting proceeded to elect M.H. Davies as president and C.J.Hearle as honorary secretary, with a committee of another ten members ( Messrs J.B.Davies, John Moodie, Robinson, Kelly, Cornell, Mulholland, Restorck, Fletcher, Pearson and Wilkinson.). At the ensuing meetings of 1887 several new members were admitted, including C.J. Potts, who acted as chairman at times, as well as Messrs Kekwick, Nicholls, Gladstone and Shackell. Matthew Davies proposed that the entrance fee for members of the Board be one pound and that all Mentone residents be sent a circular to encourage them to join. The group did not nominate any aims or objectives at the first meeting. It seems that their purpose in meeting was implicitly understood, for at following meetings, held fortnightly, they launched into immediate practical action. Sub-committees were formed and went to work.

Normanby House 2002. Courtesy Graham Whitehead.

Within the fortnight before the second meeting the committee had met and decided to order 12 gas lamps to be erected in Mentone’s principal streets. At the second meeting, as well as confirming this, the Board delegated various members to take action on several matters. The Postmaster General was to be asked about terms and conditions required for a telegraph office in Mentone; two members had to organise a petition among residents to push for a State School in the town; the Railway Commissioner had pressure on him from Mentone to run the first morning train beyond East Brighton so workers at Mentone’s many construction jobs could get to work; and enquiries were to be made about hiring a cab driver with a waggonette to carry patrons from the railway station to the baths down past the end of Mentone Parade.

Mentone was a new town and its physical terrain was rough. Roads were unsealed tracks. Footpaths were hazardous, uncomfortably muddy or dusty depending on the weather, that is where they existed at all. The new Board tackled this problem straight away. In its first weeks the Board ensured that was done to fill a huge hole that made the footpath access to the jetty dangerous. At that time a small pier existed at the bottom of the cliffs near the end of Mentone Parade. It was later the site of a new sea baths. This jetty was so small that the Board petitioned the Customs Ministry to have it lengthened, but this was refused. Board members also requested help from the Moorabbin Shire in having Mentone Parade asphalted. Within a few months the Shire agreed to pay half the cost of the asphalt strip up to a limit of 200 pounds.

More work on the town’s physical appearance and amenity followed. Within the first year of the Mentone Board’s formation a tree-planting program had begun after consultation with the Department of Agriculture. It seems that trees planted in the early stages of the program often died and in 1890-1 the Board had a very big additional planting project with several hundred trees being established. In Mentone Parade they reported planting Chichester Elms and plane trees, while on each side of the railway line silver poplars were put in. (In the station car park there are silver poplars still growing today, having survived the lopping of the original trees in the 1970s by means of suckers sent up by the old tree roots ).

Much of the Board’s energy in its first few years was spent on the water supply problem. Mentone had no reticulated water. Mentone Board applied to the Victorian Board of Land and Works for extension of water mains to the new town. The Government body replied that it had no power to supply reticulated water beyond a ten-mile radius from the GPO in Melbourne. South Road, Moorabbin, was about the southern limit. Despite the lobbying of John Keys, MP, there was no immediate prospect of mains water. The Mentone Board hired contractors to sink a bore and satisfy the need from artesian supplies. It should be remembered that rainwater tanks were the only supply and during hot dry periods the situation often became desperate. The Board later had to order water to be delivered by rail during drought periods, with residents paying by the gallon. Throughout 1888-9 the Austral-American Boring Company had a contract with the Mentone Board to drill for water in Mentone at a location near the Recreation Reserve. The work began amid great optimism. The Board even considered an offer to build a 20,000 gallon tank near the bore but delayed the decision because the cost was 500 pounds and the Mentone Board already had a debt of 300 pounds. At first the results were promising and water was pumped at a sufficient rate. The Board even began to set prices to be charged for the water. The bore went down below 500 feet but then the quality of the water declined and government analysts declared it ‘unfavourable’. Despite receiving a 250 pound grant from the Victorian Government and help from the Shire, the Mentone Board had a debt of more than 200 pounds over the project and later received threatening letters from the contractors over non-payment. Eventually, an overdraft from the bank (one of Davies’ companies) allowed settlement. The bore was closed for a time, but in the early 1890s there were plans to re-open it so water could be used for street and gutter flushing. Little came of that idea as the economic troubles of the nineties dried up funds.

