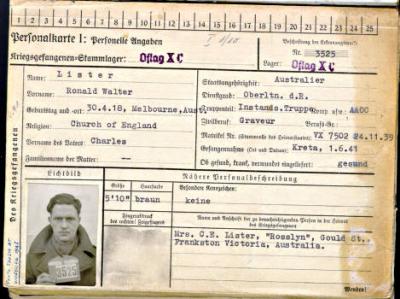

Ron Lister’s identification card when a prisoner-of-war in Germany.

‘Friendly Fire’ Kills Many Men

With the outbreak of the Second World War , Ron Lister of Parkdale enlisted with several friends in the Australian Army and saw service in the Middle East and Greece. While he was in Crete he was captured by the Germans and ultimately imprisoned with other Allied officers at Eichstatt in Germany. During his incarceration he continued to keep a diary and later used it to write his story. Some aspects of this experience were recalled in an article on this website entitled “Prisoner of War”1 and in one paragraph Lister mentioned the time, only days before the end of the war, when an American Mustang strafed the prisoners. They were being moved to another camp by their guards ahead of the advancing American forces commanded by General Patton. At the time they were slowly progressing along the road to a camp at Moosburg north of Munich. As a result of the air attack fifteen men died and more than fifty were wounded.

This latter aspect of Lister’s story was seized upon by Melissa Eisdell of Pimlico in England when she was researching the death of her mother’s uncle, Ben Jickling. He was one of the officers who died in this airborne attack. A British captain, Jickling had been captured at Dunkirk. Melissa wanted to know more about the air attack and contacted Ron Lister to see if he had more information.

Lister said he did not personally know Ben Jickling but he had vivid memories of the attack. There were about 3000 prisoners at Eickstatt and only about one hundred Australians. But, he recalled, a Canadian friend, captured in the Dieppe Raid had put together a collection of reminiscences from fellow prisoners in a book entitled “The Day the War Ended”. In the book was an article written by Major Elliott Viney about the ‘plane shoot up” and there Ben Jickling was named amongst the dead.

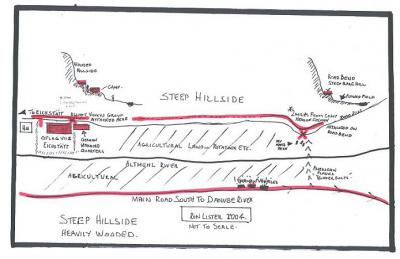

Ron Lister said the prisoners, as they moved from Eichstatt, were in good spirits because only the “dumbest German would not realise that the End was only days away.” The last group had left the camp and all the prisoners were moving along a winding road in the valley which hugged a steepish hillside. They were heading for a bridge across a river to join the main road where a convoy of five trucks were waiting before approaching Eichstatt. A single American Mustang plane appeared and flew up the valley and waggled its wings as it passed over the column of prisoners several times. Lister recalled that they waved and shouted while pointing to the German trucks about half a mile away on the other side of the valley. No effort was made to indicate to the pilot that the column of men were prisoners of war. Shortly after a group of ten Thunderbolt planes returned and bombed the convoy of vehicles setting them alight and scattering their crews. The observers of this conflict were delighted, yelling and slapping each other on the back as they saw the havoc and destruction caused by the attack and watched the planes gain height and regroup. It was moments later that the men realised with some horror that they were the next target.

Elliott Viney wrote that the planes came diving across the column machine gunning as they went. The men had difficulty scattering because of the steep hillside to their left and a fence on their right. Many took shelter in a ditch while others made it to an open ploughed field next to the river. Lister recalled “We watched the dirt being thrown up in twin tracks as the planes attacked. While the planes had used their bombs to attack the convoy the assault on the column of men was still devastating because a burst from the machine guns could slice a man in half.”

The column of men moved back into the camp carrying the wounded. Viney said he helped carry Ben Jickling who had been shot in the shoulder, adding, “His arm fell and a great stream of blood came over me. He was already dead then.” Viney named other friends who died or were injured. Donald Price was shot through the heart, Humphrey Marriott was shot through the spine and Johnny Cousens had his leg almost shot off. “The machine guns made ghastly wounds,” was his comment.

How could such a tragedy occur? Why was it that men only a short time from freedom should be killed by ‘friendly fire’? Lister wrote that later they were told the Allied air force had been instructed to attack anything moving on the roads and that Hungarian troops, who wore khaki, were in the area. To exacerbate the situation the prisoners were not able to give any visual identification as to who they were to the pilots of the aircraft. There had been some early attempts to lay out some sort of signs but were stopped by the guards. Later, Lister said a white sheet was torn into strips which were sown onto a red hospital blanket and laid out in the open near where they were accommodated. To this Swiss flag were added the letters P.O.W. made from the sheeting.

A few days later when the prisoners were once again on the move, walking at night and seeking shelter during the day, Lister reported the incident when a member of his company aided a farmer’s wife. Ron Lister and his friend Frank Evans together with several others had taken on the responsibilities of running the first aid post with their limited supplies of Aspirin, bandages, Elastoplast and antiseptic tablets of acriflavine to dissolve in water. They had been trained in first aid procedures by a Sydney surgeon to enable them to take on the role. The farmer’s wife, where they were billeted during the day, had a boil on her backside and sought the assistance of ‘Doctor’ Evans to relieve the pain. He did this successfully and was rewarded with some very welcome food. This must have been a humorous interlude during a very tense time when all participants were wondering whether they would make it home. It was at mid morning of that day that bombers, part of the biggest daylight raid that occurred during the Second World War, passed overhead. According to Ron Lister the flights of bombers seemed to go on for hours. Fortunately, Lister said, “they were not interested in them but he personally didn’t take any chances and hid out amid a large pile of firewood logs.”

The prisoners of war from Eichstatt reached their destination of Moosbury without further incidents from ‘friendly fire’ and eight days later were given their freedom by the advancing troops of Patton’s 7th Army. Victory in Europe was spent at Rheims in France. The following day they were transported to England where their physical condition was checked and new uniforms issued before they were given leave and transported home. For some members of the Eichstatt-Moosbury march this was the first time in four or more years that they had seen their wives, children and relatives.

- 1. https://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au/ Article Ref 33.