The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum Comes to Cheltenham

The beginnings of the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum were made before Victoria gained its independence from New South Wales in 1851. Councillor John Smith, of the City of Melbourne requested government officers in Sydney on June 1, 1848 to grant a site and the necessary finance to build an institution where the ill and destitute of Melbourne could be cared for. But it was not until 1850 that the foundation stone of the building to be erected in North Melbourne was laid by Superintendent La Trobe. Governor FitzRoy in Sydney granted the site together with a sum of £1000 on the understanding that an equal sum of money would be raised by public subscription. [1]

The Argus described the ten acre site in North Melbourne bound by Abbotsford, Elm, Curzon and Miller Streets as “…the most magnificent that could well be imagined, the view being not only most extensive, and beautiful in the extreme, but peculiarly eligible for a public building, from the fact of its commanding every entrance to the city, North, South, East and West, as well as forming a most prominent object of observation from the Bay. [2] Another contemporary report provides further insight into the nature of the site; “One of the problems encountered was that the Asylum was out in the bush and there was no firm thoroughfare of any kind leading to it. As it was mid winter, to save visitors from bogging or drowning, an avenue was buoyed at intervals one each side with rude torches fastened to poles secured in the ground and soldiers and every policeman that could be spared patrolled the bush track from the junction of the Queen and LaTrobe Streets between Flagstaff Hill and the Cemetery, to act as pilots for the carriages.” [3]

It was architect Charles Laing who gained the commission to design an imposing public building while builders Charles Brown, Henry Brown and Samuel Ramsden were given the task of constructing it. Their initial tender was for £2850 although the cost of the finished building was £3272-19-6. [4]

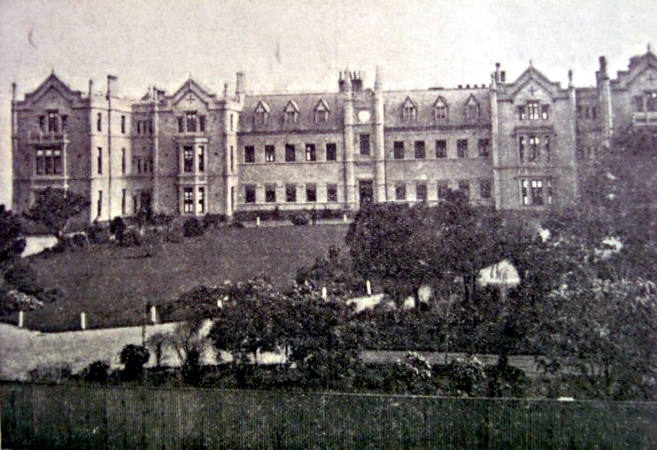

Melbourne Benevolent Asylum, North Melbourne, 1900.

The discovery of gold in Victoria brought an unprecedented influx of people who sought to make their fortune. Unfortunately large numbers failed, and many individuals becoming destitute and ill turned to the asylum for help. This placed great pressure on the available accommodation so, over a period of twenty years, a series of extensions were made to the original building. By 1865 the committee was renting adjoining premises to accommodate some of the inmates.

In 1875 the Superintendent and Secretary of the Benevolent Asylum, James McCutcheon, argued in the annual report that the city site was too limiting and was no longer appropriate because of its proximity to a crowded city where an outbreak of an epidemic would be dangerous for their old and feeble inmates. He wanted a government grant of land 100 to 200 acres in size in a location at least ten miles from the city and near a railway station. The new buildings he envisaged would be no more than two storeys high to facilitate movement and be designed to completely separate male and female inmates. McCutcheon saw the less convenient location an advantage in that access would be more difficult causing fewer applications for admittance. [5]