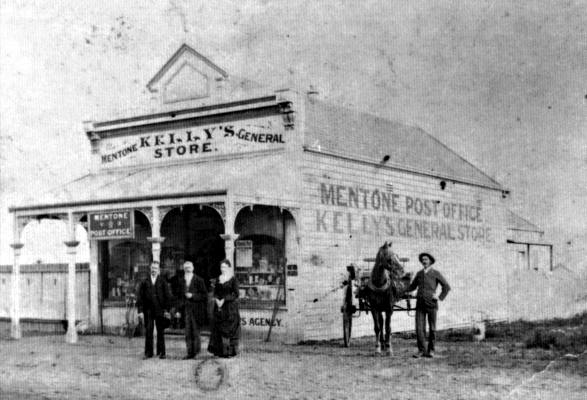

The Mentone Board of Works had more success in other matters. The telegraph office was opened in March, 1888. Mrs Kelly, the postmistress, ran the telegraph service which required delivery of messages within a radius of one and a half miles. It was located in Kelly’s general store opposite the station in Como Parade West not far from Balcombe Road. (Today the site has a large liquor store.) By 1890 the post office and telegraph service had moved to a new brick office in Mentone Parade at the rear of the Coffee Palace. It operated there for only a couple of years as the financial stringency of the 1892-3 period saw it taken back to another store, Thomas’s fruit shop opposite the railway station. Presumably the government pruned the service and would not pay rent on the brick building that had appeared. It was on Coffee Palace land so Davies missed out on rent revenue. The building eventually became part of the Brigidine Convent campus in 1904.

Kelly’s General Store, Mentone, c1887. Courtesy Damian Smith.

Perhaps the most successful lobbying was that concerning the primary school. The Mentone Board from its first meeting began collecting signatures on a petition for a government school, as well as numbers of children who would attend. In November 1888 Mentone lobbyists claimed there were 138 children eligible to attend the school, but received a letter from the Education Minister stating that its inspector had ‘been around and reported only about 60’. The Board stepped up the pressure, sending in actual names of prospective pupils and organising deputations to the Minister. They even talked to the Mentone Recreation Company about providing the Recreation Hall as a temporary classroom for students while construction of the school went on. The lobbying paid off. In March, 1889, the Government decided to establish a Mentone school and agreed to its opening in April of that year in the Recreation Hall. The new school went up in Childers Street, the authorities having rejected an offer of another site where the lawn bowling club now exists. On the occasion of the official opening of the new school in October, 1889, the Mentone Board invited the Minister of Education, Dr Pearson, to a luncheon at the Coffee Palace and provided for the ‘school children to be given a tea’. Just a year later the Board was again arranging temporary classrooms in the Recreation Hall as the red brick school was extended to house a growth in the student population.

Mentone Recreation Hall, c1920. Courtesy Mordialloc and District Historical Society.

Mentone Board of Works had other successes. Despite the failure to have the original small jetty extended they managed to have the Victorian Government build a new pier at the bottom of Naples Road in 1891. In April, 1890, members of the Mentone Board managed to have the Minister for Customs, Mr Patterson, visit Mentone and inspect the beachfront sites that would be suitable for a pier. Board members put their arguments to Patterson directly after having been introduced by John Keys, the local Member of Parliament. Patterson agreed to ask that a sum of money be placed on the estimates and in February, 1891, tenders were called for the erection of the new jetty. The pier extended about 900 feet into the bay and had an L-shaped section at the end to serve as a potential docking area for steamers. At the time boating in the bay was popular among Mentone people and the old jetty near the end of Mentone Parade did not serve them well, as it did not jut out far enough to reach deep water for boats to pull alongside. The new pier was an asset which was destined to last until the 1960s and the Board of Works claimed credit for its erection.

At the other end of the beach the old baths fell into disrepair and a new baths structure went up in 1891, erected by The Mentone Baths Company, allowing the contractors to use the pile driver on two bay contracts in the same period. Mentone’s new baths were considered to be up with the best around the bay at this time. There was a large enclosed swimming area, diving board, dressing sheds and a kiosk. The ‘new baths’ building occupied the prime piece of beachfront below the cliffs near Mentone Hotel, also built at this time. The Board of Works welcomed the move and paid some of the cost to renovate the ‘old baths’ at the bottom of Warrigal Road. These were designated as ‘The Ladies’ Baths’, because at that time the sexes were forbidden to bathe in the sea together. In a few years the ladies complained about their inferior venue and a system of alternate times in the ‘new baths’ was introduced. When the red flag was up men were swimming; a white flag meant that men had to stay away while the ladies were in the water.