In 1880 a special appeal was launched to raise money claiming the Asylum was “filled to repletion with aged and infirm persons, many of them labouring under complicated diseases, and all fit and worthy objects for charitable sympathy; whilst every week numbers of gaunt, hungry and distressed persons, of both sexes, crowd the passages, and vainly implore admission.”[6] It was at this time that a deputation met with the Premier requesting a land grant of 150 acres at Cheltenham. Although sympathetically heard by the Premier it was not for some years that the issue was addressed. [7]

In 1887 J E Thomas, the secretary to the Premier, wrote to the Asylum committee suggesting they might consider a site at Frankston for the building of a new refuge. He reported that the Lands Department believed a location on the railway line had several advantages including good climate, excellent soil and a splendid view. There were upwards of 3000 acres available and a portion, he wrote, could be granted to the committee for the construction of buildings and the development of flower gardens by the inmates. Flowers and shrubs grown there, as well as decorating the institution, could also be offered for sale. The Lands Department acknowledged that the Cheltenham site was suitable for present needs but believed that in a few years similar objections to those raised against the North Melbourne site would be received. Reservations were also expressed in the letter about the financial provisions for the new buildings. Estimates of building cost had not been obtained and reliable estimates of the value of the North Melbourne property and the amount of money likely to be realised from its sale were not known. [8]

When the details of the Premier’s response, delivered through his secretary, were published in The Age newspaper the Rev Alfred Caffin, vicar of St Matthew’s Church of England in Cheltenham, replied with surprise and indignation. “The Lands Department apparently can see much further into the future than the residents of this locality, who are anxious to have the new building erected in their midst. The Lands Department, without showing the imaginary grounds for objection that may be raised in the future, then generously offer a site at Frankston.” Caffin goes on to point out that the features of the Frankston site equally apply to the proposed Cheltenham location, although he acknowledges the Frankston location might be a little grander of view. Caffin suggested that if the authorities were after a view then a site at Dromana would perhaps suit better. Cheltenham had the advantage of being closer to the city and had a permanent water source necessary for the production of flowers and shrubs. Perhaps, Caffin conjectures, the Lands Department is interested in one of the Frankston Brick Companies or some powerful outside influence has brought to bear its sway on the government. [9]

The Asylum committee thought the Frankston location was too far away but J M Smith saw the opportunity to take advantage of the government’s offer. Given the enormous expense and great trouble that would be incurred in transferring the institution to another site he proposed to his colleagues that they should ask the government to endow the charity with the 3000 acres of land at Frankston. When the idea was challenged by several of his colleagues as being unrealistic he replied, “the Government don’t know what to do with it. They have no use for it.” [10] Mr Gillies, the Premier of Victoria, replied to the committee’s communication indicating he was seeking the opinion of the Commissioner of Lands and Survey and would confer with him about the new location of the Asylum. [11]

The Royal Commission of 1890 in a progress report strongly recommended that the Asylum be established at Cheltenham at the earliest opportunity but again the Government failed to act. [12] It was the announcement of a magnificent legacy to the Asylum by Mr J Hingston who died in England on March 8, 1902 at the age of 75 that galvanised the various parties and organizations back into action. Amongst the bequests to friends, relatives and other institutions Hingston left about £25,000 to the Benevolent Asylum to be applied to rebuilding the institution on a ground floor plan only. He saw, as a member of the Asylum’s committee, that the many floored and stair-cased building in North Melbourne very troublesome to the old and rheumaticky patients. [12] With access to a new source of funds the issue of moving the asylum to a site further out in the country was once again raised.