Mentone Board of Works busied itself with many practical matters concerning the town’s appearance and comfort. Many meetings discussed how to drain the swampy areas and the streets; complaints were rife about nightsoil dumping around the town’s outskirts; foot crossings over the railway were improved after Board lobbying; clifftop paths became a reality; lamps were placed in many more public places. The board entertained the dream of a railway line from Sandringham through Mentone to Dandenong in 1889, something that was never to occur despite serious meetings pushing the idea. The Board was in favour of a Mentone newspaper. The Mentone and District Chronicle did appear for a few years from 1889, but it is not clear how the Board was involved. Certainly its members would have been in close contact with the paper’s editors and probably offered financial support as well.

In assessing the importance of the Board of Works it is fair to say that the body played an important role in Mentone’s early development. The town’s infrastructure, as explained above, was put in place more quickly due to Board influence. Government ears at Moorabbin Shire and in Spring Street, Melbourne, were alerted constantly to the needs of Mentone. The Board’s members included members of parliament and councillors. The Board openly canvassed the support of its own members for election to Shire Council. The fact that Mentone was converted from grazing paddocks to a town with many facilities in less than a decade is at least partly due to Mentone’s official lobby group. This group included some wealthy men and many who knew how to apply pressure for money and resources.

Page from Minute Book of Board listing members and Name of Board, May 18, 1887. Courtesy Mordialloc & District Historical Society.

Money helped the Board to its successes, but in the end it was the foolish belief by Board members and others that the supply of money was inexhaustible that brought the activities of Mentone Board to an end. Originally, the Mentone Board members paid a small annual subscription of one pound or one guinea. That, of course, did not go far in financing the work they pursued. The Board worked by getting companies, business proprietors and property owners in the district to contribute to their schemes. They were able to do this because of the clout that many Board personalities had. Matthew Davies was in parliament, so was Shackell, another member. Then there were solicitors such as C.J.Potts, real estate men like C.H.Hearle, and many business owners as well as other professionals. John Moodie and Joseph Davies, wealthy land boomers, together with Charles Figgis, an architect, are other examples. Early on, the Board was able to convince people to contribute funds for the work of building Mentone. Large amounts came from the Davies land companies. When the water bore was being funded the Mentone Land Company and several other like bodies contributed 200 pounds. The Board exhorted locals to pay subscriptions and support its work. Another way funds came in was through fees charged. During the building boom the Mentone Board of Works asked builders to pay five pounds for smaller houses and greater sums for big edifices. However, the Board’s most important source of funds lay in its ability to influence governments to allocate money to Mentone projects. The political ability, knowledge of the system, and the social standing of these Mentone people counted greatly in getting decisions in their favour. The amounts were often large. Mentone pier cost 1800 pounds. Would it have been built if the Mentone lobbyists had not been around?

Matthew Davies, as Chairman, signs minutes of previous meeting of Board as being confirmed. Courtesy Mordialloc and District Historical Society.

They did not always get their way. When the Mentone Parade asphalt was about to be laid in 1887 the Board wrote to C.H.James whose property, Bleak House, was at the beach end of the proposed asphalt road near the old baths. They wanted his help with funding the project. James, who was one of the wealthiest of the land boomers at that time, wrote back and told them he would not give anything!

The Mentone Board of Works disappeared from the scene in 1892. The minute book does not record any formal disbanding, though those proceedings may have been recorded elsewhere. There had been rumblings earlier within the Board. At various times the minutes record the failure of members to attend meetings and even as early as February, 1889, a discussion was held about the ‘desirability of winding up the business of the Board’. This was about the time that Sir Matthew Davies resigned as a member, presumably because his work as Speaker in the Victorian Parliament was absorbing his energies. This is to say nothing of the difficulties his many interlocked investment companies were about to run into. Davies continued his financial support, although his donation of four pounds for tree planting seems modest when matched by earlier largesse he distributed in Mentone. There was evidence in the minute book that the Board did not meet for several months early in 1890, so it was not all plain sailing. By 1890 the accounts show the receipt and dispersal of about 81 pounds during the year, a large fall from the 300 or so in the first year it operated. The Board seems to have been downsizing its activities a little by the early 1890s. Even so, some Mentone people remained active until 1892. The Board continued to attract new members for in its final year the names Cowan, Caudwell, Obbinson Ward, Barnett, Groom and Webster are listed as attending meetings. Charles Figgis, the architect who designed the Mentone Hotel, chaired some of the meetings in the last months.

What probably happened in July, 1892, when the last minutes are recorded, is that the terrible financial crisis that hit Melbourne brought an end to the work that the Board could pursue. Businesses were bankrupted, banks were shutting their doors, people were literally starving for lack of employment and the community’s morale had sunk to levels so low that people were in despair. In a climate like that a Board of Works pushing for projects that could be defined as ‘extras’ seemed out of place.