The Rev Alfred Caffin immediately responded to the bequest by writing to the Brighton Southern Cross to stress the value of the Cheltenham site. He pointed out it was located about twelve miles from the City and about two miles from South Brighton, Highett and Cheltenham railway stations and was situated on a pretty ridge commanding views of the bay and the Dandenong ranges. In addition, it possessed an excellent spring of water and soil of a light and friable character highly valued by amateur gardeners. Should the institution wish to expand beyond the reserve of about one hundred acres there was vacant land outside the boundaries of the reserve and the whole site was accessible to visitors. [13]

A few months later members of the Asylum Committee visited the proposed Cheltenham site and discussed with several councillors and shire officers questions related to drainage, reticulation and the construction of two roads to the site. [14] Previously they had made a request to the Minister of Lands for an additional twelve acres adjoining the 152 of the reserve to allow access to a spring. [15]

The councillors were very keen to have the institution at Cheltenham believing it would attract more residents to the area and assist in gaining a better train service, but they were concerned about road building costs. Cr Mills pointed out that the building of a road alongside the site would cost £300 and further expenditure would be entailed for gravelling the Moorabbin Road and Centre Dandenong Road; costs which the Council could not meet. However, he thought if the committee gave £ for £ the Council might see its way to assist in carrying out the work. [16]

The Asylum committee was very concerned about gaining access to the Cheltenham site. The contractor given the task of constructing the new building would need to convey large quantities of heavy materials to the site. Roads in their current state made this impossible. The committee was considering the building of a railway from the Cheltenham railway station to the site but they still needed roads and they were needed before the construction of the building commenced. This was the view that Mr Walker, the Asylum’s solicitor, put to the Shire Council. [17] Ultimately the Council gave approval for the construction of a two foot six inch gauge street railway as requested.

The engine, Nancy, on the street railway.

By March 1906 the architect C D’Ebro had submitted a scheme of the proposed buildings and the committee accepted it. They also authorised the clearing of 18 acres of land required for building purposes and immediate use. An officer from the Water Supply Department had reported positively on the presence of a plentiful supply of bore water on the site that would meet all the Asylum’s needs. He suggested a 50 foot shaft, 6 feet by 4 feet with two compartments should be sunk and an engine erected and two wells be sunk with windmills to supply water for the garden at a cost of £418. [18]

While preparations for the construction of the buildings had commenced the committee was concerned about the level of funding available to them. On September 16, 1907 a large deputation to the premier, Tommy Bent, presented the case for a special grant and in return was aggressively questioned by him on the financial position of the institution. Agreeing that there was £42,000 in the endowment fund Mr Walker pointed out that £20,000 was ‘tied up’. This did not impress the premier who indicated an Act of Parliament could free this money. He also thought the valuation of the land at North Melbourne was £40,000 and not £25,000 as Mr Walker indicated. When he was challenged by Mr Walker on his assessment he responded, “I think I know as much about land value as you do.” Mr Walker summarised the financial situation: £25,000 from the sale of land, £30,000 from the Hingston bequest, and £15,000 endowment money, a total of £70,000, and asked for a government grant to make up the balance to £100,000. Mr Bent agreed to place the matter before the Cabinet. [19]

A special general meeting of life-governors and subscribers was called the following month to consider whether the institution’s endowment funds should be appropriated to the building program. Attendance was poor. Before the meeting was adjourned committee members spoke in derogatory terms about the Premier who suggested the endowment fund should be used. One member described the situation as scandalous. [20]

It was some months later that the local newspaper was able to announce that the matter of the government grant had been resolved and work was to commence on the building of the new asylum. The architect was asked to prepare additional plans for a lodge, workshop and other out-buildings and to submit them to the committee so that fresh tender could be called for the construction work to proceed. [21] In March 1908 the committee of the Benevolent Asylum gave approval for the architect C A d’Ebro to call for tenders for the whole building program at Cheltenham. [22]

Preparing the ground for the building of the Benevolent Asylum at Cheltenham. Courtesy Betty Kuc.

The Asylum’s committee accepted the tender of Wadey and Company to build the new institution for a sum of £77,269 [23] and the early issue facing the company was how to get the material and men needed in the construction to the building site. The councillors of the Shire of Moorabbin were concerned about the impact of heavy usage on their fragile roads and the subsequent cost they would have to bear in their repair. In addition, new roads were required to give access to the site and old roads needed re-gravelling. Would the Asylum’s committee share the costs £ for £? The solution to this impasse was the building of a 2 ft 6in gauge light railway. [24] It was this railway that was used to transport guests to the site to witness the laying of the foundation stone in April 1909.

Laying the foundation stone, 1909.

The Governor of Victoria , Sir Thomas Carmichael, travelled by car from Macedon to lay the foundation stone of the new building in the presence of a large number of spectators. The laying of the stone was quickly dispensed with, allowing many of the guests to adjourn to the Recreation Hall, the first building on the site to be completed, for a fine luncheon. Unfortunately only 800 people could be accommodated in the hall so many, according to the report in the Moorabbin News, had to sip their coffee under most uncomfortable conditions

It was after the luncheon that Sir Thomas addressed 800 or more people saying he was glad to assist in such noble work as helping the poor of the State to spend their declining years in peace. [25] Then followed a series of toasts. Mr Murray, the Premier of the State, commented on the committee’s choice of location as a “rather out of the way position for the asylum – an impregnable fortress in the midst of a sandy desert.” But he did go on to say that a few years would bring about changes with only the addition of flowers and vegetable gardens to make it a beauty spot. [26] Cr Ferdinando, speaking on behalf of the Moorabbin Council, agreed with the Premier’s remarks about remoteness but suggested the remedy was in his hands and assured him any money he cared to allocate to the council to improve the roads would be spent judiciously for the benefit of the community. [27]

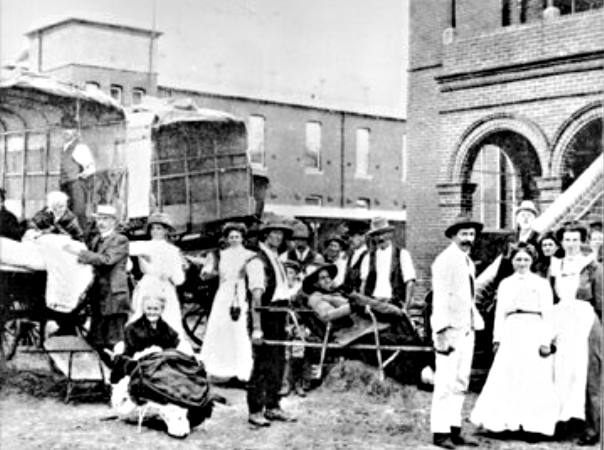

It was almost two years after the laying of the foundation stone that the transfer of patients from North Melbourne to Cheltenham began. The logistics for such an occasion given the distance, the condition of many patients and the available transport were immense. Added to this were the emotional feelings held by many patients leaving the gloomy but friendly environment they had known for many years, while others were looking forward to more pleasant accommodation ‘by the sea’. Some were so old and feeble they took no interest in what was a momentous occasion in the history of the institution. [28]

According to the Age report, the asylum authorities expected some inmates to refuse to go to Cheltenham and instead seek shelter with friends, but there were few such cases. Most recognized the asylum provided them with security and contact with friends.

The move was completed in stages with the first group to leave being one hundred and twenty five inmates from the women’s invalid wards. It took five hours to load the furniture vans and three days to move all the residents from their old North Melbourne home to Cheltenham. In total 513 were transferred and of that number 313 were bed ridden. [29]

Patients arriving at the new Melbourne Benevolent Asylum, 1911. Courtesy Kingston Centre.

When the new arrivals reached the new Cheltenham buildings they were greeted by ladies from the local community. A team of women lead by Mesdames Allnutt and Penny provided refreshments. Inmates then adjourned to their beds in the new facility covering four acres in the middle of a block of land of 144 acres. The concert hall, wards and kitchen were furnished, but the gardens and artificial lakes remained to be completed. [30]

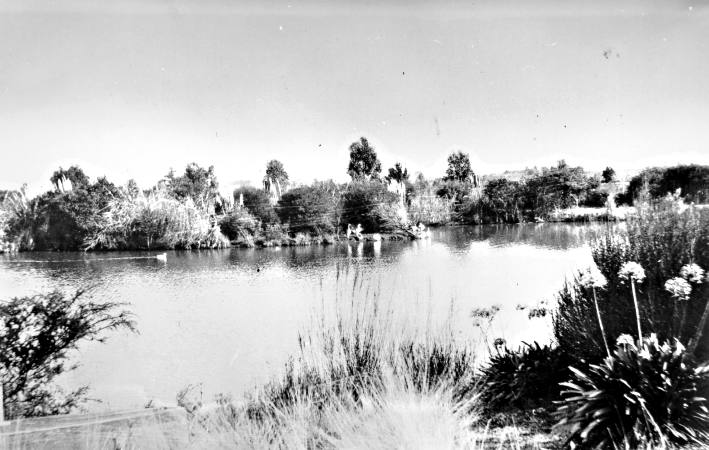

Ornamental lake at Benevolent Asylum. Courtesy Len Allnutt.

By the beginning of 1920, almost nine years later, Ketteringham was writing in the Moorabbin News lavishing prolific praise on the institution now well established at Cheltenham with its gardens and lake. He described the artificial lake with its wild duck, the neatly trimmed lawns, variegated flowers and ornamental trees which the Premier envisaged at the laying of the foundation stone in a desert like environment. [31] Ketteringham also wrote of the spacious, well ventilated wards where the beds were spotlessly clean. Bathing facilities were considered to be unequalled with a plentiful supply of hot and cold water always being available. He noted that every inmate was compelled to bath at least once a week. The dining room he thought surpassed anything he had seen in other institutions for its cheery brightness and tables without blemish. The waifs, strays and physically decadent inmates, with senile decay written upon their profiles, were nevertheless, he thought, contentedly waiting for their death. [32]

The asylum was renamed the Kingston Centre in October 21, 1970 and the focus of its service dramatically changed. No longer was its prime attention given to catering for the long-term stay of the disabled, blind, infirm and elderly patients. Its more recent history has seen services focussed on rehabilitation but that is another story.

Kingston Centre from the air, 2002. Courtesy Mirvac.

Footnotes

- Kehoe, M., The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum: Hotham’s Premier Building. , 1998, page 14.

- The Argus, September 6, 1849.

- One Hundreds and Fourtieth Annual Report – 1989-1990.

- Kehoe, M., op. cit. page 19.

- Kehoe, M., op. cit. page 58.

- One Hundred and Fortieth Annual Report 1989-1990.

- Kehoe, M., op. cit. page 62.

- The Age, March 4, 1887.

- Brighton Southern Cross, March 12, 1887.

- The Age, March 18, 1887.

- The Age, March 25, 1887.[12] Kehoe, M., op. cit. page 64.

- The Argus, March 14, 1902.

- Brighton Southern Cross, March 22, 1902.

- Moorabbin News, August 19, 1905.

- Moorabbin News, May 6, 1905.

- Moorabbin News, August 26, 1905.

- Moorabbin News, March 3, 1906 & Whitehead, G., Street Train to the Benevolent Asylum, Kingston Historical Website http://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au

- Moorabbin News, March 17, 1906.

- Moorabbin News, September 21, 1907.

- Moorabbin News, November 9, 1907.

- Moorabbin News, February 1, 1908.

- Moorabbin News, March 14, 1908.

- Brighton Southern Cross May 9, 1908.

- see Whitehead, G., Street Train to the Benevolent Asylum, Kingston Historical Website http://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au

- Brighton Southern Cross April 3, 1909.

- Moorabbin News April 3, 1909.

- Brighton Southern Cross, April 3, 1909.

- Weekly Times, March 27, 1911.

- Kingston Centre, One Hundred and Fortieth Annual Report –1989-1990.

- The Age March 28, 1911.

- The Age January 24, 1920.

- Moorabbin News, January 24, 1920.